Image courtesy of nathanhiemstra.com

Every neighborhood has a haunted house. When I was a kid, the spooky spot in my neighborhood of Dasmariñas Village – an enclave in Manila of gated abodes and wide streets – was a miniature villa with plaster pillars, arches, and grime-layered windows. The only abandoned address in the compound, with signs of fire having gutted its interior, it was a sight to provoke the imagination. No other dwelling existed within 500 paces of its radius. I don’t know why the rumor that the house was haunted. I never heard any accounts of spirits having been spotted. Neither was I told tales of sinister dealings or violent deaths that had led to its condition. Its bleakness, like Dracula’s castle, was enough for the driver to whisper as our car happened to pass by in the evenings that ghosts inhabited its rooms. I was six years old, and the concept of a ghost was new to me. Whatever I imagined, the dread with which the driver spoke of them implied that to stumble upon one would be a terror a like no other.

This was the birth of my fascination with elements of the dark. In the 1970s, a TV program on paranormal activities called the “The Sixth Sense” was obligatory viewing along with “Kolchak: The Night Stalker,” a detective series that involves scenarios a hybrid between the supernatural and sci-fi, and “In Search of,” a weekly documentary on such phenomena as the Loch Ness monster, aliens, and the Bermuda Triangle. “The Amityville Horror” (1979) gave me roller coaster thrills, even though I neither read the book the movie is based upon nor saw the movie itself, and to this day, when I gaze in the mirror in my foyer as I turn off the lights, a shiver runs through me at the mere thought of the urban legend that should I chant “bloody Mary, bloody Mary, bloody Mary,” a hag with bloodshot eyes would stare back at me.

Image courtesy of wordpress.com

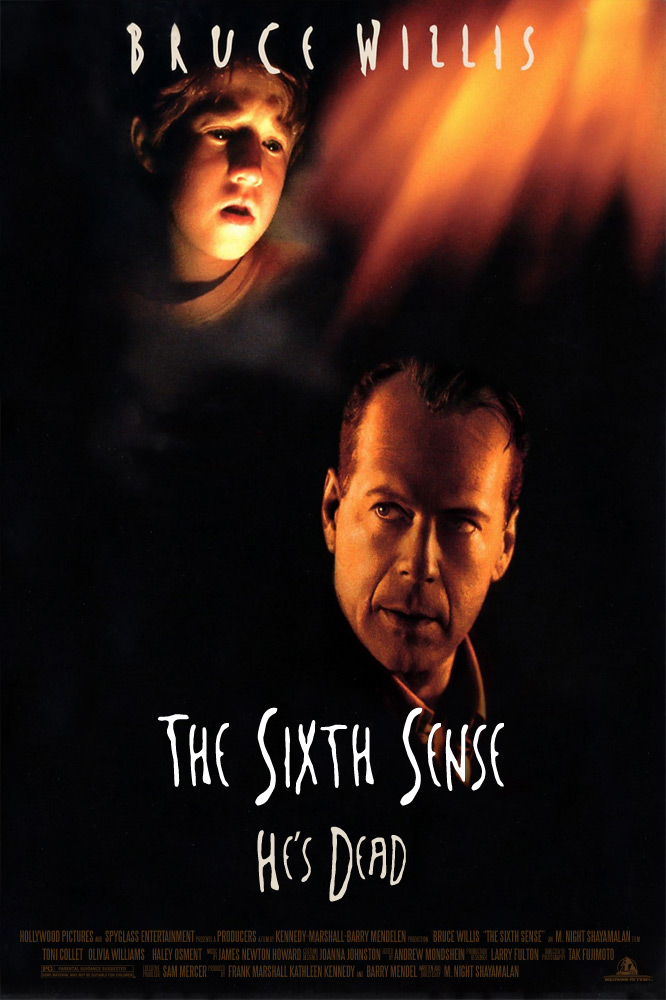

Although I have never seen a specter, I have friends who have. Chris claims that on the night his grandmother passed away in the Philippines, she rang his doorbell in San Francisco and was standing on his doorstep. Pablo encountered an old man sitting at his kitchen table, whom he described as a transparent figure made of prisms of light. Mark woke one morning to find a priest kneeling in prayer at the foot of his bed, only for the priest to disappear after Mark shut and opened his eyes once more. “Were you scared?” I asked. “No,” he said. “I felt… at peace.” Then there’s Doug, who sees dead people, exactly as Cole Sear (Haley Joel Osment) in the film “The Sixth Sense” (1999) does. Doug confirmed Pablo’s impression of a phantom as diaphanous, Mark’s experience that a visitation need to not be frightful, and Cole’s avowal that in a haunting, the temperature grows cold.

