Image courtesy of creativeeducator.tech

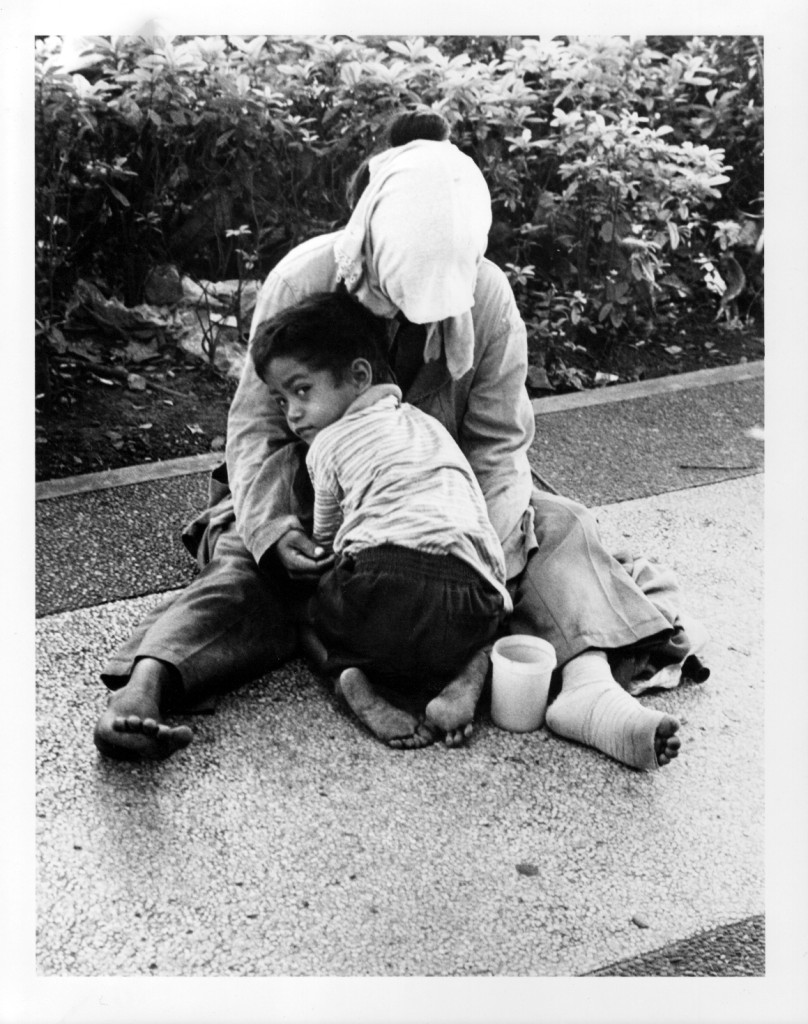

When I was four, I lived in Tokyo, in a white building that had a rooftop deck with a sundial and a swing set and where I first experienced snow. On that morning, my parents summoned my brother, sister, and me out of our beds to the winter wonderland that had formed overnight above. The vision that awaited us was new to my parents, as well, we being a family from the Philippines: a flurry of marshmallow ice balls sweetening the sky; a floor so white and soft that it seemed the world were adrift on a cloud. Songs and stories about the crystalline flakes that fall from heaven have it right – snow is lovely. I took to snow more willingly than I ever have to the sun, the coldness not a problem even though I was in sneakers instead of boots. Like newborns, the five of us gazed at and touched the whiteness around as if it were one more gift life presented. What a marvel it was to be in a scene that until then had been a mere tableau in a storybook. Since snow is real, I wondered, what else of make believe could come true?

