Image courtesy of whicdn.com

Laurence Olivier once said of Vivien Leigh that if not for her brilliance as a thespian, then he would never have fallen in love with her. She was ravishing, to be sure, a glacial beauty with neither a hair out of place nor sweat on her brow no matter the depravity of the character she played, which made her ability to convey torment all the more uncanny. This was no easy feat. So comely was she that she had to summon her inner demons in order for others to look past the surface. One doubter she won over was Elia Kazan. During the casting of “A Streetcar Named Desire” (1951), the director was skeptical of Leigh in the role of Blanche Dubois. (http://www.rafsy.com/films-1920s-1950s/a-streetcar-named-desire-forever-young/) He considered Leigh an actress of “small talent,” an opinion he would recant the instant the camera rolled. “She’d have crawled over broken glass if she thought it would help her performance,” he said. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vivien_Leigh)

Talent accounts for a lot, and not just in the professional arena, but also in love. Olivier’s admission of his choice of a second wife would impact me as a haunting refrain ever since I first learned of it 25 years ago. As I am in a creative field, talent surrounds me. Katharine, a girl I knew while on a writing fellowship at Cornell University, speculated that myriad romances must have blossomed through the centuries on account of a reader’s infatuation with an author’s words. Seems logical. Authors must write fabulous love letters, and who of us wouldn’t want to be the recipient of an epistle where we are the source of rapturous prose? Gustave Flaubert must have seen the form of Emma Bovary in his paramour, the poet Louise Colet, when he lavished her with this:

Image courtesy of atriodeigentili.it

“I will cover you with love when next I see you, with caresses, with ecstasy. I want to gorge you with all the joys of the flesh so that you faint and die. I want you to be amazed by me and to confess to yourself that you had never even dreamed of such transports… When you are old, I want you to recall those few hours. I want your dry bones to quiver with joy when you think of me.”

To be the template for one of literature’s most revered creations is the highest flattery. A colleague at the writing program who had feelings for me expressed regret when, one day, I missed his reading of a story. “If only you could have heard me,” he said, hoping that his oratorical talent would have caressed my ears and stirred my own feelings beyond the platonic. Even if it had, whatever tenderness that might have budded between us could just as swiftly have wilted, for we artists are selfish and envious. Place us with six other people in one workshop that meets weekly, critiquing each other’s manuscripts to the point of lashing out insults, and you’ve got a brew that simmers with competition. One falls to the perimeter. The other basks in the limelight.

Cinema has quite a few tales about such couplings. Kenneth Halliwell (Alfred Molina) in “Prick Up Your Ears” (1987) axes lover, playwright Joe Orton (Gary Oldman), for raking in all the plaudits. In a film named after her, “Camille Claudel” (1988), who was protégé and mistress (Isabelle Adjani) to August Renoir (Gerard Depardieu) and who herself was an exceptional sculptress, is confined to a psycho ward as the world lauds her mentor as a master. “Sylvia” (2003) portrays Sylvia Plath (Gwyneth Paltrow) as a poet whose emotional paralysis under the weight of the success of husband Ted Hughes (Daniel Craig) drives her to inhale gasoline in her sleep.

Image courtesy of wordpress.com

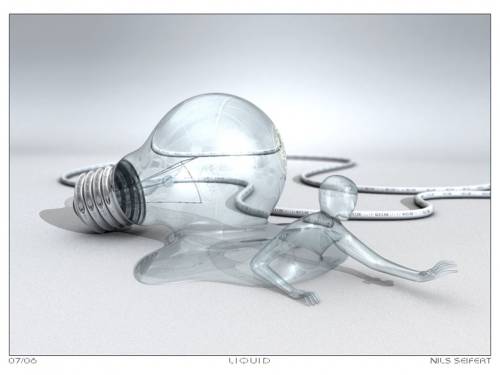

Art is a Greek tragedy. Even without the drama of murder, institutionalization, or suicide, we are lamed when it gives us the short end of the stick. Our talent accounts for nothing. Life is meaningless. In this, history repeats itself every decade. “Begin Again” (2013) is a film of today with the pathos that has made some of our artist couples of yesterday prime subjects for the big screen. Gretta (Keira Knightley) is musically gifted. She strums the guitar to lyrics of her own musing, her voice a whisper more than a bellow – ethereal, sensuous. Nobody at the bar hears her. Her own boyfriend Dave (Adam Levine) is deaf to her, himself a singer-song writer to whom she is both muse and critic instrumental in elevating his compositions that much closer to glory. He makes it, a record deal and a world tour the answer to his dreams, yet not once does he acknowledge the woman who has placed her own talent secondary to his.

Although “Begin Again” is fiction, it is rooted in reality. At Cornell, Katharine and I worked together during our first year as editorial assistants to Epoch, a literary journal the English department publishes. One of our instructors had been a Stanford University Stegner fellow, an honor bestowed upon the most promising of writers. (The Stegner roster includes Ken Kesey, Raymond Carver, and Molly Antopol). She had come out with a collection of stories to rave reviews, one of which I had read in creative writing 101 during my freshman year at Tufts University. She was also the romantic partner of the journal’s editor-in-chief, a man. Katharine would wonder why our instructor’s initial success had not led to further accolades, until she had a conversation with her mother, who said, “She doesn’t want to lose him.” Stated another way: for one to be a star, one must make a choice between fame and love.

Vaudevillian, Fanny Brice, was well aware of this sacrifice. “Funny Girl” (1968), which features Barbra Streisand as the comedian, depicts her marital collapse to Nick Arnstein (Omar Sharif), a man about town who introduces her to the good life when she is yet a nobody slaving to have her name spelled out in bright lights. One hitch: Arnstein is a gambler and a crook. Guilty of embezzlement, he is imprisoned and his fortune dwindles. Brice, now a star, offers financial rescue, which his masculine pride refuses. Neither can he remain affiliated as husband to a woman who eclipses him in status.

Image courtesy of fantasyartdesign.com

Luckily for Gretta in “Begin Again,” her fate isn’t dismal. Someone in the crowd is actually taken by her music, and he happens to be a somebody. He is Dan Mulligan (Mark Ruffalo), a record producer. Hold on, though. The days ahead of Gretta aren’t as simple as this plot turn implies. Heartbreak is never so quickly resolved. In an epiphanic moment, Gretta watches in the sideline as Dave onstage performs to the orgasmic screams of the audience. He glances at her and smiles. She smiles back. Amid the percussion of drums and electric guitars and the orgy of arms that reach out to Dave from a pit of gyrating bodies, an invisible current welds the two together. They have been through so much. He has come so far. But like all sparks, the current lasts through one verse of a song.

Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh were able to share the limelight, the wattage of their combined talents so refulgent that it garnered them ovations and awards. Alas, the big bang that they were resulted in a dark void. The genius of creativity triggered her mental breakdown. He left her for Joan Plowright, herself a fine actress, though one denuded of the trappings of celebrity. Psychological and health issues notwithstanding, Leigh continued to make movies and to appear in the theater. The public’s adoration was all she had left.

Image courtesy of worldnow.com

We all need someone. Life is too full of quicksand for us to free ourselves from the guck on our own. And yet, when a burning within to show the world our ability for greatness flames our egos, we jump into the fire. Either we disintegrate to ashes, scattered in the wind and forgotten, or we blaze into immortality. We accept the risk, regardless of the expense on the one person who matters most, for we more fear domestic complacency, the realm of the ordinary.

.jpg)