Image courtesy of summitmedia-digital.com

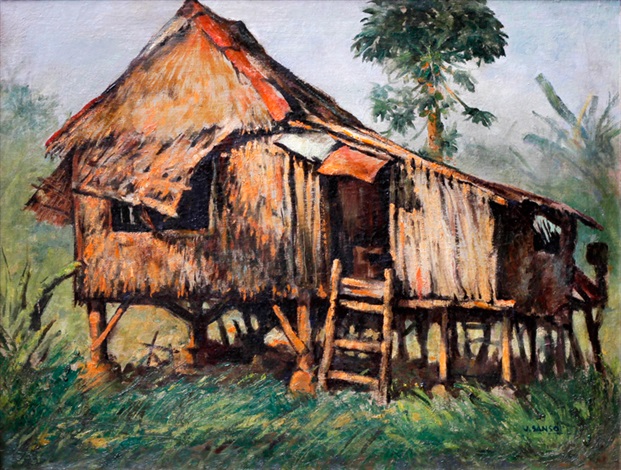

His entire life has been about the earth. He was born in a two-room shack, a wooden structure with a triangular roof made of coconut husk. Laundry hung from the front door awning, and inside, above a straw mattress, a poster of the Virgin Mary was tacked onto a wall, the once vibrant blue eyes and white gown dulled by age and dust. He didn’t know how long the poster had been there; it had been old ever since his first memory. The fifth of six children to farming parents, he recalls as his first sound the cry of a newborn sister; his first smell, the pungency of sweat; his first taste, salt; his first sight, blue eyes gazing upon his mother, her skin an intense sepia against a yellow frock as barefoot siblings clustered around her.

While he relishes most memories of home, he detests salt… it leaves an aftertaste of loss and labor… but salt is inevitable, for it flavors his every meal: meat soups and chicken soups and fish with rice, food he grew up to and which now the cook to a family for whom he works prepares daily. To subdue its taste, he routinely consumes something sour; sour bears remembrances that are good. At home, calamansi and mango trees grew on four hectares of farmland. His father would pick the mangoes while green. His mother would serve them sliced and to be eaten dipped in fish paste. Calamansi juice was a staple of every meal, its citrusy sourness tempered by a pinch of sugar. The fruits were earth’s blessings that provided his family its means of subsistence, which father and mother would sell at a roadside stall across the farm.

And then it was just father. Illness claimed mother when he was thirteen. He and his two sisters and three brothers would alternate between tilling the land and operating the stall. Although his brothers had built a larger shack due to a typhoon’s destruction of their home, he knew things would be better with one less body to feed and shelter. Like all boys with a vision, he saw the city as a mecca of opportunities, so off he ventured when he was old enough to claim independence.

His father, from whom he had inherited a build that was slight and sinewy, gave his blessings. Work hard, said his father. Father and son, now the taller of the two, stood underneath the front door awning. A shirt with a Coca-Cola logo was hanging to dry. A hot breeze caused it to flutter. Dust browned his father’s white undershirt. His father’s pant hems were rolled above the ankles, showing off feet as burnt as ember and as parched as arid hills.

Image courtesy of artnet.com

The opportunity was a garden. However, for the remainder of his youth and through early adulthood, he would tend to many gardens before finding contentment in this one. They had been large gardens with swimming pools and tennis courts and towering trees against stone fences that separated neighbor from neighbor. Mistresses of houses were ornery. Masters were drunkards. Their little children were rascals, spraying hose water through his bedroom window by the garage during an afternoon nap or mimicking their mothers with snaps of their fingers as they ordered him to trim the bushes, rake fallen petals, and clean the terrace of bird droppings. Even though this garden is not the grandest, it belongs to a nice family. And it is the loveliest of all. Grass once scraggly is today even. Life burgeons where weeds and wilting stalks once dominated. A coconut tree stands beside a guava tree and a mango tree beside a banana tree, each one situated along a periphery wall lined with an assortment of leaves. Spade-shaped leaves, leaves the length of his torso, leaves that resemble paper streamers, chicken claws, and gargantuan bird feathers… all glisten under the sun as if coated in honey. Beneath the trees are clay pots the height of a barrel with orifices the diameter of a gong. Wood-carved benches, unadorned and unvarnished, are positioned on each end of the garden. This is truly an Eden. For the first time since leaving home, he feels close to the earth; he bears the title of the gardener and the responsibilities it entails with pride.

