Image courtesy of wikimedia.org

Ithaca is a town that, when I was in graduate school at Cornell University in the late 1990s, had a population of 30,000. Whatever you have heard of Ithaca’s scenery is no exaggeration. Every season, except winter, is postcard picturesque. Once snow falls, a shadow envelops the place, the sky gray as if volcanic ash were rolling forth. Ithaca doesn’t offer much for diversion nor is an escape easy; to get to Manhattan requires a five-hour bus ride. Cornell is its pulse. Either you fit in or you don’t. Social activities from parties to dining occur no further than half a mile beyond the campus, and nearly all cater to undergraduate students. One gay/lesbian club existed back then, the Common Ground, which was four miles away. This is why my friend, Jason, said that had he and I met amid the bustle of San Francisco or Manhattan, we would not have moved on after one night, but because we were stuck in the boonies, a friendship developed, fate’s way of joining two souls.

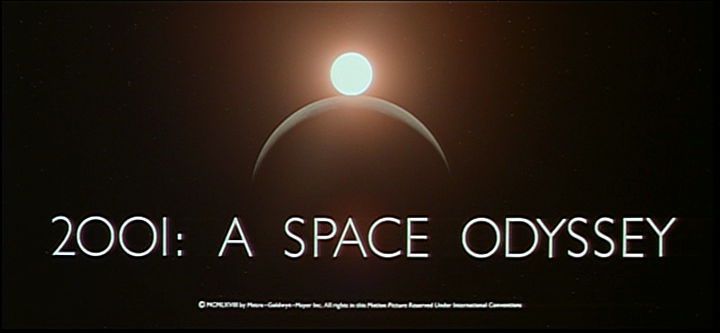

So it is with Hermie (Gary Grimes) and Dorothy (Jennifer O’Neill) – he, a 15-year-old bewildered by the riddle of love and sex; she, a war-bride in her early twenties – in Nantucket Island, off the coast of Cape Cod, awash with the tinctures of a soft watercolor. They are as opposite a pair as can be, yet they are. It is the “Summer of ’42” (1971). Dorothy lives alone and far from neighbors, in a wood cottage atop a dune that overlooks the sea. Hermie spends his days with pals Oscy (Jerry Houser) and Benjie (Oliver Conant), frolicking on the beach and discussing schemes to feel out a girl’s breasts. Hermie and Dorothy meet when the boy offers to carry her groceries. She accepts since she’s got so many that items are falling to the ground. She should have brought her cart, she says, and we question why she didn’t. It’s a long stretch from the market to the cottage. Even Hermie is panting by the end of the journey. We also question why she’s in Nantucket, how she manages to vanish the morning after their emotional interlude at the movie’s climax, and what becomes of the cottage.

Image courtesy of ebsqart.com

Or maybe that’s just me. From the start, Dorothy is a mystery, a dream girl who transcends reason. She’s an angel of no origin or destination, in the present for the sole purpose of acting a part in this crucial chapter of Hermie’s life. If there is a mantra for love, Hermie recites it in voiceover as a middle-aged man still in awe of this unforgettable woman:

Nothing from that first day I saw her, and no one that has happened to me since, has ever been as frightening and as confusing, for no person I’ve ever known has ever done more to make me feel more sure, more insecure, more important, and less significant.

Had Dorothy and Hermie met anywhere else, “Summer of ‘42” would have been another uneventful summer, Herman Raucher would not have written the memoir on which the film is based, and I would not be writing about Jason. Not to say that Jason and I became googly-eyed lovers, but we did become fantastic friends. Our relationship started at the Common Ground. He introduced himself and chatted me up one night, then later asked me if I needed a lift home, at which I responded, “No, thanks. I’m working on the guy in the orange shirt.” When I got back to my place early dawn, a voicemail message was on my phone machine; Jason had looked up my number in the student directory. He was extending an invitation to dinner. It so happened he lived directly across Ithaca Commons, a hundred steps between us, so that for the two years that followed, he would on occasion have a view of me in my underwear and I of him at his desk. It’s a free meal, I thought and nothing else.

