Image courtesy of i.ytimg.com

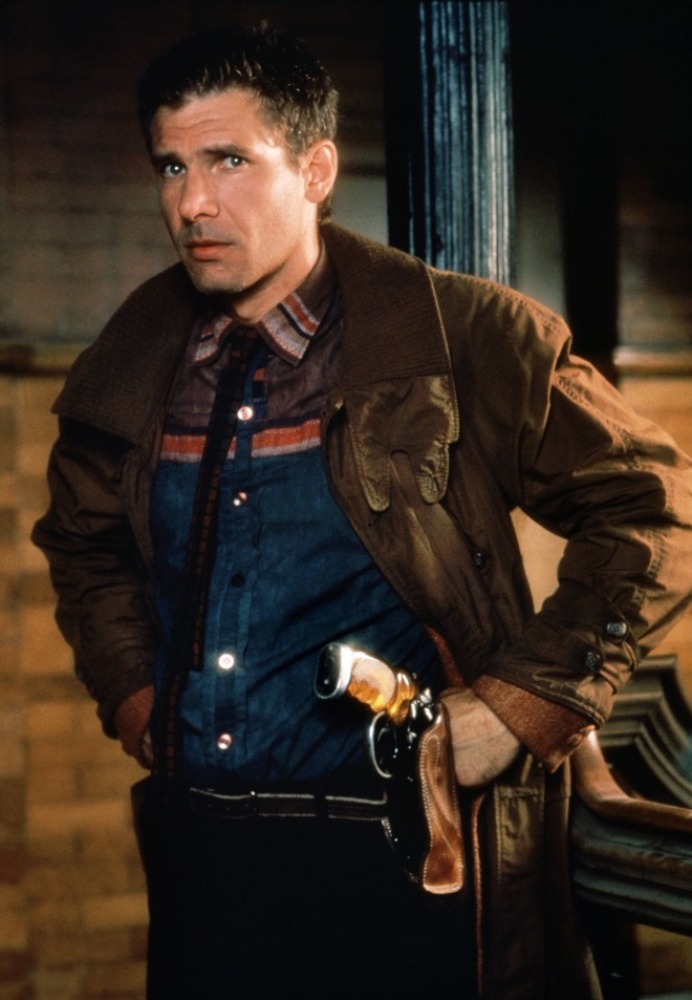

Everybody knows the tale of “Romeo and Juliet” (1968). Even if you have never read a word of William Shakespeare, and even if you have but find his prose too archaic to comprehend (that would be most of us), you know it. The shared grief of a boy and a girl, who sacrifice their lives on the altar of love, set the standard for every romantic tragedy to follow. What is curious about the movie adaptation of literature created four centuries earlier is that it would be made and be a box office success in the decade of the 20th century that experienced the apex of rebellion against the past. History attests that no ten years revolutionized our advancement as citizens of the world more than those of 1960-1969. A minister’s dream of human equality upended a long-standing tradition of racial segregation. Women were no longer divided between the titles of Miss and Mrs., but united as Ms. Gays and lesbians broke through closet doors and into the light of freedom. Indeed, times were a changin’ with such velocity that men grew their hair, joined hands with those they once held subordinate, and sang in harmony against the destruction in Vietnam. Make love, not war was the motto of this era. Every man was a Romeo. Every woman was a Juliet.

“Romeo and Juliet” is loyal to cinema’s mission in that it is a mirror of the cultural and social milieu in which it was made. As unforgettable as the ultimate pact of union is that forever links Romeo (Leonard Whiting) to Juliet (Olivia Hussey), life more than death suffuses the movie. It’s gorgeous to watch. Costumes the colors of Jupiter against a Renaissance backdrop evoke the murals of Michelangelo. Juliet and her Romeo are as dewy as the moon under which they seal their devotion. Energy thrives in every scene. Dueling swords aside, we can’t believe these young Capulet and Montague rogues truly want to off each other. Both sides are at it more like rugby players fighting over a foul than like warriors. And the balcony courtship – all sighs and kisses and hugs – burns with the fire of two people hungry to be one.

But the most mesmerizing moment is the dance where Romeo and Juliet first lock eyes. This isn’t a meeting. This is a collision. We could almost visualize two chariots racing towards one another, the horses maneuvering them at full throttle. Destiny has no brakes. Neither does disaster. Who cares? It feels good to be flying against the wind, unstoppable and free.