Three French doors to an eastside veranda open into the garden. The house is a white limestone two-story abode. A husband and wife in their eighties live here, the first elderly couple the gardener has been employed by. Their age appeases the gardener; he senses in their daily rituals an easiness to living that comes with wisdom. In the five years since the gardener’s arrival, ma’am hasn’t changed any. Her hair remains black and meticulously set in a bun, and despite moving with less briskness, she is still mobile. Sir was once able to stand upright and walk with a cane. Now he is stooped over a walker, his complexion all the more ashen against thinning white hair. Nevertheless, his eyes and his voice possess authority. When gazing at a subject, he does so with the intensity of studying its inner machinations, whether it be a hardboiled egg or his wife. When summoning a maid, his voice resonates across the garden in spite of its gentleness of intonation.

Every morning, sir and ma’am breakfast in the veranda. They rarely acknowledge the gardener nor does the gardener acknowledge them; he is often a good ten yards away. Given the earthy tones of his shirt and pants and his sun blackened complexion, he disappears among his surroundings, and with eyes and lips as stolid as those to a countenance carved in a mountain wall, he eludes attention. The only occasions morning greetings are exchanged are when the gardener is close to the veranda or when either sir or ma’am have a specific chore to assign.

A grandson lives with the couple. He is in his late twenties, a few years younger than the gardener. The grandson never joins his grandparents for breakfast. He usually appears at noon, dressed in shorts, then plops in a chair at the meal table, folds his arms over his stomach, and outstretches his legs as sir continues to read newspapers and magazines, a ritual that lasts from mid-morning to mid-afternoon, while ma’am writes in a notebook or busies herself with the iPad.

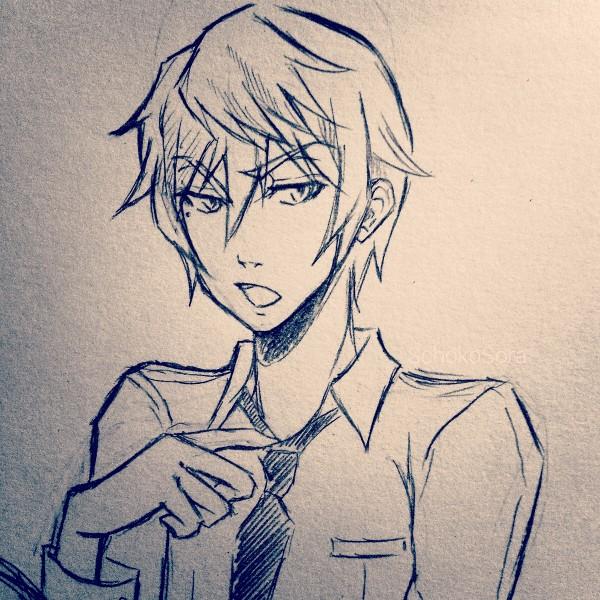

The grandson is the tallest person the gardener has ever seen. He has tremendously long legs, the kind of legs in superhero movies. When the grandson stands by his grandfather, his grandfather’s head aligns with his chest, as if bringing attention to the words in bold letters on his shirt of the day, the only article of clothing the grandson cares to change: “Cool Dude”… “Stud” (with an image of a muffin beneath it)… “I put the STUD in bible study”… Although a third-grade education has enabled the gardener to read the words, their meaning is lost on him. Sir and ma’am have no reaction to his shirts. However, they do pick on the grandson about his hair, which in five years has undergone an array of styles from a military cut to a Mohawk to anime long with fringes. Occasionally, he would wear a hair clip or a barrette. His grandparents would comment on this. From their mixed facial expressions of disapproval and amusement, the gardener surmises that their comments must not be favorable but good-natured. In response, the grandson would smirk a cocksure smirk and shrug his shoulders.