Image courtesy of pix2.epodunk.com

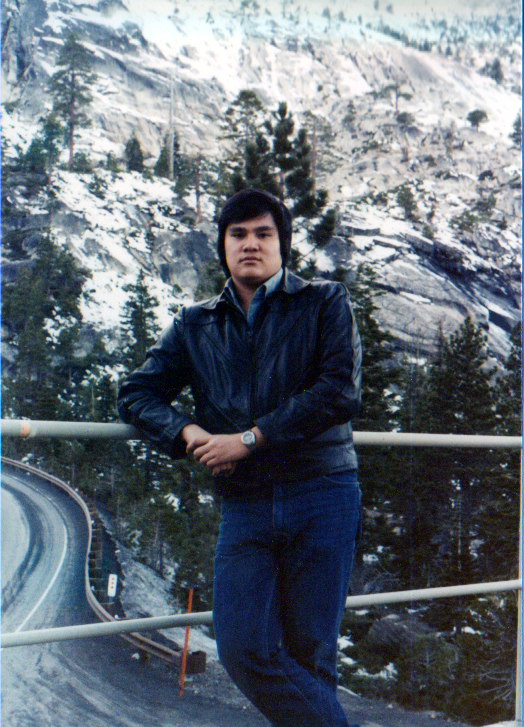

Nights later, I walked up the stairs of a brick box of a building to Jason’s front door. He greeted me with grimy fingertips (from hours spent at the kitchen chopping board, I presumed) and a smile seen only in tourism ads (he was earning his masters at the hotel school). With nose, feet, and jaw as sizeable as his smile, brown hair almost black, and a complexion the shade of sea drenched sand, Jason seemed more a child of nature than a native urbanite (Jewish New Yorker).

I did not like Jason. The pad thai was delicious. The wine added a fine touch. The conversation… smart guy, he is, but in the course of our meal, combative. He had lived in Indonesia, where he trekked across the Borneo jungle and opened a diving center, operated on an injured hand during a mountain climbing accident and traveled through Asia – all this by the age of 26. A cockiness was evident so that whatever I told him of the Philippines, he contested with a smug smile. I folded my arms in fury. He laughed. I wanted to walk out, but being tipsy, I huffed my way to an armchair instead. He followed, pinned me to my seat, and that was that.

Image courtesy of dianalewis.ca

The morning after, he asked if I was always that easy. I don’t remember my response. It could have been a snarky yes or I could have said that putting out was frugal and less strenuous than taking a trip to the drug store to buy a card, writing a thank you note, placing the card in an envelope, sealing it, falling in line at the post office to purchase a stamp, and mailing the damn thing. Jason was right. Had the two of us been in a metropolis, our meeting at a club would have led to naught. As he has told me, I was an “asshole” for brushing him off the way I did. Our stars had other plans, however. The world needs tales like Jason’s and mine, like Hermie’s and Dorothy’s. It’s precisely Jason’s commodious knowledge that I came to love about the guy. If he didn’t have an answer to a question, he never said “I don’t know;” rather, “this is how you can find out.”

When Hermie visits Dorothy on the night she receives a telegram of bad tidings, neither of them planned on what was to happen next. For Hermie, it was such a remote possibility that he doubtfully entertained the mere fantasy of it. For Dorothy, he’s a child. Nevertheless, isolation brings two together, and a connection is never more potent than in a moment of grief and compassion. She’s lonely. He’s at the right place, at the right time. The affection he shoulders for her isn’t a crush. The boy loves her. It’s meant to happen.

For our sake, Hermie grows up to tell us how this experience carries a generational significance. Never shortchange love. Never underestimate chance. With good intentions, a bond can forge with the most unlikely person in the most unlikely place.

Image courtesy of obviousmag.org

.jpg)