Image courtesy of m.media-amazon.com

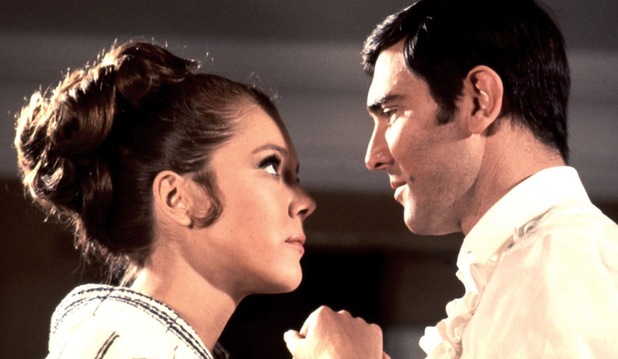

“When the devil cannot reach us through the spirit, he creates a woman beautiful enough to reach us through the flesh.”

The temptress imputed above is Greta Garbo in the motion picture that catapulted her to international renown, “Flesh and the Devil” (1927). She is Felicitas, a countess who seduces to her boudoir a soldier on furlough by the name of Leo von Harden (John Gilbert). The tryst results in the death of Count von Rhaden (Marc McDermott) in a duel between husband and paramour. As Leo is recalled to duty, he promises Felicitas marriage upon the completion of his service, only for her to give her hand to his best friend, the irresistibly rich Ulrich von Eltz (Lars Hanson). Leo is pissed; however, not for long because no man is immune to the wiles of Garbo, and this puts him in the position of Judas to his childhood blood brother. “Aren’t you afraid of what she may do to you a second time?” the family pastor (George Fawcett) asks Leo, though not before his warning about Satan’s legerdemain to possess a man through the groin. Leo does not answer. He doesn’t care.

We, too, are speechless and in heat, no matter that it is now the 2010s. The media’s remembrance of Greta Garbo upon her passing in 1990, 49 years after she had renounced Hollywood to become history’s most famous recluse, already assured her place in the galaxy as an indestructible star. “She’s sexy,” a friend said with the excitement of a teen presented a Porsche. He was 40. “She has boobs.” I was in Paris for my second year, having returned after my junior year there followed by my final term back at Tufts University to get my degree. Since the French have a high regard of film actors as artists, the attention given to Garbo was such that she might as well had been a national hero. “Queen Christina” (1933) was the tribute film aired on TV and the one which caused Quito to gush. As the title character, Garbo in 17th century negligee, an Adrian creation of chiffon that silhouettes her mannequin lankiness, walks around a chamber, gazing at and caressing a bedpost, a spindle, a painting as if they were parts of a lover’s anatomy. “I’ve been memorizing this room. In the future, in my memory, I shall live a great deal in this room,” she sighs to the man (John Gilbert) to whom she has surrendered her heart. “How romantic,” Quito said.

/033000004026-37%22x13%22-Masters-Panoramic-Art-Print-The-Rest-By-Pablo-Picasso.jpg)

Image courtesy of groupon.s3.amazonaws.com

The most iconic moment is the last, that close-up of Garbo as she stands at a ship’s aft, hair windswept, unflinching eyes focused on the distance. A bar in Paris had a wall of TV monitors featuring news announcements from different countries, in different languages, of Garbo’s death. All ended in synchronization to the actress’s image in the conclusion to “Queen Christina.” The camera adored her. The press in her heyday had nicknamed her “The Face.” The face aged splendidly. My French tutor said of Greta Garbo that she had a look recognizable in the present, be it on the street or on the metro, at the Champs Elysees or at the Garnier Opera. We were perusing a Garbo memorial issue of Elle magazine. Garbo in beret, Garbo in flapper hat, Garbo in a bob… in every photograph, the woman exuded the timelessness of style.

Nobody could have predicted during the making of “Flesh and the Devil” the legend the Swedish Sphinx would become. When she had arrived in Hollywood, MGM didn’t know what to do with her. Studio head, Louis B. Mayer, ordered her to lose weight, scolding, “In America, men don’t like fat women.” The publicity department then promoted her as the modern athletic female before tailoring her into the archetype that would be her trademark – a European exotic, one whose sculptural features and imperial carriage conjure the heroine of a 19th-century roman à clef, an ice princess, her façade turned to jelly in the heat of passion. This anachronism was a hit with audiences, and through the 1930s, on account of America’s need to escape the Depression, her heavy accent in talkies all the more captured a hankering for romance and chivalry.

Image courtesy of ursinus.edu

Jacqueline Kennedy would be a phenomenon three decades later for a similar reason. A rare bird fluent in French, her debutante and finishing school background anomalous to the average American, Mrs. Kennedy was initially considered a liability to her husband while on the campaign trail. But he won the presidency, and as first lady, she touched the public as youth and class personified, an ideal that young women could look up to and young men could hope for in a wife. No need for a European import. That Jackie was one of us made America believe that this land has its own monuments to parallel the Neuschwanstein Castle.

Now for a real anomaly that became a hit in America, there’s the wonder called Bruce Lee. He was Asian. He was short. He fought karate. And he became a superstar. As Kato in “The Green Hornet” TV series, he so upstaged his Caucasian co-star, Van Williams, that the big screen was inevitable, all of which showcased his mastery in the martial arts. With his flying fists and killer kicks, Lee singlehandedly destroyed pervasive Asian stereotypes of geek and pidgin English speaking Charlie Chan types who spout fortune cookie phrases. “Always be yourself,” he once said. “Express yourself. Have faith in yourself. Do not go out and look for a successful personality and duplicate it.”

Garbo and Jackie themselves lived by this creed, surmounting detractors to rise above the crowd as originals.

Image courtesy of pinimg.com

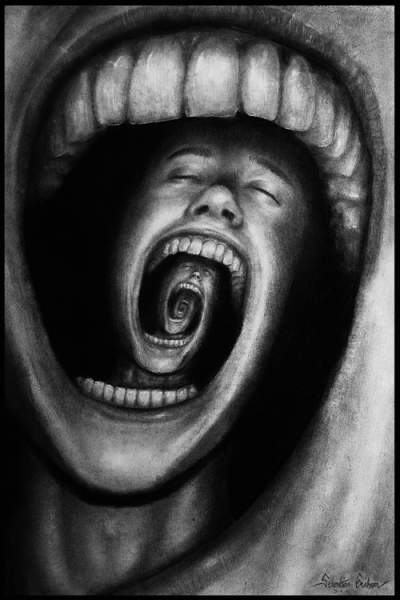

Here is another Bruce Lee dictum: “One does not accumulate but eliminate. It is not daily increase but daily decrease. The height of cultivation always runs to simplicity.” This sums up a large part of Greta Garbo’s enigma and that of Jacqueline Kennedy, as well. Garbo never attended any of her film premieres, granted few interviews, and eluded the paparazzi, donning dark glasses just as her first lady counterpart would later do, she whom Oleg Cassini, a former Hollywood couturier, dressed in clothes of pure lines and zero ornamentation to create the aura of a silent screen star. Neither woman is notorious for excess. On the contrary, their reticence and minimalism so piqued our imagination that we will forever wonder what they truly thought of themselves for all they had witnessed and experienced as crucial players in some of the 20th century’s defining events.

Sealed lips can certainly be a virtue. How often I have been told to refrain from loquaciousness. Readers would rather decipher the emotions transmitted in a story rather than to be told what to feel. It’s like love. Love can’t be forced on us. Love grows in the way a budding flower is nourished to bloom. This is why Greta Garbo is unforgettable. In a single blink she conveys love’s essence, and we are transfixed.