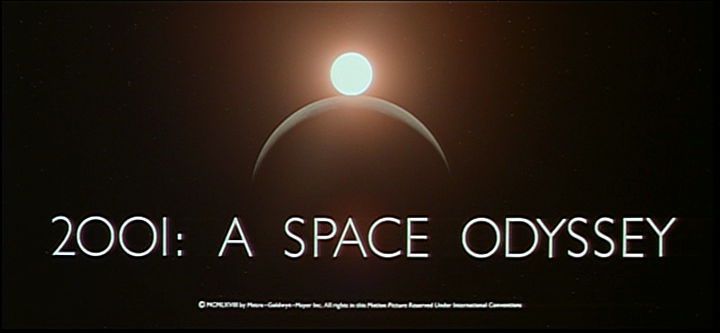

Image courtesy of doctormacro.com

I discovered “A Place in the Sun” (1951) in a moment of boredom. I was in high school and accompanied my mother to a dinner hosted by a family friend, Mrs. Y. Why I tagged along beats me. I was the only male present and the only teen. Maybe I was there on account of Mrs. Y’s sweet and sour pork, the best I’ve ever had – meaty and crispy as a pig roasted over an open fire; none of the battered lard served at San Francisco Chinatown. To keep myself preoccupied, Mrs. Y allowed me to stay in her bedroom, where I could watch a betamax cassette. She was a patroness of Repertory Philippines, a theater group that mounted Broadway productions with a Filipino cast and where Lea Salonga had her start in “Annie.” Mrs. Y’s enthusiasm for stage extended to films, as well. She had a collection of studio-era classics, and movie star biographies lined shelves. There he stood out like a light tower in a starless night: Montgomery Clift on a bookbinding.

Image courtesy of squarespace.com

One hand in pocket and the other carrying a trench coat, blasé in suit and loose tie with hair windswept, Montgomery Clift cut the image of a loner on a journey in which he had lost his direction. I had never heard of the actor before. I read the back jacket, and I skipped a breath. It stated he had been homosexual. Rock Hudson’s death from AIDS wouldn’t happen for another year, so it surprised me that a leading man, and one extraordinarily handsome on top of that, had been gay. Forget betamax. Forget sweet and sour pork. I was hungry to know the secrets and same sex escapades of a film legend. Every photograph of Clift from his early youth to those shot to coincide with his ascension in Hollywood roused my desire. Then there were the photos with Elizabeth Taylor. She was 17. He was 30. The pairing of two individuals whose looks were made for the camera was ingenious movie marketing because over three decades later, I was sold.

What a tragic tale “A Place in the Sun” is. That’s what hypnotizes me about it. We cannot keep our eyes off beautiful lovers who emote desperation, who lose themselves in each other as if every kiss were the last. Such a sight is akin to a marriage between the sun and the moon – dynamite. Clift is George Eastman, a poor relation to a wealthy uncle (Herbert Heyes) who offers him employment in the assembly line of a shirt factory. There he meets Alice Tripp (Shelley Winters). She’s homely but doting, and in her George finds comfort. They have an affair that leads to her getting pregnant.

One problem: George has the fire of ambition that cannot be squelched. As Uncle Eastman promotes George to a managerial position, he invites the latter to a fancy party, where the upstart meets society girl Angela Vickers (Elizabeth Taylor). Given Angela’s affluence and stunning appearance, she would be the ticket to the highest echelon of society. George would at last have his place in the sun. What to do about Alice?

Image courtesy of cloudfront.net

I am not a superstitious person, but I do believe in signs. It might not have been by chance that my interest in “A Place in the Sun” started at Mrs. Y’s. Mrs. Y was an eccentric in flowing gowns, heavy eye shadow, and glossy lipstick. A portrait of her in her earlier years that hung in the living room presented her seated with the regality of an empress. Her salt and pepper hair had been the curled coiffure that it would be in her later age, and the style with which she made up her face had not changed. Due to her social standing, she had among her friends tycoons and politicians. You’d think Mrs. Y was the Angela Vickers type. Not entirely. Her husband had left her for her best friend. If Mrs. Y was garrulous, it was because she was lonely. According to my mother, she spoke a lot about her ex, and always with a hint of hope. She still loved the man, and she would do so for the rest of her life. Although nobody commits a mortal sin, hers is a sad love story. Now here I am to tell it.

Mrs. Y discovered her husband’s infidelity when, on a cruise in which her best friend and her own spouse accompanied the couple, the best friend had in her arm a stuffed bear that Mrs. Y had pointed to her husband upon passing a store window. She had wanted him to buy the bear for her, but he had brushed off her wish as childish. That’s like a guy giving his mistress a piece of jewelry the wife expects for herself. Mrs. Y didn’t say a word. She wasn’t going to cause a commotion on deck. So husband and wife separated. They couldn’t divorce since, being a Catholic country, the Philippines forbids it. The church did grant Mrs. Y an annulment, a hypocritical procedure, considering that Mr. Y had sired seven of Mrs. Y’s children. Such is the law there. It gave the best friend the right to leave her husband in order to be with Mr. Y.

I don’t know how long ago Mrs. Y’s marriage had dissolved before my family got to know her. I only have memories of her as a solitary woman in her sixties and seventies, dolled up in the fashion of a dowager in a Chinese opera. During one of her home luncheons, this time with my mother, sister and me as sole guests, she was glowing over a present Mr. Y had given her. It was a betamax machine. On it was a note that said, “love from…” Despite a painful break-up, the two managed to remain friends. He would give her mundane gifts – home appliances, a case of soft drinks, nothing romantic – yet Mrs. Y would read a double meaning to his generosity and the closing to each note with “love.” My mother often wanted to shake her on the shoulders and say, “He’s not coming back.”

My mother was right. Mr. and Mrs. Y’s children came to accept the mistress. The woman proved her worth as she nursed Mr. Y back to health upon his falling gravely ill. He would eventually pass on, but not before his mistress after whom he would name a theater, his personal Taj Mahal.

Image courtesy of gstatic.com

It’s strange how our pursuit to bask in the sun’s warmth can lead to coldness. Montgomery Clift was gifted and charismatic, headed for greatness, but tortured over his homosexuality. He lost his looks in a car crash, then died at the age of 45 in a haze of booze and pain killers. Elizabeth Taylor, for all her beauty and talent and husbands, grew old alone. Certainly, we are masters of our destiny. Yet no matter how firm our belief in the path we have chosen, a wrong or missed turn can lead to a cruel blow, sometimes one more severe than we deserve. What had Mrs. Y done for life to repay her with a love that would never be returned? All who knew her remark that she never said a bad word of anybody, not even of the best friend who had betrayed her. Mrs. Y died of cancer some years ago. A picture of Mr. Y stood by her deathbed. His face was the last human image she saw.

When George Eastman has his final walk on earth on his way to the execution chamber, his thoughts are of Angela. A blown up image of the lovers locked in a kiss covers the screen. Angela was everything in life to George worth killing and dying for; eternal faith in her would be his salvation. We can guess at what imaginings of a reunion with her one and only love must have consoled Mrs. Y in her final hours.

Image courtesy of thefilmspectrum.com

Maybe this is why some of us need to believe in God and an after life: when all things on earth fail, we can make them right in heaven.