Image courtesy of proxy.duckduckgo.com

Ms. Aimee was not typical of the ladies of her generation who resided in this part of San Francisco. Nearly 20 years ago, when I was new to the city, wide eyed as any college graduate at the certainty of a glorious future, the ladies donned sable to attend Sunday mass and organized charity events over afternoon tea. Ms. Aimee’s attire never changed through the years that we happened to share the elevator or chanced upon each other in the lobby: a prairie skirt paired with sandals and a hand-knitted cardigan. The one common factor Ms. Aimee shared with the ladies was gray hair tinged blue under a certain light.

“Where we are, it’s unique among all the places in the world,” Ms. Aimee said on the day she invited me for milk and apple pie. This in reference more to the neighborhood than to its high society denizens.

Nob Hill is famous for the Brocklebank Apartments, a towering edifice the cream of old paper and with two residential wings perpendicular to each other like pages to an open book. Cinema has immortalized the apartments, most notably in “Vertigo.” You know the scene. Detective Scott Ferguson is parked along a sidewalk, restless as a rooster as he spies on Madeleine to appear past guarded doors, from the shadow of an awning, and is at once wonderstruck when she does, pristine in magnolia white coat and gloves midnight black that accentuate the delicacy of her hands. The scene is one for the ages. No matter your generation, you are stunned. Who of us hasn’t felt a caress of the heart at the mere sight of a beloved?

Other landmarks untouched by time merit Nob Hill its romantic aura. The Fairmont Hotel is resplendent with the opulence of the Gilded Age – pilasters and cornices and world flags at full mast lined on a balustrade that crowns the entryway. It is here where Tony Bennett first sang “I Left My Heart in San Francisco.” Grace Cathedral is a replica of the Notre-Dame but never more so than on foggy nights, when mist renders it the appearance of an image in a Monet.

The Brocklebank and the Fairmont both stand on Mason Street, towards the east of the Bay Area. Directly across to the west on Taylor Street, face-to-face with the hotel, is the cathedral. In between them: the Flood Mansion, a box-like structure of columns and floor-to-ceiling windows (the hue of chocolate milk, the mansion is the only grand home to survive the 1906 fire) and Huntington Park, with its center piece a sculpture quartet of male water spirits, each one affixed on marble sea shells as they hold aloft a fountain basin. California Street constitutes the south border of the park, and Sacramento Street the north, and right in the middle of Sacramento, in the tallest building on the block, is where I live.

Image courtesy of www.i5.fnp.ae

I occupy the balcony unit on the west wing of the 5th floor, right above Ms. Aimee. There’s a reason the plant pots that bookend the balcony are empty. They are only filled when I’ve got family visiting, usually my mother. She adores flora, the burst of foliage decking this corner and that, as if domestic serenity were as infinite as nature. She buys my stock of toilet paper, detergent, disposable razors, and shaving cream, and she has me invert her mattress upon her departure so that, on her next yearly visit, the end where her head had lain would then accommodate her feet. (My mother read somewhere that this mattress flip-flop prevents sagging on each end from the weight of the sleeper’s cranium.) Within a month of her gone, the plants wilt, as do the white orchids in the dining room and the geraniums on a marble top strategically positioned in front of the balcony for the sun to highlight their lavender sheen. “Once a week,” my mother has pestered about watering the flowers and greens. “That’s not much, just a bit of love.” But a week goes by so quickly that I forget, and when I do remember, I drown them with too much love.

I’m somewhat of a free boarder in this fancy dwelling. It belongs to my parents, purchased as a home away from home. Their permanent address remains in the city where I was born and raised, where cricket chirps would lull me to sleep as a child and radio stations air Christmas carols starting September, where after wrestling practice at the recreational center, I used to imagine I was taking dance instead as girls to a ballet class would slip into their pointe shoes. The city is a far away enough place to justify the long stays of family, which for my father and older brother and sister can be two weeks, while up to six weeks for my mother, although this past year she didn’t come at all due to knee arthritis.

My father is a septuagenarian, which my mother will soon be. I myself am in the early phase of my middle years. That I maintain an active lifestyle of hikes and gym workouts keeps me youthful. Nevertheless, aging becomes an ever more present reality because I witness it in the doormen and in the neighbors, many of who have passed on, others of whom I realized one day, as you would an afterthought, that I haven’t seen in a while and doubtfully ever will.

