Image courtesy of danielgawthrop.com

Publicizing my first novel, “Potato Queen,” introduced me to places and people whose paths I would otherwise never have crossed. B.D. Wong was among the 100 listeners for a forum that the Asian American Writers Workshop in New York sponsored featuring me and a Canadian writer named Daniel Gawthrop, who had penned a memoir about his love of Asian men entitled “The Rice Queen Diaries.” At the Saints and Sinners Literary Festival in New Orleans, I was a member of a community of writers and publishers united for a weekend to give credence to the LGBT voice. And at Books on the Square in Providence, the store manager – a grandmotherly woman in gray bun and a knit shawl – told me that I was sitting in the chair that a then-unknown Dan Brown had sat in and had held court to an audience of zero. One of the most rewarding experiences, however, would have to be my talk with the students at the Providence Academy of International Studies (PAIS).

PAIS is a high school that consists largely of immigrant kids from economically challenged families. The PAIS librarian had learned about me through my publicist and invited me to speak. Given that “Potato Queen” explores the segregationist relationship between gay Caucasians and Asians in 1990s San Francisco, I was concerned about the students’ openness to the subject. My high school in Manila never had a gay awareness curriculum of any sort, and guys would taunt me for my soft appearance. As such, my perception of adolescents was that they could be myopic and mean.

Image courtesy of media-cdn.tripadvisor.com

Not so with the students at PAIS. It turned out that the librarian, Peter, was gay and out as was the mayor of Providence. Sexuality was not even an issue of discussion, although some of the kids did ask if I was dating anyone and if I had ever been with a girl. With my answer to the latter a no, one boy cheekily questioned how I could possibly know that I don’t like girls if I hadn’t tried them.

The talk was in the library with the audience gathered around a table. There were about a dozen students, which made for a conversational atmosphere. Yet I was nervous. When I was their age, I believed adults of authority in my school to be above the travails singular to the very young. That was why we called them teacher, guidance counselor, and principal. Insecurity was meant to be the burden of adolescents alone. Now here I was, 20 years out of high school, with a book on an adult man who experiences alienation and bouts of negative self-image, the stuff of teen angst.

So that I wouldn’t be stumped on what to say, Peter had e-mailed me guide questions: Why did I become a writer? How do I prepare for writing? How do I develop a voice? How do my characters speak through me? What should the students think about doing now while in high school and later in college?

I had prepared my answers and I had practiced them. I had won the gold medal for an oratory competition in high school and the first place cup for one at the American College in Paris during my junior year abroad. And still, I was nervous. I sat at the head of the table with hands clasped together in front of me. Peter must have introduced me. A pen must have tapped. Paper must have rustled. Yet the only sound I remember to this day was the hum of silence that permeated the library, like silence before a storm, in anticipation of my rattle-ridden speech:

“I became a writer because of my need to be heard and seen. Being gay and being Asian, I was invisible or I felt I was. We all feel a sense of isolation. Certainly, each and every one of you does, particularly at this stage in your life where you’re forming your identity, discovering where you belong, what groups of friends you fit in with. You may not always feel wanted, but it’s precisely this feeling that fuels your drive, your ambition to prove yourself. If the world were a perfect place, then what would you have to fight for, what need would you have to prove yourself?

Image courtesy of lh6.ggpht.com

“I started with a journal. That’s the best advice I can give all of you, whether or not you’re interested in writing. Record your thoughts for the day, an experience with a friend, a teacher. Express on page your dreams, your hopes, your hardships. Don’t think too much about what you write. Write in your journal as you would an e-mail to a friend. Write the way you speak. Writers are known to have a so-called written voice. Writers don’t consciously think of this voice. It’s something that’s inherent in them, as second nature as breathing, eating, and sleeping.

“Whatever stories you have to tell will come out in these pages. You don’t need to look far for a story. You need only to look within yourself. The stories your parents tell you about themselves when they were young, your brother’s or sister’s story about getting into a fight with someone, your own stories about the emotions you go through over someone you like… all this is material. Every day of your life is a story waiting to be told. From the moment you wake up, each decision you make each minute leads to something. You are the author of your life.

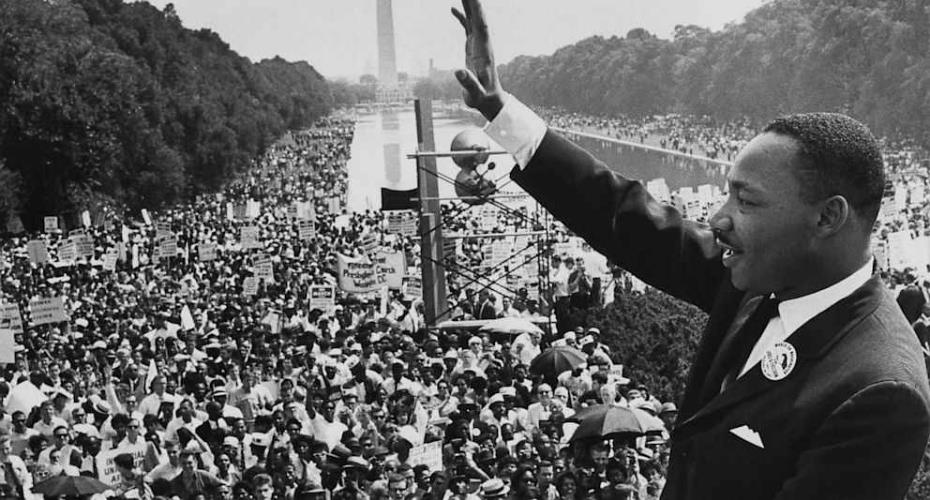

“When I write, I think of the people first that I would like to write about. I get my ideas for characters from my friends, my family, people I don’t know well but have sparked my interest for whatever reason. A little of me exists in all of the characters I create. I tend to project my frustrations and desires and dreams onto them, and from there my story is born. People make stories. Stories don’t make people. It’s the decisions that people make that lead to events. People caused the Iraq war – Bush, Hussein, Conde Rice, bin Laden. It didn’t start on its own. Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr… they propelled the Civil Rights Movement.

Image courtesy of wordpress.com

“My advice is for all of you to look at every day as a learning experience. The films you see, the songs you listen to, the TV shows you watch, the materials you read from People magazine to the newspapers to a book – have an opinion about them. Do you like something? Why? You don’t? Why not? Take the time to understand why you react emotionally to an experience. Don’t just say, ‘I’m sad…I’m happy… I’m pissed’ and then leave it at that. This is the best way to develop your analytical skills. And you will certainly come across as a more intelligent person and a person worth listening to and believing in.

“Be good students. Study hard. Put pride into your work. There are times when it will be tough. You might not do well in a test, have a major argument with your parents, a falling out with a friend. That’s part of life. Those are obstacles you need to overcome. To experience the joy of success, you need to fail. To be a winner, you need to lose. To believe your worth something, you need to be rejected. That’s the yin and yang of human existence. “

The students clapped. They smiled and they thanked me. On the drive to the train station for my ride back to Manhattan, I made a straightforward remark that generated from Peter a straightforward reaction:

“I wonder if I made a difference in their lives.”

“You did. I know you did.”

Image courtesy of yourmoneygeek.com

:origin()/pre14/4c85/th/pre/i/2014/118/1/d/fake_smile_by_marii85-d7cxieo.jpg)