If ghosts are supposed to be friendly, then why our fear of them and what do they want from us? In “The Sixth Sense,” they are not particularly spine-chilling. It’s the kid, Cole, who’s the creepy one. He’s cute but unnerving with his dour expression as if he were an old man who has seen too much of a bad thing. They are everywhere around Cole, the deceased, inescapable and terrifying, a presence that devitalizes like a cancer. Among the things he sees are bodies in Colonial period garb hanging from their necks in the school hallway and a cyclist, just killed in an accident, peering at him through his car window. His ability to discern and communicate with habitats of the netherworld renders him socially gauche. His mother, Lynn (Toni Collette), doesn’t know what the deal is with her ten-year-old and here enters child psychologist, Dr. Malcolm Crowe (Bruce Willis). Like any parent, she wants her boy to be normal.

Image courtesy of proxy.duckduckgo.com

Normal. So Cole wants to be like the rest of us. It certainly is a bizarre ability to see folks who are no longer with us, but there’s something about Cole that we can sympathize with. We all have our quirks and talents. Some of us have a talent so disproportionate in amount from others that as children, we’re called prodigies. While it is remarkable to be in the presence of a Picasso, who by the age of 15 was creating paintings that exhibited sophisticated depth of perspective, being special can be anathema. Parents and the public harbor ambitions for a prodigy at the expense of weekend sleepovers and afterschool excursions to the mall. With neither a childhood nor the option to choose one’s own future and with expectations exorbitant, the wunderkind could be at risk of being a lost soul, the luster tarnished. Andrew Halliburton is a mathematics genius who, today at 22, wipes tables at McDonald’s. Megan Ward at ten designed and manufactured a key chain that contains a device to assist people to quit smoking, but at the age of 15 struggles with reading and writing. At six, Michael Kearney graduated from high school; at eight, finished junior college with an Associate of Science in Geology; and at ten, earned a B.S. in Anthropology. At 31, he hasn’t decided yet what to do with his life and has proclaimed that he simply wants to be “normal.”

A large factor to success is failure. With failure, we learn from our errors and therefore exert ourselves to excel at the next round. Often, prodigies are ignorant of the rewards of perseverance because they are praised for their skills rather than for their efforts, and their skills are as second nature to them as eating ice cream. Absent is the motivation to push oneself to the next level. When the motivation is there, however, that is when the world is enriched with the likes of Picasso, Mozart, and that gymnastics rarity, Nadia Comaneci. Although Cole Sear in “The Sixth Sense” isn’t a genius, he is gifted with a precociousness on account of an uncanny skill that separates him from his peers. The only people who want to befriend him are dead. How to explain this to mom, Dr. Crowe, and classmates? It’s freaky.

Image courtesy of pastemagazine.com

For Cole’s benefit, lonely lad that Cole is, Dr. Crowe believes him. He is also counseling Cole for a reason. Here we learn why sometimes the departed cannot be silenced and why our reaction to them: they have unfinished business on earth, be it a final bid of farewell or a declaration of love – acts we take for granted but realize are precious only when we are confronted with death. As such, their restlessness in purgatory gives us goose bumps. The psychologist thus advises the boy to use his talent to his advantage. Rather than allowing his sixth sense to restrain him, Cole should allow it to liberate him.

To reconcile the living with the dead is no small responsibility. That this comforts both parties is more a blessing than a curse. We all have a knack for something, and perhaps this is why ghosts intrigue me. When I die, I do hope my soul travels on to heaven, my tenure on earth complete. Should I wish to speak from beyond the grave, then I shall do so through some of the best parts of myself I leave behind – through the love that colors the air within the walls of places that have provided me the richness of food and family, a coconut pie, and the shear force of written expression.

Image courtesy of wordpress.com