Image courtesy of cuded.com

Today his hair is a black explosion of curls bunched up by a headband. He is in the garden, in running shorts and sneakers but no shirt. A laptop is on the grass. A voice emitting from the laptop directs exercise instructions to the accompaniment of music. The voice is deep and heavy such as those heard in wrestling matches, and the music is sinister as if the grandson were gearing up for a shield and sword battle. Within seconds, the grandson drips sweat as he sprints in place then drops to the ground and does pushups. For many minutes, he alternates between the two. The gardener is across the lawn, trimming shrubs by a banana tree, and as he watches the grandson heave and pant, he thinks of a playful canine.

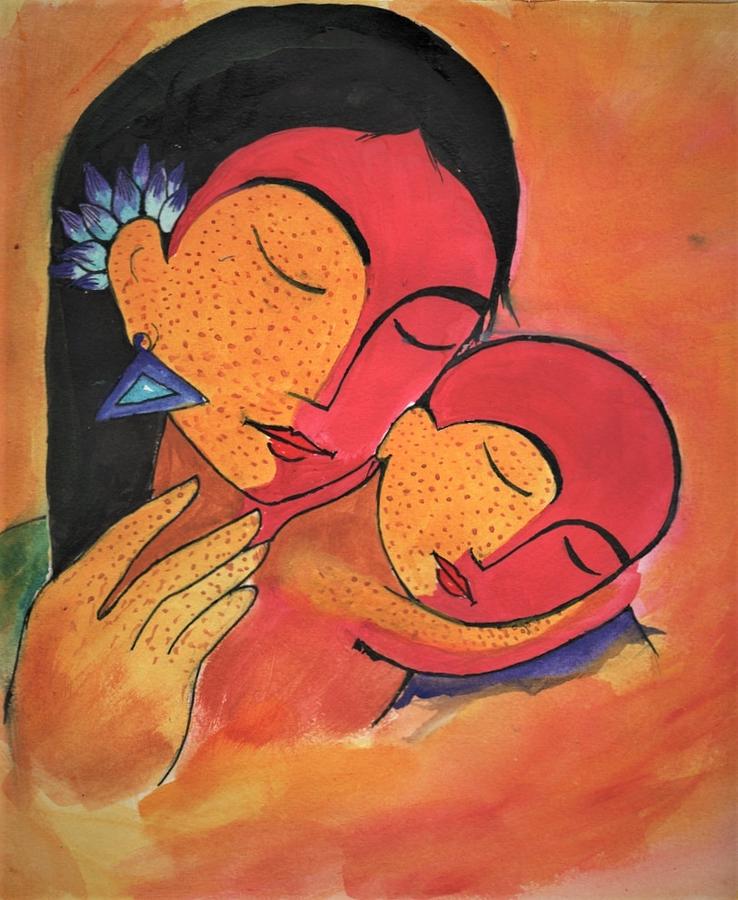

In the veranda, sir is visible through the French door on the far right. It is half-past one. He has been at the meal table for about four hours, having eaten breakfast with ma’am and lunch along with the grandson. Ma’am is at a marble table visible through the middle French door. She is arranging bromeliads, orchids, and Song of India plants in a rattan basket that she has transformed into a vase. She is in a yellow frock, though it is a very different yellow from that which the gardener associates with his mother – more a glorious sunrise than a drab sunset. The folds at the skirt are crisp like new wrapping paper, and the shoulder straps rest on flesh that is baby plump and smooth.