“She was like you, all sprightly and on the go,” Lincoln, the head doorman, once said of Ms. Aimee. “Now she walks with a stoop.”

Lincoln himself is an institution. He has been with the building since its first tenants. (That would be 52 years ago.) The same age as my father, he remains on the tip of his toes, his smile the exuberance of a marionette. The thinning of his hair from a bush of black curls to white bristles is the predominant sign of his advanced years. Other doormen younger than Lincoln have not matched his longevity neither in life nor at the building. One died of a heart attack while lifting a suitcase. The loss took a toll on his brother. A dapper figure when I moved in, the brother would pace the lobby with the vigilance of a sentinel. He retired shortly after the tragedy, heartbroken and hunched with a walking cane. There was the doorman who kept failing the board exam to be a pharmacist. Now jowly and hollow in the eyes, he was merry when I ran into him on the bus recently in his reminiscences of his days at the building and somewhat melancholic, as well. Then there was the doorman who was fired over a fist fight with Lincoln. He became a flight attendant and… as doorman gossip has it… has undergone a nip and tuck.

Of Ms. Aimee’s hair, Lincoln said, “I don’t remember anymore what color it was. It seems to have been blue since forever.”

And blue her hair was till the end. Ms. Aimee died last month. She was 85, bedridden and quiet, as quiet as a forlorn lover, as a nightingale silenced by an arrow pierce to the heart. I stress her reticence, for it was noise that brought us together for a chat on that one and only occasion a year ago, noise of which she was the culprit. You see, she had just become a widow. Unexpectedly.

Image courtesy of i.ebayimg.com

Talk about sprightly, that her husband certainly had been. I first met him in the elevator within a week of having moved into the building. I was so young that he mistook me, pizza box in hand, for a delivery boy. “So the tenant on the fifth prefers food ordered in, eh,” he said. “Not really,” I said then shook his hand. He spoke with a nasal voice and enunciated his words as if his mouth were filled with marbles (the way James Stewart spoke, come to think of it), and where Ms. Aimee was rustic in dress, he was juvenile. Whatever the weather, he wore shorts, and not long grandpa shorts, either, but short shorts with the hem as high as the pelvis. I soon learned that such clothing was conducive to his lifestyle. He cycled weekly. I was impressed. Due to the hilliness of the city, a bicycle could be a strain on the body. Not for him. Our building is perched on the tallest peak in the downtown area, yet with what energy he would pedal up and down the slopes, his small boyish frame bent over the handles, his muscular legs in speedy circular motion. The one article of clothing that kept him warm on cool days was a baseball jacket embellished with pins championing a miscellany of causes: Save the Whales, a peace sign, a smiley face, the LGBTQ rainbow, Think Green, Stop Animal Cruelty… Such a model of health and senior robustness was he that I had pegged him to be a candidate someday for the oldest person alive. Alas, no. And that was when Ms. Aimee started turning on her TV to near full volume and keeping it on through the wee hours of the morning.

As a result, Ms. Aimee and I were in conflict with each other. I would phone the doorman so that he could phone Ms. Aimee to inform her that she was causing a disturbance. She would lower the volume but not always. A few times, at twilight, I was so fed up that I would ring her buzzer.

To give you a sense of my experience standing at Ms. Aimee’s door, allow me to explain the layout of a story to our building. Two units occupy a story, one on the west wing and one on the east; thus, the elevator has two doors, one for each unit. As you exit the elevator, you step directly into a foyer with a single unit door before you. Some residents have chairs, mirrors, paintings, and rugs furnishing their foyer. The floor to Ms. Aimee’s foyer was a chessboard of black and white tiles. Life size, stuffed dolls, both gangly as cartoon buffoons, stood by the buzzer, dressed as a butler and a maid and each with a tray of candies in hand. Ms. Aimee never answered. The buzzer would pierce with the pitch of a fire bell, and still, she never answered. That was how loud her TV was. I would stand there, a madman of sorts, gnashing my teeth and pulling at my hair as the dummies would gaze at me, their button eyes and scarecrow grins turning ghoulish by the second.

