Image courtesy of bydewey.com

Here’s a familiar story:

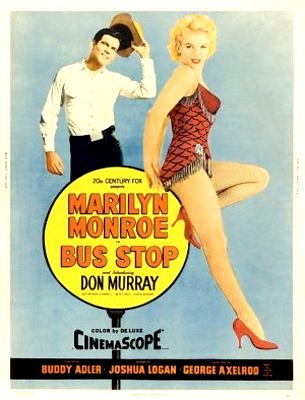

Chérie (Marilyn Monroe) is a saloon singer from the outback with a big dream. Her destination is Hollywood. To earn money so that she could complete her journey, she has taken a detour in Phoenix, Arizona. With the one exception that automobiles now own the streets in lieu of carts and carriages, Phoenix in the 1950s hasn’t developed much since the days of the Wild West. It remains a red neck county where men behave like men. Chérie’s boss bullies her. Her audience ignores her. The siren’s sexiness has run dry with the regulars. But she’s got nothing else to offer. Dressed as a mermaid in black net stockings, she performs “That Old Black Magic” with a voice that sounds more like the whining of a four-legged bitch than the treble of a chanteuse. Enter Bo (Don Murray), a yokel from Montana. He participates in a rodeo, where he rides a galloping bronco and lassoes goats, and because Chérie’s bosom wiggling the previous night at the salon upstages her inability to carry a note, he decides he wants Chérie for a wife, so he lassoes her, too, as he spots her at a bus terminal attempting to run away from him. That’s not how to catch a lady, Chérie tells him; ask with respect. Bo does, and Chérie gets what she has absolutely wanted all along – love and respect.

It’s no coincidence that Marilyn Monroe is Chérie. Although “Bus Stop” (1956) could be any girl’s story, it is specifically that of its star. How many articles have been written about Marilyn Monroe infuriated with studio heads over their disrespect of her? How many about her emotional frailty? About her? Too many. Whenever we read about Monroe, the word “vulnerable” is certain to appear. To be called such isn’t flattering in this age of feminism. No matter. When it comes to our movie goddesses of the studio system, politics fall to the wayside. Vulnerability is the quality that makes the most memorable of them – from Louise Brooks to Deborah Kerr – reach out to us from across the generations. “Hold me. I’m lonely just like you,” they declare with pleading eyes and trembling lips for the two hours that they are resurrected on the screen. We can’t resist. Nobody has ever said no to the pull of beauty. What makes Monroe’s irresistibility perdurable is that she wasn’t altogether acting. We all know her life story. What a mess.

Image courtesy of roxie,com

I’ve seen many Marilyn Monroe films, but “Bus Stop” is my favorite, and it seems to be those of other Monroe viewers, as well. “She just shines in it,” I overheard a girl say in art class when I was still in college at Tufts University. She was conversing with another girl, and though both stated that they weren’t fond of the actress, in this movie, they saw she possessed something. In a film and society course I was enrolled in that same semester, the instructor honed in on the scene in “Bus Stop” where Chérie expresses her ideal mate to a fellow female passenger: “l want a guy l can look up to and admire, but l don’t want him to browbeat me. l want a guy who’ll be sweet with me, but l don’t want him to baby me either. l just gotta feel it. Whoever l marry has some real regard for me aside from all that loving stuff.” The instructor’s lecture was on the pertinence of a role in establishing the image of a star. “Bus Stop,” he said, is pure Marilyn – the loneliness, the idealism, the desperation to be viewed as something deeper than an object.

Image courtesy of blogspot.com

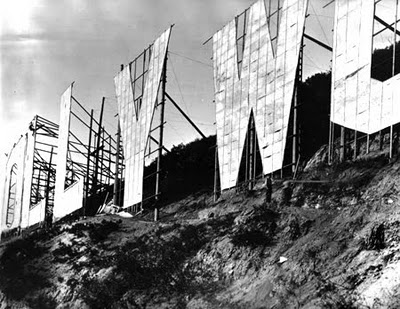

Drag queens glee in playing Marilyn Monroe. They don a platinum wig, pucker red lips, and half close their eyes in bedroom sultriness. They wear a pink gown reminiscent of Monroe’s rendition of “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” in “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” (1953) or a white dress a replica of the one she made famous in that moment in “The Seven Year Itch” (1955), where air that emits from a passing train beneath a subway grate sends its skirt billowing above the knees. They vamp. They lip sync. They ham up the gyration of the derriere and tilt of the head. I do not find their parodies entertaining. While it can be a salute to an actress to be so iconic that she is a favorite of female impersonators, when done to an excess, the parodies detract from her value. It would be impossible for camp to capture the profoundness of the Marilyn Monroe who said this: “I used to think as I looked out on the Hollywood night, There must be thousands of girls sitting alone like me dreaming of being a movie star. But I’m not going to worry about them. I’m dreaming the hardest.” (https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/marilyn_monroe_499735)

I first came across the quote 25 years ago while browsing a coffee table book on Monroe. The anthem of every aspiring artist, it has stuck with me ever since. I know the kind of night she refers to. I would have them when strolling across the Tufts campus on a weekend, everyone except me on one’s way to this dorm party or that, and on the steps of the Sacré Coeur when I lived in Paris, with the cathedral domes in front of me shaped like gargantuan white turbans radiant in the evening sky. I miss those nights. Nothing about the future is impossible in our teens and twenties. My name on a book binding and my profile on a book jacket were a certainty. Not that my confidence has abated; it has merely been put to the test with age. Someone who had worked in a literary agency told me that even representation by an agent doesn’t guarantee publication; only 5% get a book out. My response was that I don’t give a damn about the 95% that don’t make it. Otherwise, why even bother with this? Until I am a part of this select group, I gaze in the late hours at the wide expanse of stars and wisps of lavender clouds, and I hope.

Image courtesy of ebayimg.com

Chérie in “Bus Stop” may not have reached Hollywood, though that’s because she finds something better – a man who sees her as an angel despite her admission to having been around the block. That’s Monroe right there, a sex symbol in search of a guy who could love her as Norman Jean, only the actress’s dreams were too grand for her to dismiss, which is why she speaks to our ambitious nature. Monroe got what she wanted. As evidenced by what happened to her, superstardom isn’t everything glossy magazines and tabloids hype it up to be. Still, we want her dreams for ourselves, regardless of the danger entailed or the lives imperiled. Bad luck aside, the end result is undeniable: Marilyn Monroe is immortal.