It is the day before Christmas. Trees are strung with gold lights. Star lanterns hang before each veranda door. A Christmas tree is inside. Though the gardener doesn’t see it, he knows it is there because he carried it in. The tree stands against a wall in between two French doors, decked with gold balls and a gold star on top. Underneath, a stuffed Santa is checking his list as he sits in a rocking chair amid presents wrapped in green and red.

There are more presents than there are family members. Sir and ma’am have a son and a daughter. The son has three children of his own, two in their early twenties and one in high school. The daughter lives in another country and comes home for the holidays. As far as the gardener is aware, she has no family of her own. She must be staying at her brother’s for the moment since the gardener hasn’t seen her in a few days. Sir and ma’am had another daughter, the mother to the grandson, but she and the son-in-law perished in a car crash shortly before the gardener was hired.

The serenity is a contrast to the atmosphere of five years ago. Upon his arrival, the house help hadn’t told the gardener of the tragedy. Even so, he sensed a great loss in the family. Ma’am’s smile on the afternoon she met the gardener wasn’t quite a smile as much as it was a mask. A friend of the family had recommended him. He and ma’am were just outside the veranda. Her face was fair, rarely touched by the sun, and her dress, creased rather than the creaseless condition of all her attires thereafter, was patterned with gray silhouettes of doves, as if the actual birds were trapped in their own shadows. As the gardener spoke of his skills, ma’am stood attentive, hands clasped together and eyes fixed on him, yet she didn’t seem to see him. Neither did she seem to hear him. Darkness shaded her eyes. Everything around her grew heavy – the permeating silence, the heat, the tic toc of a piano clock. What a waste for sadness to fill such a lovely home, the gardener thought.

Image courtesy of i.ytimg.com

The garden itself was a mess of unruly ferns and wild turf. Perhaps ma’am sensed the suffocation, too, for one of the gardener’s first chores was to prune flowers and plants for her to arrange, and what exuberant arrangements she created – flora and fauna sprouting from porcelain vases as water does from a fountain. Sometimes, she would include tree branches with chicos dangling from them, the tiny brown fruit sweet as nectar ripe for the picking. She’d be working at the marble table in the veranda. In house dress and slippers, brows furrowed and eyes squinting in concentration, ma’am would snip off extraneous leaves and twigs with the meticulousness of a surgeon. And just like that, the heaviness lifted, one snip after another, week by week. Soon, she requested the gardener to carry in pots of plants.

The first time the gardener entered the house, he thought he had been transported into another universe. Never before had the gardener been in the midst of mind-boggling splendor. Ivory carvings of Chinese deities; dining table seats upholstered in brocade; oil paintings that romanticize his own farm existence, the crop lush and farmers youthful with unblemished faces… where do such untouchable things come from? He had never stood on a carpet. Now a Persian carpet was caressing his soles. He felt as though he were one with the woven flowers and birds that filled every space of a dreamlike cage. No, no, no, one of the maids whispered to him. He must never set foot on the carpet, she told him and flipped the edge of the carpet over to allow for ample floor space.

That was when the gardener first saw the grandson. The young man’s presence startled him, for he was unaware until then that a grandson exists, and he had already been here a month. The grandson was walking down a staircase that faced the living room, directly toward the gardener. He was thin and hunched with a sallow face and disheveled hair. His jogging pants were loose, and his black shirt was oversized. He appeared to be in deep thought, negligent of his surroundings and unnoticing of the gardener. Just as he reached the last step, he went back up, where behind a closed door, he lost himself to video games.

The grandson remains a video game fanatic to this day, only now, shirtless with face to the sun, he has become a part of the world. The gardener is glad for the grandson; he would be glad for anybody who has gotten over a great loss. He can pinpoint the precise moment when the grandson emerged from the shadows of his room. On an afternoon amid ma’am’s mission to resurrect the house, ma’am excused herself from the meal table and returned minutes later with the grandson. She persisted with this pattern for a number of days before designating a maid to summon the young man, until the habit of joining sir and ma’am for lunch had been instilled in him. The grandson’s current exercise regimen has been a weekly routine for the past several months; six months, the gardener surmises. In this half-year span, the grandson has developed muscles and a ruddy complexion. He also hums songs and plays the piano in the veranda. The music that at last fills the house has the rejuvenating effect of rain after an interminable drought.