Image courtesy of wordpress.com

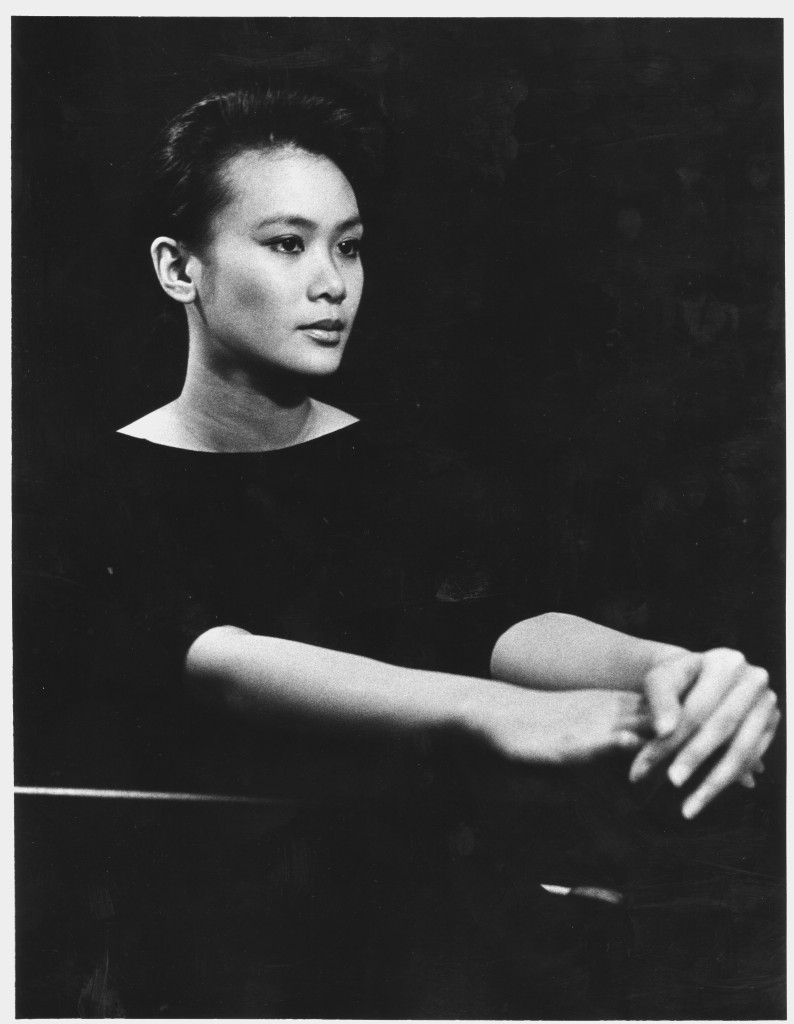

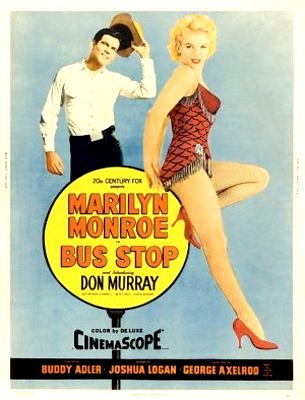

The answer was the movies, and one movie in particular that is intrinsic to our childhood: “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” (1937). Actual snow does not equate into my memory of the classic. The screening was held on a clear day at the American Club, a sporting and social facility in Tokyo for expatriates and their families. A poster of the evil queen, gold crown on black head covering and Bette Davis eyes, stood on sun-dappled ground by the entrance. In the darkness of the theater, as a face part mask and part gargoyle appeared in the evil queen’s mirror to pronounce Snow White the fairest of them all, a rush ran through me. A princess, her face as pale as the moon, trills that someday her prince will come… Hi ho hi ho, it’s off to work we go… A poisoned apple on the floor, free from the grip of a lifeless hand… A witch meets her fate as she falls off a cliff amid thunder claps and lightning streaks… Resurrection by a kiss… A castle in the sky… By the end of the film, my head was awhirl with questions about the human condition from love to mortality.

“Are you going to die?” I asked my mother. She was in the kitchen, dressed in a yellow robe and white puffy slippers, holding a grill with which she was making a pancake that we called flying saucer. They say that as children, we learn of the ultimate end at the age we enter nursery school. We learn from cartoons such as “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.” In princess fairy tales, death is never dignified. Death is an agonizing exit that happens to villains. Yes, Snow White is an orphan under the care of a madwoman, but if her parents’ final moments had been peaceful, we are never told. Where would be the melodrama in that? “No,” my mother said. That was all, and it was an appropriate answer. I would know the truth with age. Until then, my mother allowed me to believe that we five were inseparable forever. She took the same stance with Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy; to tell me they don’t exist would have been to rob me of my childhood.

However, my mother’s comforting didn’t silence the stuff I envisioned. Although all kids have an imagination that runs wild, mine would have made El Greco and Ingmar Bergman proud. Death was skeletons in black cloaks, the sky gray as they wallowed in a pit surrounded by barren trees and parched earth. I would lie on my bedroom floor, where I’d shut my eyes and hold my breath. So this is what it is to be dead, I’d think. Blindness became another one of my curiosities, though I doubt it was Disney induced. We’ve got Disney characters who are handless, wooden, sneeze ridden, and goofy, but none who is visually impaired. I would wander the living room with eyes shut, my arms outstretched in front of me. That came to a stop when my mother caught me and noticed a bruise on my forehead from my having bumped into a wall.