The tipping point came when I would awake in the darkness of my room, in what would otherwise be the stillness of night if not for the music rising from the floor – an undercurrent threatening to surge into a tsunami: “I’m singin’ in the rain, just singin’ in the rain. What a glorious feeling, and I’m happy again… The rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain… I am starry eyed and vaguely discontented like a nightingale without a song to sing. O why should I have spring fever when it isn’t even spring?” As if violins ascending to a crescendo and muffled voices weren’t bad enough, I could now discern the lyrics and identify the songs. They might as well have been blasting from my own TV. I envisioned the actors – Gene Kelly, Audrey Hepburn, Jeanne Crain – performing the numbers. That I was so familiar with old Hollywood astounded me. Worse yet, that I was entertained threw me into a fluster more so than did the loudness of her TV. What was this fixation Ms. Aimee had on rain and spring? On a season that conjures flowers in bloom and doves necking? Could I, in my knowledge of her nocturnal TV viewings, subconsciously be sharing her fixation?

“At least we know what musicals she likes,” the building manager joshed.

I admitted that I liked them, too, but not at three in the morning. This had to end.

Image courtesy of psychological science.org

A judicious man in tie and blazer, the manager sat Ms. Aimee and me down in his office to discuss the situation. He was so intent for us tenants to co-exist in tranquility that Ms. Aimee consented for the volume to her TV not to exceed the number he would later indicate in red marker on post-its taped onto the remote controls to her TV sets. You got that right – TV sets, plural. Ms. Aimee had a TV in the kitchen, a TV in the master bedroom, a TV in the guest bedroom, and a TV in the living room. She kept her word… briefly… which led to more phone calls from me to the doorman. And then, one afternoon, my own phone rang.

“Hello. I just want to tell you that I am sorry I have kept you from sleeping at night,” Ms. Aimee said with a lullaby softness. “I really don’t intend to be bothersome. I really don’t. Perhaps you could try stuffing your ears with cotton the way mummies do to their babies. Babies often sleep peacefully when they have cotton in their ears.”

“Well…” No way! I should not have to alter my sleeping habit on her account. Neither was I a baby. “I’m afraid that won’t work. I would feel as uncomfortable as having a stuffed nose.”

“Stuffed nose?”

“I’m sorry. We made an agreement… You made an agreement.”

“Oh.”

A background ring sounded in the phone receiver.

“Excuse me for a moment,” said Ms. Aimee. “I’m baking apple pie.”

“Goodbye,” I said.

“Oh… Please, we must talk. We haven’t resolved anything and we must, for my sake as well as yours. For us both. And the apple pie… well… Would you care to have some?”

Just as unexpected as her phone call was, I was suddenly her guest.

What a trip her unit was. It evoked an ambience more befitting a garden cottage than an urban condo. A rocking chair along with a pair of floral-motif sofas, one lining a side window and another a wall opposite from the balcony, furnished her living room. The wallpaper bore water color images of onions and celeries and all sorts of vegetables. And a coffee table displayed framed pictures of her children (two sons and two daughters), their own children, and the children of their children. Her wedding picture stood as the central image. If her hair had been blue, I couldn’t tell… the photo was in black and white… but it had been styled in the same fashion as it was on the afternoon of my visit and as it would be for the rest of her life – a frou-frou do Easter bonnet high. Of course, a TV was the most prominent item. The only sign of modernity, it was a flat screen that hung above the fire mantel situated across the living room from the side window and was, to that date, among the largest of the Samsung models. I estimated an outrageous length of 65 inches.

We sat at a table in front of the balcony. Since the sliding glass doors were open, we could hear the laughter of children in the Huntington Park playground. I suppose a conversation between just the two of us was a long time coming; the noise problem had been ongoing for a year.

“Thank you for inviting, Mrs…” I did not always address her as Ms. Aimee. Aimee was her first name, which she insisted at that moment I call her by (she even spelled it for me) and which is another reason she was an anomaly; the Nob Hill ladies were all Mrs. So and So. However, considering her status as an elderly, I did not think such level of casualness to be appropriate. “… Ms. Aimee,” I said.

Image courtesy of www.encrypted.tbn0.gstatic.com

“That has a lovely ring to it. Ms. Aimee to you, I am then,” she said.

“Like the French actress but without the French pronunciation.”

She appeared flabbergasted, even amazed. “Yes, Anouk Aimee, though I was born way before she ever was. And you were born way after she was. How curious you should know of her.”

“Odd, actually… or so I’ve been told.”