Image courtesy of shutterstock.com

That mourning could last for years befuddles the gardener. He isn’t quite sure he knows what mourning even entails. Work has always been his primary thought, more so upon his mother’s death. Time goes by so fast that he seldom has the luxury to dwell over his feelings. His mother’s death itself was quick. She was fine one day, and then she caught a cold that wouldn’t go away. Regardless, she continued with what she always did: haggle at the stall, count money, wash the laundry, cook… One morning, she couldn’t get up and, for two days, lay emaciated under the Virgin Mary’s comforting stare, coughing blood, her appetite gone. She died in her sleep. She had been ill not even a month.

At least his mother left in peace, the gardener tells himself as he has been doing for the past twenty years. She had never complained, had never shown any sign of physical discomfort, so she must not have been in pain. The gardener thanks God for this. Certainly, it was a miracle that the wall on which hung the sacred Virgin’s image had been intact after a typhoon hit just months before he lost his mother.

Have they ever experienced a miracle? the gardener wonders of sir and ma’am as sir sits at the meal table and ma’am arranges flowers. A pity if they have not. He wishes they would before age takes its natural toll. One thing he is sure of is that sir and ma’am will never lose this home. Through typhoons of the past years, cables have snapped, electricity has died, and lightning struck a hole in the driveway. And yet, no windows have ever shattered, no door has ever been unhinged.

What is particularly extraordinary is that the gardener has never noticed a religious effigy among the valuables to protect the house, whereas with his home, on the last typhoon his mother would experience, the ceiling collapsed and walls fell despite the Madonna. The devastation would have been a horrible memory if not for what happened next. At daybreak, the gardener’s mother was outdoors to salvage their possessions, among them a broken picture frame that contained a photograph of maternal grandparents he never knew, tin cooking ware, and a stuffed bear gifted to him and his siblings by missionaries one Christmas, its fuzz soggy and smile mud smeared. She was a lone figure in a yellow frock amid trees and grass glimmering green. Her face as expressionless and sharp as a bust carved from rock, she piled their possessions by the trunk of an uprooted mango tree. As the family joined her, she led a prayer of gratitude that the tree had not crashed on their home. The sacred Virgin was indeed watching over them, she declared. Raising a tin pan to the heavens as if it were the crucifix, she instructed father and children to return their belongings inside. This was her way of ordering to cry none and to rebuild. The gardener swallowed his tears and did as told. The tears saltiness stung his tongue.

Gazing at the sky, a luminous blue canvas of explosive clouds, the gardener sees his mother as if this sky were the very sky that welcomed her the morning after the typhoon. He sees her everywhere.

Image courtesy of cdn3.volusion.com

From the marble table in the veranda, Ma’am faces the garden. Absence of makeup notwithstanding, no matter the jowly chin and cheeks, she exudes a youthful aura. What she lacks in alacrity, she compensates for in her attentiveness, for attentive she is to sir’s every need. Over the years, through sir’s increased crippling arthritis, her alertness has become a sixth sense. She knows before sir himself utters a word when he wants to stand or needs to use the restroom. They could be engrossed in their activities at the meal table when, suddenly, ma’am would ring the bell for a maid or summon the grandson or the gardener to assist sir even while he’d still be flipping through the papers.

Couples long married must be able to read signs, muses the gardener. His own wife has a telling gesture of raising one eyebrow when in disagreement, both when in agreement. She could lie, yet those eyebrows would reveal the truth. Once, he sprinkled brown sugar on her rice cake and asked if that was alright, at which she responded yes with her left eyebrow arched. He grimaced, gave her another slice free of sugar, and they laughed. The gardener’s laugh was a whoop and a holler, his mouth open wide, which is rare of him. He hardly shows his teeth. So embarrassed is he of their grayness and of the space where upper front teeth should be that he scarcely smiles. But his wife doesn’t care that he has bad teeth, and whenever she is around, neither does he.