Image courtesy of images4.fanpop.com

In this scene, Romeo sneaks into a Capulet gala. He masks his face to conceal his identity, though he fails to conceal his handsomeness. His figure is lithe. His eyes are visible. They gleam with such admiration that Juliet is beguiled. For the pair, the world stops. The only person in motion is the other. They circle the room in a merry-go-round of seduction, catching glances over people’s shoulders, through the space in a crowd. She is coy and courageous. He is determined and daring. When at last Romeo, from behind a post, grabs Juliet’s hand, we know that in this single touch, they have discovered the purpose of their existence. Time melts into Juliet. She can only stand frozen, throw her head back, and shut her eyes in awe as the past and the future converge in this one sensation. Romeo reveals his face, smiling and smitten. She studies his beauty as though she had just unearthed a holy relic.

Director Franco Zeffirelli hit the jackpot with Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey. Whiting is just 17 in the film. Hussey is 16. They speak Shakespeare with the fluidity that we text messages. Perhaps this kind of language is inherent in the Brits. Regardless of how old the tale of “Romeo and Juliet,” Whiting and Hussey bring it to life with a youthful freshness.

Image courtesy of peoples.ru

We are inclined, as a result, to believe that “Romeo and Juliet” is about the young and for the young. Not so. Let me tell you the true story of a Kentucky boy on the dawning of the Depression who dreamed of movies and movie stars. In 1928, Hal Riddle was 11 years old when he fell in love for the first time. The object of his emotional awakening was the lead actress in a film called “Adoration” (1928) – Billie Dove, a diamond-studded Howard Hughes paramour on whom, during the peak of her fame, the public stormed with 50,000 fan letters a week. The boy’s mother was not pleased as he announced his love for Dove when he came home that day. This meant he had played hokey again. He wrote Dove a fan letter, and in return, received an autographed photo. It would have ended right there, but Riddle himself wanted to be a movie star, so when he grew into a young man, he went to Hollywood. “Cinema Paradiso” (1988) could have been based on Hal Riddle. (http://www.rafsy.com/films-1960s-1990s/cinema-paradiso-the-sacrifice-behind-a-dream/)

You might recognize Riddle in the Michael Keaton film “Johnny Dangerously” (1984). He plays a prison warden. He had been working as a character actor for 40 years, but had never achieved the stardom he had yearned for back in Kentucky. “Johnny Dangerously” was his last shot. Alas, it was not meant to be. Calling it quits, Riddle later took up residence at the Motion Picture & Television Fund’s Wasserman Campus in Woodland Hills, a retirement home for the elderly who play a role in Hollywood’s history, whether big or small. He must have expected the rest of his life to consist of nothing more than bridge, golf, and swapping with fellow residents anecdotes about dreams that were never fulfilled. But that would not entirely be the case because it so turned out that Billie Dove was in a facility a mere five-minute walk away from his cottage.

Although Riddle might not have become a star, one dream did come true. The famous actress for whom he held a torch for nearly all his life would love him back. It didn’t matter that Dove was frail and wheelchair bound. As he confided to Entertainment Weekly: “… when I looked at her, I still saw the actress in the photo she’d sent me when I was a kid. I just saw Billie Dove. And I could see the essence of her beauty still.” And radiant she had been: black hair against white skin, curled lashes, and lips the red and succulence of a heart.

Image courtesy of i.ytimg.com

Through age, ailment, and dashed ambition, the Romeo in Riddle had not dwindled. A bystander at the community movie theater who had overheard Riddle gush to a friend about his boyhood crush brought him and Dove together. He was 79. She was 93. He told her everything of his life, including her autographed photo that hung on his wall in every place he called home up to that moment and to the end. When Dove died on New Year’s Eve 1997, a year after she and Riddle had met, Riddle delivered her eulogy. He lived on for several years more, fueled by a passion to tell the world about his two greatest loves: movies and Billie Dove.

This is why we need stories. Stories are our history. We remember Romeo and Juliet not because of their death, but because Shakespeare immortalized them with words and Zeffirelli with images. Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey are thus frozen in adolescence, in the bodies of our most famous couple – both permanent reminders of what is possible in us, whether young or old. We can say the same for Hal Riddle and Billie Dove. That the two were not teens nor are familiar to all is irrelevant. Riddle’s public appearances in the wake of Dove’s passing paid off.

Their love is everlasting on the internet.

Image courtesy of rikaturel.com