The apple pie was the perfect degree of warm, akin to the sensation of ice cream melting in my mouth, and it had a teasing and delightful dose of sour amid the sweetness, a flavor distinct to green apples. It was exactly as my mother bakes her apple pies.

“I am sorry,” said Ms. Aimee.

“What for?” I asked. “This is delicious.”

She laughed. I had never heard her laugh before. Her laughter was mellow, almost controlled but so sincere that it had a girlish timbre to it. “I mean for the TV in the evenings.”

“That’s all right, Ms. Aimee. I mean, that’s not all right. I mean… What I mean is that I know you don’t mean to disturb me. No need to apologize.”

“What can we do?”

“At what level do you play the volume?”

Ms. Aimee procured the TV remote from a glass bowl on the mantel and handed it to me. The number 30 in red marker on a yellow post-it was taped to the back. I hardly ever went past 27 with my TV, and on the occasions that I did go to 30, it was loud, though not egregiously so. “Do you tend to go past this number?”

She didn’t answer.

I didn’t know what to say and then, “At what level did you have the volume when you would watch TV with your husband?”

“We rarely watched TV. Almost never.”

“I understand you have four TV sets.”

“That all came after he died.”

“On the occasions that you and he would watch TV?”

Image courtesy of midget momma.com

“About the level you see written on the remote. Less even. Also, my hearing was much sharper back then.”

“If you could keep the volume at the number written on the post-it, that would work well for us both.”

“I do try very much,” said Ms. Aimee with a long face, one a child would have when reprimanded. I felt guilty.

“I appreciate it,” I said.

“Voices, you see, even from the TV, they keep me company. Of course, I don’t expect you to understand. You are young. You must have so many friends.”

“I understand perfectly well, Ms. Aimee. Yes, I do have friends but not as much as before.”

Ms. Aimee seemed perplexed. “With Facebook, you must have hundreds.” Then her face lit up. In her eyes I sensed a sarcastic twinkle. I knew she was kidding.

“Very funny,” I said. From old movies to social media…what a curious intersection we were both at. “Okay. 368 Facebook friends, to be exact, about half a dozen of which I used to be close to.”

“Used to be?”

“Yes,” I said.

Ms. Aimee looked at me as a school teacher does when prodding a pupil to complete a sentence.

“They have since moved to other places and have started their own families. That is why I have few actual friends.” I chuckled at the irony of it all. A gush of wind through the balcony doors cooled my face. “To think that we were once a part of each other’s everyday existence. As every posting of a picture shows, they’ve thrived without me. ”

“I know,” said Ms. Aimee as she returned the remote on the mantel. “I’m on Facebook, too, and I know.”

This time I must have appeared perplexed.

“I may be ancient but not out of the loop with today’s goings on. My children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren, I see them on Facebook often, so often. It’s bitter-sweet. They visit me whenever they can, and when their visit is up… For all I know, yesterday’s goodbye could have been the final. If it were, then they’ve got their lives, and as you say, they shall thrive when I am gone.”

I wanted to say that, with her age, being gone was an impending reality. Dying was not the same as being on the cusp of middle age and already virtually non-existent to those once held dear.