With a hand wave, ma’am motions for the grandson to come near. He positions himself behind sir’s chair and pulls it back as sir clutches the bamboo arms to stand. Sir then takes hold of the walker and proceeds to the garden. He is dressed in golf shorts and a red golf shirt. Chair in hand, the grandson scampers ahead of his grandfather. He sets the chair down near the spot the gardener has been working at, a few feet away from the shade of a banana tree. The gardener knows that sir wants to sit in the sun, so he rushes to the veranda, where before entering, he removes his slippers and wipes his bare feet on a mat. From the meal table, he takes a chair out for sir to rest his feet in. When sir resumes his seat, the gardener assists him to raise his legs, one after the other, onto the chair cushion. Sir’s legs are thin and alabaster smooth with knees swollen to the size of water balloons.

Returning to his exercise regimen, this time one with a series of stretching poses, the grandson leaves his grandfather alone with the gardener, who tends to a patch of bromeliads in bloom. The gardener sowed their seeds two years ago, and he thrills at the vision of sunrays rising from the soil. He wants to share his happiness with his wife and daughter. His daughter is five and in kindergarten, with curly hair and eyes big and brilliant as if she absorbs to memory everything she sees. He imagines the delight in his daughter’s eyes as she touches the petals, her mind functioning at the speed of a timer to study the color, the texture, the beauty. But his wife and daughter are both far. He cannot afford a home in the city close to a school, and his daughter must be educated so that she could go to college someday. This is the gardener’s dream – a college degree for his child. She would be the first in his family to boast such an achievement.

Image courtesy of https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com

For a moment, sir watches his grandson. The grandson is in a steady pose with left foot on the ground and right leg in mid-air behind him. He is grabbing onto the right leg by the ankle so that the foot is parallel to his back. He holds the pose for several seconds before switching his balance from one leg to the other. Sir smiles slightly. It is a tender smile, one that seems to carry with it a wave of memories. He then lays his head on the back of his chair and shuts his eyes. Under the sun, his face is radiant.

Two maids appear in the veranda, one with a tray and another with a mini side table. They walk with precision towards the garden, until ma’am stops them and takes the tray. As the maid who remains sets the table next to sir, ma’am places the tray on the table then caresses sir’s cheek. He opens his eyes and winks at her. She giggles. Sir’s gesture and ma’am’s reaction warm the gardener. It even makes him feel that his presence might be an intrusion, for he has never witnessed such youthful flirtation between the two. A vision of himself and his wife in old age frisky in the same manner flashes before him, and… softly… he also smiles.

The tray contains a glass of coconut juice and a bowl of peanuts. Together sir and ma’am each eat a peanut then another and a third before ma’am returns to her flower arrangement. Wincing at the thought of the peanuts’ saltiness, the gardener puzzles at sir’s and ma’am’s hunger for it; both seem to savor the saltiness as one does water on a hot day. Peanuts in hand, sir continues to toss one peanut after another into his mouth then gazes at ma’am, his eyes mirthful with a mixture of adoration and gratitude. They have been married for sixty years, six decades of shared joys and sorrows, and here they are, young lovers at heart.

