Image courtesy of slantmagazine.com

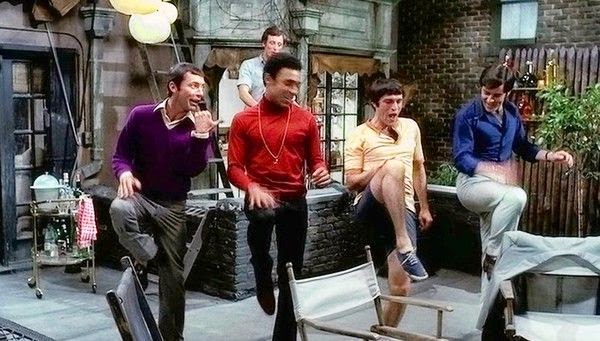

“The Boys in the Band” (1970) is a groundbreaking film that in the 45 years since its release has fallen out of favor with many gay men. “Self-loathing” is the term frequently associated with it. The “boys” in the title references a group of homosexual male friends gathered at a birthday celebration that devolves into an infernal mess of insecurities and childhood traumas. What starts out as a line dance on a roof top terrace turns into a circle of truth in which each guest is dared to phone the person he loves, even at the risk of humiliation due to the possibility that the person at the other end of the line could be a heterosexual man. Name callings ricochet like bullets. Celebrant Harold (Leonard Frey) refers to himself as an “ugly, pock-marked Jew fairy” then quickly turns around and accuses host Michael (Kenneth Nelson) of abhorring his predilection for men. Michael calls guest Donald (Frederick Combs) a “card carrying cunt.” Donald certainly must have said something in retaliation for such a disgusting insult. But at this point, the hate is so overflowing that every antagonism and defensive outburst jumble together the way garbage does on a barge. These boys are self-loathing, indeed. May I add angry, bitter, bitchy, nasty, and mean. I will also be so brazen as to declare that these vices are precisely what warrant the film its virtue. Although we may not entirely like the manner these guests behave and treat each other, the emotional turmoil they find themselves in speaks the truth of what I myself have experienced as a gay man for the past 25 years.

John Keats said a mighty long time ago that “beauty is truth, truth beauty – that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” The poet could not have predicted the can of worms the liberation movements of the mid-20th century would open, in particular the movement that would build the foundation of the community of which I am now a member in San Francisco. Truth is important, I agree, and it can be beautiful. Truth is enlightenment, after all. But it can also be ugly. Wisdom never comes without pain, and I mean the lacerating kind of pain that makes our hearts bleed.

Image courtesy of tse4.mm.bing.net

My initial viewing of “The Boys in the Band” was an accident. I was 15 years old and living in the Philippines. While my parents were hosting a party, I was in their room, flipping through the TV remote when I chanced upon a man as he waited on a curbside, casserole in hand, for the pedestrian light to turn green. Chin raised in impudence, eyes wide as a toad’s, he was hoity-toity towards a woman dressed in a moo-moo and who was acting likewise towards him. Emory (Cliff Gorman) was the first gay movie character I ever saw and he was in the Big Apple, a city I considered a Valhalla on earth by virtue of my sister, who was attending college at Columbia University. Imagine yourself as me – a Hollywood-struck Filipino boy with a fashion plate sister in America’s most revered metropolis. On school breaks, she would regale me with accounts of clubs, parties, and shopping, her eyes lit as if she were a princess who had been granted a kingdom. She was, in a way. Her closest friend at the time was Robin Givens (before Mike Tyson entered the picture). They once got to ride a fire truck because a group of firemen, good Samaritans that they are, were concerned over the safety of a pair of beautiful teen girls who appeared dazed and lost in a rough neighborhood. So on went the siren, and armored in work gear of helmets, boots, and shields, these flame killers chauffeured my sister and Robin to the party the two had planned on reaching by traversing Central Park. At night. Who else has a story like that to tell? Only my sister.

That was where my head was at when the festivity on TV started – an adventure in New York free of parental guidance. In this sense, you can say that I didn’t see “The Boys in the Band” for what it really is. What 15-year-old possesses such a deep level of astuteness anyway? All I was aware of was the thrill I felt in witnessing my tribesmen pour their guts out over what an experience it is to grow up a sissy. Sure, they were as frightened as a bunch of cornered cats. Nevertheless, they divulged secrets; they empathized with each other; and they weren’t alone. For that instant, I was no longer alone either.

Image courtesy of 3.bp.blogspot.com

Life decisions brought me to San Francisco instead of to New York in 1990 at the age of 23. Revelry was in the air. I formed my first group of gay friends. We had parties to get drunk at every weekend and clubs every night to dance in till dawn. We were young and thus we managed at work the next day with the energy an eight-hour sleep provides. But I also quickly realized that for all the hype of solidarity and pride, the gay community was… and continues to be… fractured. Back then, bars existed that were designated venues for specific races: N-Touch for Asians; Esta Noche for Latinos; the Pendulum for blacks. Labels were created to identify those who fixated on a race: Rice Queen, Bean Queen, and Chocolate (sometimes Dinge) Queen. Meanwhile, white gay men stuck together in their own bars from the Castro to the South of Market and all the way up to Pacific Heights.

Image courtesy of gstatic.com

In the age of online hook-ups, the racial segregation remains apparent. Personal ads state “not into Asians,” “not into blacks,” and “white only.” Discrimination also extends to body types and mannerisms as manifested by the pronouncements of “no fats” and “no fems” and the ever endless search for “only straight acting guys.” We even have gay porn stars who deny any homosexual inclination whatsoever, as if being gay was shameful, and who insist instead that they are straight blokes in it for the money.

None of this exemplifies love and acceptance. It’s heart wrenching. We gay men are, to a large degree, guilty of the self-loathing of which we accuse Harold and his band of buddies. And with the alpha male archetype of muscled physiques dominating the gay media, it’s apparent that all the brawn we’re encouraged to hide our bodies beneath is an armor to protect ourselves against something that’s disturbing and deep-rooted in our psyche.

Michael makes a tear-soaked bid: “If we can just learn not to hate ourselves.” Kenneth Nelson might not have been acting when he said this. He was gay as were many of the other cast members, and they would all fall victim to AIDS. We can only assume that the issues of aging, body image, and bullying that saturate the film hit close to home for the performers. As for me, I thank writer Mart Crowley and director William Friedkin for “The Boys in the Band.” Had Hollywood provided me at 15 a glimpse of my future the gay romantic comedies of today that feature pretty white boys falling in love and living happily ever after, then… God, help me… I really would have been screwed.

.jpg)

Image courtesy of 2.bp.blogspot.com

Great essay. I really liked this. However, as someone who saw it around 1980, when I was in college at Northwestern, I must say the film never was in favor. It caused the same anxiety one felt about drag queens back in those days. I always thought it was the gay version of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. I’ve got to watch boys in the band again soon. Thanks for the inspiration. It really was the first time seeing gay men on screen, and I too was totally in awe of NYC! It seemed like Oz…with gay men. Quite a fluke I ended up in SF.