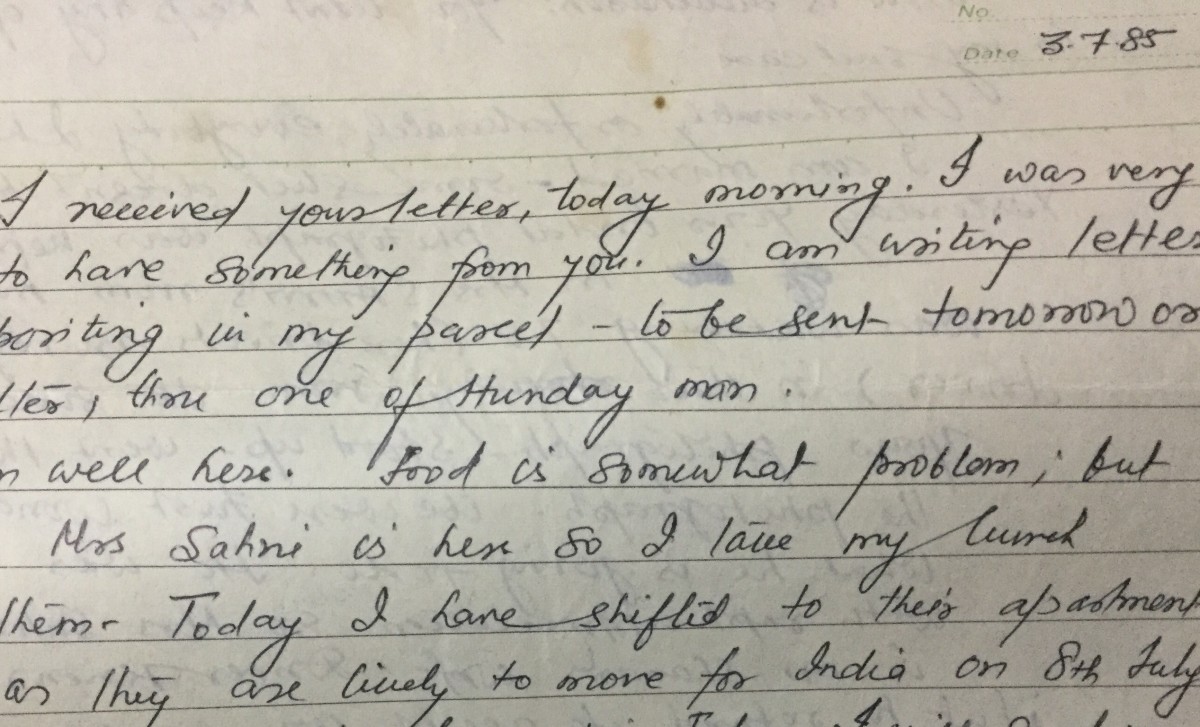

“Letters,” she said. “Far and distant as a loved one was, letters kept you both in each other’s lives.”

“I wrote letters as a child,” I said, “and through high school, even college.”

“How nice. How nice to talk to one so young and who actually knows what I’m talking about.”

“I’m older than you think.”

“So you remember the beauty of letters. Let me tell you, nothing says ‘I care about you’ the way a letter written exclusively for you does, a letter written from the heart. You can see the love in the hurried script, the pressure of the pen on the paper. Kids today, they will never know that feeling.”

Image courtesy of amazon.com

“I remember.”

“Indeed. Even something as mundane as what a friend had for lunch was a pleasure to read.”

“Lots of those on Facebook. Food pics here and there, everywhere.”

“No, no. It’s not the same. There’s a difference between clicking a button on your mobile and uploading a pic” – she simulated clicking a button on a mobile – “and describing in words the taste and smell and feel of what you ate.” She simulated writing… and in cursive, too, not in print… with eyes shut as though relishing in her thoughts her own apple pie.

I was astonished at Ms. Aimee’s adeptness with technology. Then again, how else could she have been educated a load full on the latest flat screen TV model?

“I had nice penmanship,” I said. “Gorgeous, actually. Old English type of penmanship. Thanks to the computer, it’s been shot to pieces.”

Ms. Aimee was quiet and focused on the apple pie on her plate yet saw something else entirely, something that seemed to drift into her field of vision as a wisp of smoke at once adapting solid form. “My husband and I, before we got married, we wrote letters all the time. Since we were in love, the anxiousness over the wait for a letter and the exhilaration upon its receipt was ten times… no… a hundred times… a thousand times… a thousand times greater. The sensation ate me up. I became a walking vision of joy, a human light bulb. I was a young fiancée when he fought in the Korean War. Then we married, and later his letters carried even more importance. In the Vietnam War, he was a doctor, while I was here in the homeland, a nurse. His letters were an affirmation of life.”

“How did he die?” I asked. I had been curious for a while, for even Lincoln the doorman was mysterious on this subject. Now here Ms. Aimee and I were. And again, she was quiet. “I don’t mean to pry.”

“While doing a butt buster.”

“Pardon me?”

“Have you ever done a butt buster?”

My imagination stretched far to scandalous territories: doctors and nurses, what games they must play. “I’m not sure,” I said.

“You either know or you don’t. A butt buster is not anything you forget.” Ms. Aimee took my empty plate and disappeared into the kitchen down the hall. She didn’t walk as much as she waddled.

“I guess… Yes,” I said. “Do you need any help?”

Not seeming to have heard my question, she said, “Well, that was how I became a widow.” Her voice, faint and faraway, possessed a dreamy quality, such as voices we hear in our memories.