The gardener gets the impression that if sir were to die this instant, he would do so a happy man: he has mastered the art of survival. This is not an opinion as much as it is a well-known fact. A year ago, a woman came to interview sir in the veranda. She was young and slim, in a purple dress suit without a wrinkle, a detail which no doubt must have pleased sir. He is a stickler for appearances and was himself in coat and tie and a shirt stark white. The gardener watched the interview in the maids’ quarter downstairs when it eventually aired on TV. While proud of the lush foliage in the garden background, he was especially intrigued by the story being told. At the age of five, sir lost his father to a heart attack and, to assist in the family income, started work as an aid to fishermen. He grew up in a port town, where rocks demarcated paved roads from the beach and fishermen set sail at the last crow of the rooster. Sir’s payment was one fish. Meals were always later than the norm, for he would assist his mother as she knocked on neighbors’ doors for scraps of leftovers. His mother was a stoic woman, a woman who seldom smiled and who wore a hair bun atop her head as a queen does a crown. Her income as a seamstress got sir through school. Succeeding jobs for him consisted of cigarette street vendor, newspaper boy, waiter, and bank messenger. Sir’s dream was to have an air-conditioned office with a desk. A knack for numbers elevated him to the position of a teller. Over the next forty years, he would report to work at a floor higher than the previous position held until he was at the very top, owner of his own financial institution. His dream changed, as well – to give his children what he never had, a full meal every day, at any moment of the day. That he had fulfilled this most ardent wish many times over buoyed him when he was at the lowest point of his life, the loss of a daughter. Although he shall grieve his daughter to his own grave, that she died assured of a father’s love has given him the strength to endure. Sir’s philosophy: to be successful and happy, one must face… rather than deny… the cruelties in life with a conquering spirit.

Image courtesy of encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com

Greatness manifests in different ways, the gardener ponders. Sometimes, it is loud, trumpeted in print for all to read and on TV for all to behold. Sometimes, it is quiet. For all sir’s publicized accomplishments, the gardener is most in awe of his private generosities. The gardener’s room by the garage is the nicest room he’s ever had. The walls have no cracks, and a glass shade covers the ceiling bulb. The gardener is never hungry. Every weekend, the cook is given ample allowance to stack the helps’ kitchen with any food they want. Because he hails from a different region from that of the three maids and two chauffeurs, some of the dishes have been a first: tiyula itum, for instance, a medley of ginger, coconut meat, and turmeric in a black broth so hot and spicy that the flavors sear his tongue. This is what dining in a restaurant must be like, he imagines. But the true testament of sir’s magnanimity is the support sir extends to children of the help. The laundry maid has one boy in high school and another in college… an engineering major, no less… and all thanks to sir, who funds their tuition.

Sir also provides for the gardener’s little girl, and this the gardener reminds his wife of when, during his bi-monthly visits, she bemoans his distance. Occasionally, he wishes that he had the means to cover for his daughter’s kindergarten expense in addition to a bit of extravagances. How nice it would be to buy his wife a wedding ring and his daughter a doll with a dollhouse, to spend a day with them at the mall, sampling delicacies in the food court then promenading on the rooftop garden, and to watch a movie in an air-conditioned cinema as his daughter chows on popcorn and hot dogs and cotton candies and imbibes juices and soft drinks. He reprimands himself for wanting too much. Isn’t it enough that he is master of this garden? That he has a roof over his head and food served to him? That he is able to give his wife and daughter a home in the province?

The bowl empty of peanuts, sir shuts his eyes once more. He is motionless for several minutes, save for the twitch of a finger and the heaves of his chest. Though he is not asleep, he appears to be dreaming. Or perhaps he is reminiscing. Indeed, what memories sir must have. That he started life penurious does not astound the gardener. The gardener regards sir’s rags to riches tale as possible solely to others, for his relations with sir have exclusively been with the man as he is today – a celebrated banker, a millionaire – and nobody the gardener knows, be it family or neighbor, friend or acquaintance, has been blessed to rise to such heights. Since he has neither witnessed nor experienced the toil of aspiring towards a goal equivalent to a king’s ransom, he believes the ransom is reserved for a preordained few. The gardener has the urge to ask sir why some men are chosen to be great and why others are destined to remain the common man, only to instigate a conversation on a subject outside his duty as gardener would be inappropriate.

As though suddenly aware of a matter of dire importance, the grandson requests sir’s attention to music he plays on the laptop; he has taken to song-writing once again. Good, his grandfather says and gazes at the young man with a look redolent of the future. The song is in English. From what the gardener understands, it is a song about a man fallen and alone as he seeks solace in memories of a lost love:

Image courtesy of images.fineartamerica.com

Since you’ve been gone, I’ve been down, adrift in a wasteland, trying to find meaning in all that now exists in my head. The past must mean something, a link somehow to what is yet to be.