However, my mother’s comforting didn’t silence the stuff I envisioned. Although all kids have an imagination that runs wild, mine would have made El Greco and Ingmar Bergman proud. Death was skeletons in black cloaks, the sky gray as they wallowed in a pit surrounded by barren trees and parched earth. I would lie on my bedroom floor, where I’d shut my eyes and hold my breath. So this is what it is to be dead, I’d think. Blindness became another one of my curiosities, though I doubt it was Disney induced. We’ve got Disney characters who are handless, wooden, sneeze ridden, and goofy, but none who is visually impaired. I would wander the living room with eyes shut, my arms outstretched in front of me. That came to a stop when my mother caught me and noticed a bruise on my forehead from my having bumped into a wall.

As for love, this was an intangible subject, more a feeling than an image. Because of the security family provided – occasional after school surprise gifts from my mother (a box of clay, pez sticks), my father’s piggy back rides, sharing stickers of scented strawberries with my sister, and evenings in my brother’s room as he’d build models of war tanks while I nibbled on the styrofoam packaging the parts came boxed in – I never questioned the feeling. Those moments were the norm. “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” offers its own semblance of normalcy that reproduced my own. Animals flock to our heroine as birds do to a nest, and little people who reside in a cottage around which flowers are in bloom and the grass is green look upon her as a mother. Love is a song and dance, the tweeting of birds, and a smile that squashes all things troublesome. What I already had required no imagining.