“I’m sorry.”

“It’s a bicycle ride uphill.”

“Is that all. I got the impression it was something else. No then. I’ve never done a butt buster.”

The Grace Cathedral bell chimed. Late as it was in the day, children’s laughter from Huntington Park continued to waft into the balcony, and since this was summer, the sun remained vibrant. I stared at the sky. What an incandescent blue it was, as if brilliant days such as this were the permanent order of the universe, as if Sundays were exempt from storms and dark clouds. Then it dawned on me: what was I doing chattering with an old woman on a Sunday afternoon? Keeping company with Ms. Aimee was quite refreshing. Had this been an ordinary Sunday, I would have been strolling around the city, marveling how couples around me had progressed from strangers to intimates since that is what I do every day in forming a connection to the world. I observe people – couples holding hands, in a café sipping from the same straw, laughing in harmony; parents; newlyweds; pairs of all ages. I am drawn to lovers. A mere night before Ms. Aimee called, I had seen a blond boy in his early twenties at the subway station, in owl glasses and black sneakers and with a condition that caused his leg to shake while he stood stationary. Watching him, I wondered about the bullying that had tormented him as a child on account of his leg, commiserated with his isolation, his pain. Then I envied him as I was envying him on that Sunday. He had been smiling because he had a friend, another young man, one who was large and hefty and who held him in a manner that made it evident they were in love.

Image courtesy of www.rolandindonesia.com

“Oh, that’s okay about my husband’s passing,” Ms. Aimee said, again in my midst. Ignoring my gesture that I was full (which I really wasn’t), she placed another slice of apple pie before me and poured me more milk from a porcelain pitcher. “My husband got a heart attack halfway through a butt buster. He died doing what he loved. That ought to be a consolation. As for you, you haven’t experienced real struggle and victory unless you’ve done a butt buster.”

“Have you?”

“When I was young. A long, long time ago. He and I would go up a hill, then go back down, then go back up again just so that we could put to shame cyclists around us out of breath. We were arrogant. Show offs. That’s how it is when you’re young, as you certainly are aware of.” Ms. Aimee smiled a good-natured smile.

“I’m not that young,” I said.

“But you know what I mean. There must have been something you were good at that you wanted to show off to the world, something you’re good at still, that your mother must be proud of.”

I shrugged my shoulders. I could never get a partner, no matter how many my bed mates or how seductive my iron-pumped pecs. I was fundraising at a non-profit organization, doing my share in making the world a better place, and still, I felt empty. For all the esotericism of non-profit being a noble vocation, it was, for me, a job I was stuck at and one in which I wasn’t applying my true passion – a creative ardor for words and images that in my youth had been insatiable but that a routine existence had since squelched. I couldn’t even recall the last novel I had read. And as for close friends, whatever happened between us? Nothing. Absolutely nothing. A falling out would have been a cause on which to peg the severance of ties. Instead, we drifted apart for the simple reason that nothing ever stays the same.

“Really, come off it with this old nonsense,” said Ms. Aimee.

“I’m almost 40,” I said.

“40 is a kid. You’ve even got a few years to go before you get there.”

“One year.”

“You’re a baby. For the record, I’m 84. My, what I’d give to be 50 again.”

“50?” I couldn’t imagine myself at 50, yet here Ms. Aimee was, talking about 50 as if it were 20.

“Or about your age, when my husband and I first moved into this building. How lucky we were to have spent nearly our entire lives together in this neighborhood. Where we are, it’s unique among all the places in the world.”

“True.”

A somberness suddenly overcame Ms. Aimee. She appeared to be a different person, as though something latent in her had been snapped awake, a volcano dormant for centuries and now about to erupt. “Who am I kidding?” She stared at me in the eyes. I could have sworn her own eyes flared with the red of lava. “That my husband died doing a butt buster is no consolation. It was stupid of him. I begged him not to. Did he listen? No. Never. He was the kind of man who did whatever he wanted regardless my pleas. For a doctor, he should have known better than to defy the limits of his ailing body. Look what his stubbornness has gotten me – a collection of televisions. Sometimes I think he loved himself more than he did me.”

“I wouldn’t say that,” I said.

A stony stillness and then, “How would you know?”

I bowed my head. Ms. Aimee was right. How dare I.

“Are you an expert on love?” she asked.