The grandson replays the song a few times. Upon the third listening, the gardener concludes that the lost love could very well be that of a mother. All these years, the gardener has sought to rekindle that love. Every seed the gardener plants, every tree he prunes and flower he nurtures, is in memory of his mother. Making things bloom and flourish keeps her alive, and with her spirit that emanates from each sprouting of a leaf, the gardener’s will to give the best of who he is and what he has to his daughter grows ever stronger.

The gardener is aware that his devotion is common of every father, but his daughter is no ordinary child. She has a skill for drawing; art is her own method of cultivating life. As vivid as the memory of his mother is, the gardener has difficulty describing her physically. Words that come to him are in praise of his mother’s character, which his daughter has captured in images of a cloud that haloes a mountain crest, sunshine through bleak skies, and a tree a wealth of birds and foliage and as indomitable as an ancient rampart… images of his own childhood. Remarkable that his daughter should experience his own past, if only in her imagination. Remarkable that these images surround him still. And at this moment, the images are taking auditory form in a song.

What a peculiar phenomenon that the grandson is unaware of the impact his music is having on one so close and yet a stranger. If the gardener were to present the grandson his daughter’s drawings, what would the young man think? What songs would he make out of them? What melodic treasures hidden within him would they reveal?

Sir asks the gardener about his daughter. The gardener is taken aback by the question. Although it is not unusual of sir and ma’am to inquire about the well-being of the help and their families, such occasions are rare for the gardener since he is seldom alone with either one. His daughter is doing well, the gardener answers. She is a diligent student, one who likes to read. Her favorite stories are by Dr. Seuss, for she adores the mischief and cleverness of such characters as Thing One and Thing Two and the Cat in the Hat. She is becoming proficient in English as a result. Sir then asks about the wife. The gardener chuckles, somewhat with pride, and says that she has put up a sari-sari store in their living room. The knick-knack she sells of peanuts, soft drinks, chips, and cough drops are a mighty convenience to the neighbors. Plus, the store makes her feel useful. Sir lauds the gardener for an industrious wife and an intelligent daughter; the gardener and his family shall surely prosper. Such a compliment from a great man overwhelms the gardener, as if sir has bestowed upon him a touch of the celestial.

And there it is… a touch of the celestial. The gardener realizes that he has been touched since the day he started here five years ago. All the choices the gardener has made in life have inevitably led to this family, all the prayers and hard work and planning. He shall never forget the sensation he felt upon first seeing the residence. The white gate beckoned him with its copper post lamps and vines coiled around the railings – a vision of heaven’s gate. At once, he knew the future would be bright. So he married a maid to a neighbor. Together, they had a child. This child will fulfill all the possibilities that the family’s benevolence along with sir’s life story have inspired. She will possess the power of knowledge to accomplish astonishing deeds. She will experience the fruition of dreams. All that she shall achieve will withstand the most cataclysmic of storms.

Courtesy of https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com

The gardener discerns magnificence, too, in the grandson. There before him, bathed in sweat and smoldering in heat, amid the music of the grandson’s creation that pervades the sunny stillness, the grandson rises anew as if from a baptism. As ma’am herself said upon the gardener’s arrival those few years ago: with the gardener comes change.

Tonight is Christmas Eve. Ma’am will be dressed in her fineries of a pearl necklace and red satin slippers. She will bring the family together. They will dine on a roast pig, a delicacy that sir and ma’am will relish the help with, as well, for this is what Christmas is about – family and giving – the very honors that they already celebrate on a daily basis because every day is a birth of sorts. So the gardener will not be with his wife and daughter. No matter because this house is where he serves them, in this garden that he dedicates his existence to keep beautiful and fertile through typhoons and blistering heat.