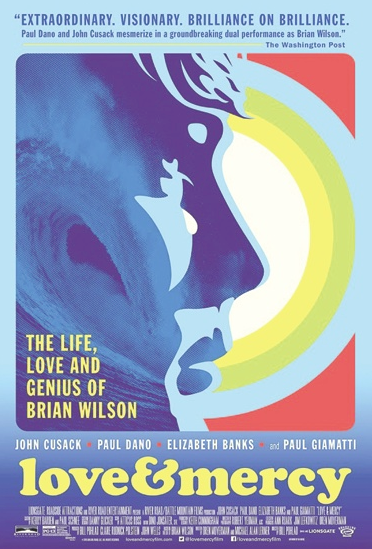

Image courtesy of pinimg.com

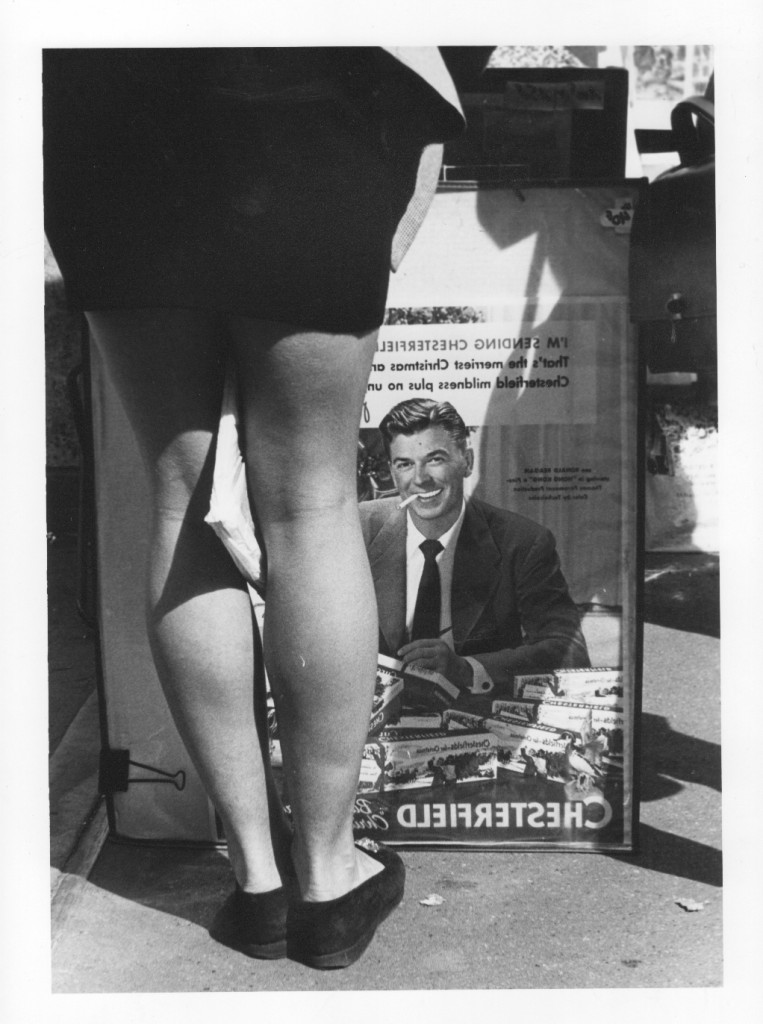

That is with exception to the prince. As grown-up as we become, the concept of a mate born for the purpose of someday intertwining his or her destiny with our own remains. The union is called marriage. My sister had a husband who lasted for a mere two years. “I married him for all the wrong reasons,” she said. Those reasons included wealth and luxury. Beneath the comfort, she might have known immediately upon tying the knot that divorce would be imminent. Already I had detected friction between them when I accompanied her to decide on which of his furniture to keep for the house they were to move into. “That’s ugly,” she’d say of a vase. “It’s expensive,” he’d rebut. Then she’d turn to me and ask, “Don’t you think it’s ugly?” My sister-in-law was involved in another conversation in the aftermath of my sister’s separation from her husband, and her input was that a partner could be a disappointment when endowed with a potential that he or she exerts minimal effort to achieve. A discussion followed on the ideal match, the circumstances under which relationships form, and the redefinition of Mr. Right in accordance to a stage in life, terminating with both women stating, “Mommy was lucky to have found her Prince Charming.”

Indeed, “lucky” is the best word to describe the outcome of the dice my mother rolled in her selection of a husband, a factor that is absent in fairy tales. She made a gamble at 22 to marry my father, a bank clerk with high goals, over suitors established in their financial standing. In “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” true love is preordained. Certainly, my parents have had their rough patches – disagreements over expenses and insecurities over fidelity, typical issues that arise in the course of being together for nearly 60 years – yet together they are. The reality of a fairy tale is that while it shows the magnificence of a meeting, “happily ever after” is open to interpretation. Notice the trials Prince Charming duels with in order to reach Snow White. Even in a story with a predictable outcome, conflicts abound, all as innuendo that the castle in the sky offers its own set of challenges for husband and wife to overcome so that happiness can prevail to the grave.

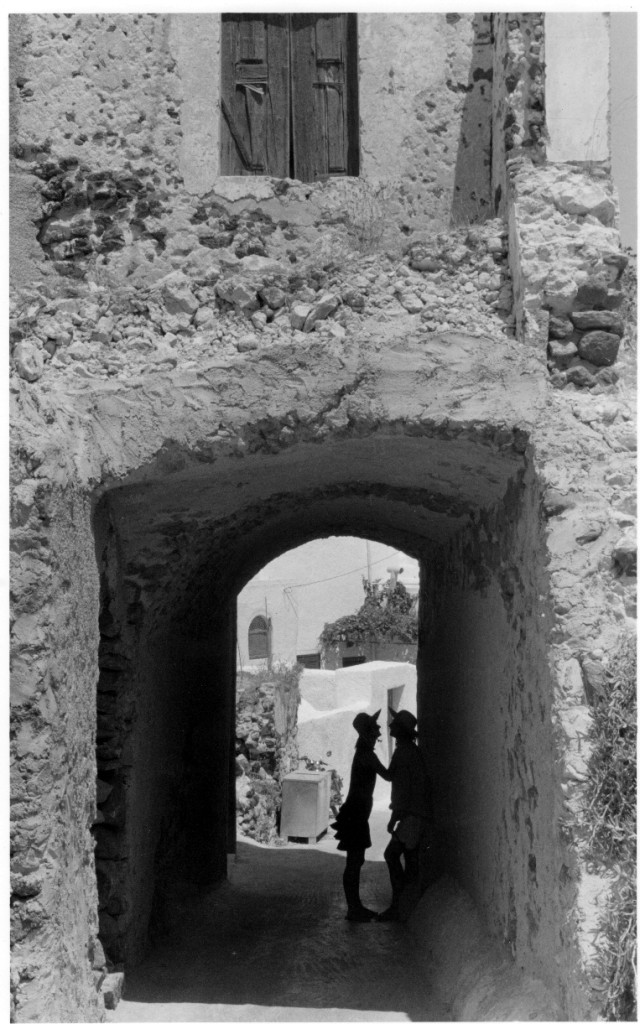

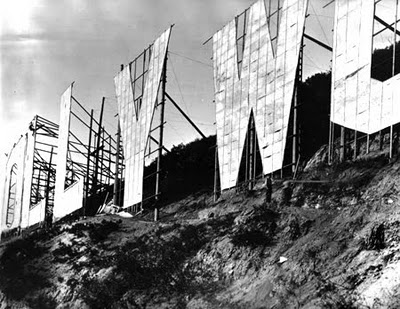

Image courtesy of static.guim.co.uk

Call me a fool, but I continue to believe in fairy tales. “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” has more verity than we’d like to acknowledge it for. Life is a cycle of evil queens and losing our way in a forest, of poisoned apples and suffering a form of death. And out of the woodwork, someone comes to our rescue. Although the person may not always be Prince (or Princess) Charming, that a savior appears when least expected yet most needed give us hope that someday… someday…