Image courtesy of usercontent2.hubastatic.com

“No, not by a long shot. I’m the last person to comment on the subject. I can’t even tell someone to stay.” Why I blurted this out beats the hell out of me.

“Not easy to hold onto people, you’ll discover, if you keep conversation on the surface. Even on Facebook, someone can unfriend us at any moment. No depth there.”

“Relationships are as fragile as glass.”

“Or as sturdy as steel,” said Ms. Aimee.

Right there, her analogy of human connection to the most durable of man’s material inventions… such a conviction could only have stemmed from a history of having given plenty of herself to one adored and in having received back in as much abundance. In images on the coffee table of her together with her husband, their smiles were uncompromising. Theirs had been a happiness that could not have been feigned. Sometimes I think he loved himself more than he did me, Ms. Aimee had said. Sometimes… not often, not always… and on these rare occasions, she admitted that the sentiment had existed in her head. The truth was in front of me: a widow who sought solace in social media and in current home viewing trends for the loss of a husband who had devoted himself to her ever since the word “television” had been introduced into the lexicon of our everyday vernacular.

“You were married for over half a century,” I said. “That is no small feat. If I’m a fraction as lucky as you’ve been, I might experience for myself a love the strength of steel.”

“Look at where you are,” Ms. Aimee said. “You already are lucky. This is a charmed neighborhood. Magic can happen if you allow it to.”

“The movie trailers that occupy the parking spaces around Huntington Park for days on end can be an annoyance.”

“I don’t mind.”

“Not once have I spotted a movie star.”

“You don’t need to. You make your own movie out of your own life with yourself as a star. That you can do it in this lovely neighborhood is a marvel. Such beauty. After all these decades, I remain in awe of Nob Hill. We do what we can to protect it from drastic change, and change I have seen a lot of, mind you. It was in this living room that my husband and I witnessed Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon, in hazy black and white. Flower Power, the AIDS epidemic, the dot com boom… many events that have started here in this city and that spread across the globe… we’ve lived through it all, in this building, yet the neighborhood has been unscathed. The Fairmont Hotel is as it has always been. The Brocklebank is the way Alfred Hitchcock filmed it. Neither Huntington Park nor the playground is going anywhere because this place will always have families. They will be living out their own stories, their own movies, and leaving their mark. You’re doing the same. There’s a piece of you on every bit of sidewalk right in front of this building and in the air you breathe as you step onto your balcony. Do realize, though, that there are also changes that are necessary, changes that bring out the best in us, that teach us to be patient, to cook for and tend to someone, to… to forgive.” Ms. Aimee gave a bemused grin. “Of all the foolishness, a butt buster at his age. The day it happened, I had milk and apple pie waiting for him exactly where you are. I was expecting him to rush through the door and devour every bite and chug down every drop without a word like a child. That was the way he was – self-absorbed as a child is and oh so tender, too. He was always excited to finish off a butt buster with an apple pie. And I… well… it was bliss to watch him eat it.”

Image courtesy of wordpress.com

” I remember him,” I said.

“Do me a favor, a gutsy favor.”

“Okay.”

“Say ‘stay.'”

I was mute.

“Go on,” Ms. Aimee said.

“Stay,” I whispered.

“Louder.”

“Stay.”

“That wasn’t too hard, now was it?”

WTF! I just wanted to discuss the TV noise. For a non-descript lady whom I had perceived as a nuisance of a neighbor in possession of the most dismal of wardrobes, Ms. Aimee sure got me choking up. She got me to thinking of my own mother. My mother had been so agile in her walk that whenever she would come for her six-week visits, I would count down the days to her departure so that I could flee out the door, into the dens of iniquity in the south of Market Street and in the Castro district, there where I would drink, dance, and fuck, lose myself in a demimonde of clubs and drugs until midnight became dawn and the sunrise signaled sleep so that I could be at it yet again with rejuvenated vigor upon nightfall. I missed her. I wish she were regular with her visits as she had been in the beginning. I wish she could be a young mother always. I wish I could have a second chance at youth. I wish I hadn’t chosen jobs primarily because they allowed ample time for my party schedule. I wish I had looked into the eyes of those I had kissed and told them I loved them. I wish. I wish. I wish.

“You know, I’ve only walked onto my balcony five times in all the years I’ve been here,” I said, “twice to wash the sliding doors. I’ve got vertigo.”

