Image courtesy of wpengine.netdna-cdn.com

It was beauty that killed the beast. The monster in reference is “King Kong” (1933), a 24-inch model made of rubber, rabbit fur, and aluminum. Never in our worst nightmare had we imagined that a toy gorilla the height of a table lamp would tower over the Manhattan skyline. His every footfall smashes thoroughfares, and his roar deafens with the blast of the A-bomb. Kong turns Fifth Avenue into a war zone. Bravo to the feats of special effects, which augments in importance as our fuzzy menace scales the tallest building in the world. This is no mere pageantry of destruction. Kong is in love. The creature that has pierced his soft spot is a human female, blonde and beautiful Anne Darow (Fay Wray). Kong really doesn’t mean any harm, only a crew of movie people has abducted him from his island habitat, battling head hunters and dinosaurs in the process, and in man’s hunt for the green demon, it has transplanted him to New York, where bejeweled ladies and gentlemen in black tie cash in to behold the reigning monarch of jungle vines belittled in shackles. Movie people, I tell ya.

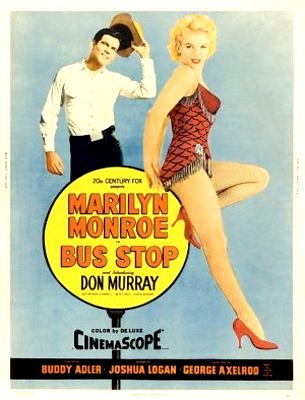

Image courtesy of allpostersimages.com

What a cycle of exploitation “King Kong” is. The spear throwers kidnap Anne in the darkness of a foggy night from the ship where she lies asleep. As Kong’s bride, she’s tied by the wrists to a pair of posts for him to snatch and abscond with into the jungle. The film men search for her. In their find, Kong becomes a prisoner. No animal rights activism here. It’s doubtful vegetarians existed in the 1930s with the superfluity they do now, and with America entrapped in economic turmoil, audiences needed to witness a beast onto whom they could vent their frustrations tumble from the highest peak. Some things haven’t changed. We still have an affinity for monster flicks, the show of us humans toppling a giant, whether the oversized freak is in the form of a nuclear mutant by the name of Godzilla or an assembly of trucks and cars that transforms into a robot. They’re exhibitions of innovation. But none is as impactful as Kong. I feel for the ape. I understand him.

Don’t tell me you wouldn’t fight to the death for something or somebody you really want. We all need a passion. Pity those who float through life without a desire that causes a bout of chest thumping and a growl. In everyday life, we call this stubbornness. We’re born with it. As babies, we cry and thrash our limbs for a craving to be fed since we haven’t yet developed the skill of language. Then we learn our A, B, C’s. Eloquence mitigates temper tantrums. Or so we think. Our tearful pouting persists in adulthood. We’ve just trained ourselves to sublimate it. Even though we may plummet from the sky because our wings are of wax, we don’t give up. We struggle to fly. We’ve made it so high, up there with the gods, the vastness of the world our own by virtue of the vista we’ve only thus far seen in pictures, read of in books – oceans and seas the blue of topaz, mountains we can trace with our fingertips, clouds wispy as the spirit of doves gone. Higher. Higher. This is what we’ve dreamed of, worked for, sacrificed over. And now we’re falling. Shit!

Image courtesy of handyvandal.com

My father has said that I was one impossible kid. We’d be walking on the streets when I’d stop in my tracks and cry upon spotting a toy that would trigger a red siren in my head. “What?” he’d ask. No answer, only an escalating whale and incessant finger pointing. I must incontestably have been a tiny terror, for on this subject the rest of my family has a catalogue of accounts, among them which involves a nanny that quit on me, the first child ever in her decades of experience. I can vouch for one. It’s about a beast. Nearly 40 years before “Kung Fu Panda” (2008), I came across a stuffed bear as cute and gargantuan as Po, our martial arts caniform. My father and I were in a Hong Kong mall. We had climbed up a flight of stairs to the next level and there he was. Belly to sink into, front and hind legs cushioned stumps, he occupied the entire display window from floor to ceiling. Mini-bears dangled around him like cub cherubs. He was every little boy’s Buddha. “That’s not for sale,” my father insisted. “That’s decoration.” Me: “WahahaaWaahaahaa…” Although I may not have gotten the object of my mewling, I was enough of a disturbance that to silence me, my parents gave me a teddy bear that was as large as I.

“The good thing is that you don’t quit,” my father would say years later. My doggedness has served me well as a writer. Rejections may wound me, but I never bend. Each no urges me to step up one more rung on the ladder to the top. This had to come from somewhere, my bull’s eye on the point closest to heaven. My grandmother once told me of an altercation she had had with my mother over a piano. She spoke as though the incident had happened a week before, no matter that she was suffering from dementia, her memory shot from an aneurism. “Nagkagera kami ng mommy mo tungkol sa piano na iyan. Nangnakuha niya, hindi niya naman tinugtog. Bwisit na piano!” Grandma Susan’s rant that a war had broken out between her and my mother, and that my mother never played the piano upon getting it, humored me. That she spoke with such fire in closing her outburst by damning the instrument meant she still had life in her. We were perusing my mother’s scrapbooks. Black and white pictures in corner holders filled the pages like black ink on white tiles. I have no recollection of the image that triggered Grandma Susan’s scorn. What I do see is one of my mother in heels and a skirt a richness of fabric, her waist tiny and hair voluminous, as she sits, in a sofa, with a smile that radiates confidence in her beauty and the power it yielded her.

Image courtesy of blogspot.com

The stubbornness persists in the generation after me. “Ang tigas ng ulo mo,” my father once told my nephew. Ryan was the age I had been when I made a scene over the teddy bear. Taking my father’s comment of hard headedness in a literal sense, Ryan knocked his knuckle against his skull. “Talagang matigas, eh.” We laughed at his defense that a cranium is meant to be solid. No joke, however, is the solidity of direction he has shown as an adult to be an artist in his own right, music his medium of creativity. Although Ryan doesn’t read notes, melody flows from his fingertips with a strum of the guitar and a tap of the keyboard. He writes songs, having performed his tunes in pubs and talent shows while at the University of Edinburgh and Emory University in Atlanta. Ryan was earning a degree in business. Music was meant to be a hobby. But when we’re that good, our talent assumes a value that surpasses the treasures in Ali-Baba’s cave. Upon graduating, my nephew declined job offers in finance to enter music school in Los Angeles, where he experienced his episode as a struggling artist – stale pizza on the kitchen counter, weight loss, and peddling demos here and there. Will being what it is, he has found his niche in Asia. His songs are requested listening on radio airwaves.

Kong doesn’t deserve his end. The pocketful of gold that is Anne Darow was offered to him as a fruit to pluck; therefore, pluck he did. Her abduction wasn’t his doing. He is guilty of no crime. Snatched of Anne, Kong fights to reclaim what he believes is rightfully his, all or nothing. We would do the same. If given half a glass of water, we in our optimism are supposed to appreciate the little we can imbibe. I disagree. We’re entitled to a crystal goblet filled to the rim. So we charge onward.

Image courtesy of sevone.com