“I do, too. Still… Ah! Children’s laughter. You hear that? That’s something. When there’s no laughter, then a voice fills the silence. A passing voice, a small, distant voice, whatever voice it is, it’s still a human sound. And when there’s no voice, then it’s the voice of nature, be it a strong wind or a subtle breeze.”

“I keep the balcony doors shut.”

“Oh, no.” Ms. Aimee wagged her index finger in severe disapproval. “No, no, no. You must have your balcony doors open. Listen to what’s out there. You will no longer feel as though you were trapped in a box, separate from everyone and everything. You’ll feel that you belong to the world, as you must.”

How did she know of my yearnings? “You’re right, Ms. Aimee,” I said.

“There’s a new voice to my family,” she said. “He’s six months old.”

“Congratulations.”

“He’ll be visiting me in the next month. If you please, I don’t want phone calls in the middle of the night to interrupt baby from sleep or the buzzer causing a raucous.”

So she had been ignoring the buzzer.

Image courtesy of i.pinimg.com

“Babies, you understand, need heaps of sleep.”

Stuff its ears with cotton, I thought. “I understand,” I said. “Do know, Ms. Aimee, that no phone calls in the middle of the night or buzzers buzzing will occur should you keep the TV volume low. Baby’s peaceful sleep depends wholly on you.”

“Oh,” she sighed.

I could not leave her on such a discordant note. “The TV doesn’t provide anything special to you or any of us, Ms. Aimee. Everything it broadcasts is watched by anybody, anywhere. It’s a distraction to what genuinely matters. These walls, these family pictures… the stories they tell are what’s worth listening to because they’re unique to you, gifted to you to cherish. So cherish them. Honor them.”

Ms. Aimee scanned her surroundings, as if seeing things and people visible to her alone. “The sound of our memories can be the most strident as well as the most melodious,” she said and then, with the mildness of a prayer, “How he so loved my apple pie.”

From here on, the nights were silent. Although the refrain to a Hollywood musical no longer invaded my room, I would lie awake and imagine Ms. Aimee downstairs dancing cheek to cheek with her husband’s spirit, her footing firm and movement graceful, herself giddy with remembrances to sustain her from sunrise to sunrise. I fancied Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers as the movie stars resurrected on her TV. In all the dazzle of the silver screen – he in top hat and tail, she in a gown of oscillating feathers and billowing skirt – they were dancing on a stairway to paradise, heaven’s gate a few turns and spins away from Ms. Aimee’s balcony.

Ms. Aimee died last month. So desirable is this piece of real estate that her unit had scarcely been on the market when a buyer snatched it. I haven’t met the new tenant (or tenants) nor do I care to. That I have experienced no disturbance is fine with me, which leads me to believe that whoever Ms. Aimee’s replacement is must be young, maybe not as young as I had been when myself a new tenant, but in the phase of life where a daily itinerary consists of leaving home early in the morning and returning late in the evening because the world out there is for the taking.

As for my own home, it has remained unchanged in the near 20 years since I moved in -landscape canvasses that hang on white walls, white floor carpeting, and white upholstery to match white draperies – and yet, changed it has. Faint smudges of soot on the carpet infuse the unit with an atmosphere of having been lived in. The paint chip on the base of the bathroom wall, noticeable only when sitting on the john, has lengthened from a speck to a streak like the trail of an invisible snail, slow to form but as dogged as time itself to arrive at a fixed destination. The socket frames are lopsided. The golden door knobs are tarnished.

On account of my mother’s challenged knees, my parents considered selling since they doubted they would visit with the frequency they once had. I initially acquiesced, only Ms. Aimee’s words refused to let me be: where we are, it’s unique among all the places in the world.

Do not end. Start afresh. Refurbish. Revive. Stay.

Lo and behold, the prospect of a new beginning has fortified a will in my mother both mental and physical, she whose passion is creating a gentle and gorgeous haven for her family. I myself hear it every morning, this heralding of a rebirth. The laughter and voices that enter through my open balcony doors from Huntington Park grow ever greater in their zest for life upon each passing day. They beckon me forth towards the wealth of humanity, out there where the touch of another need not be a transient pleasure that dims my soul, but a spark that transforms my body into a vessel of eternal light.

Image courtesy of amazon.clikpic.com