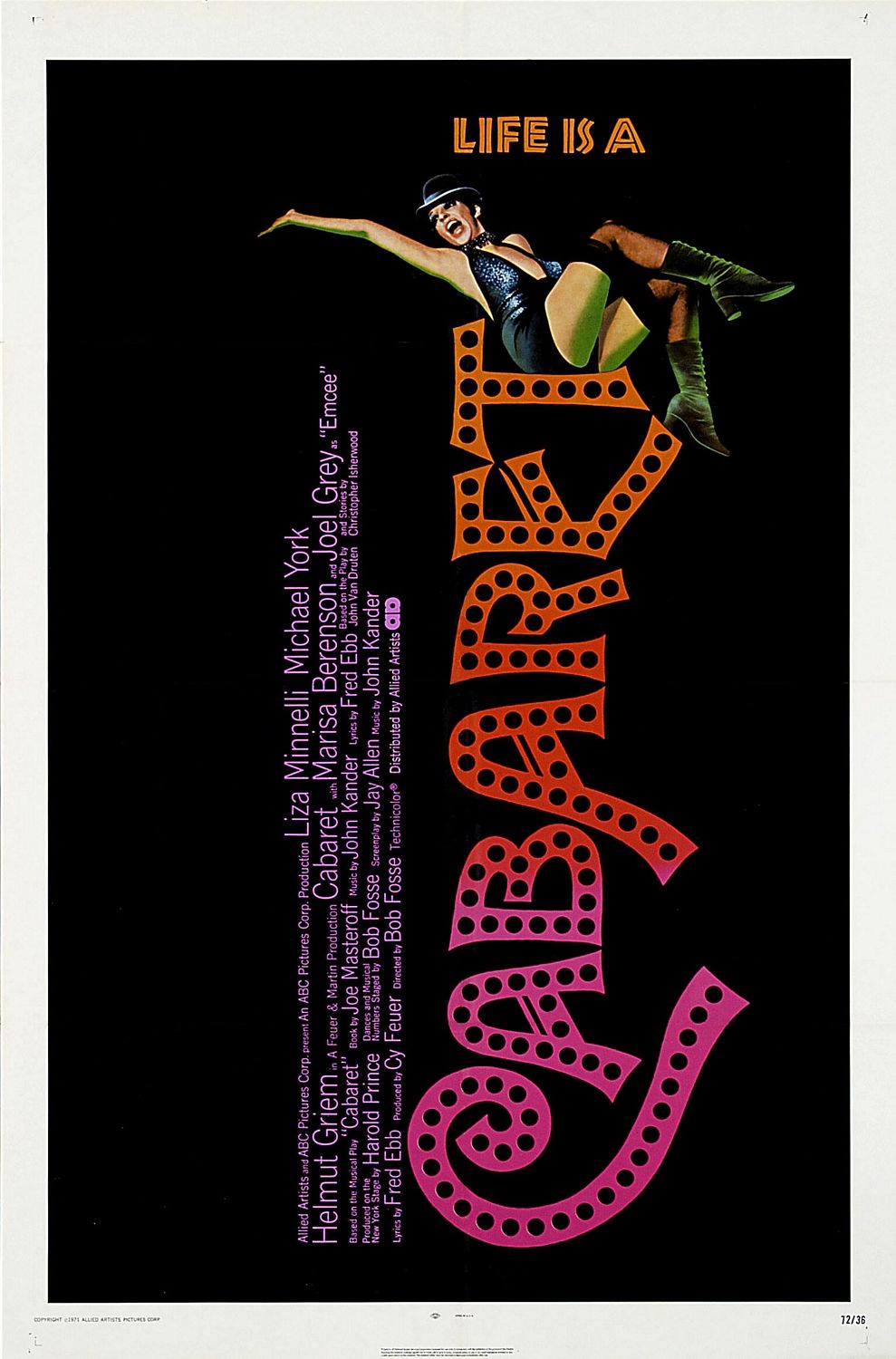

Image courtesy of pinimg.com

A writing instructor gave me the following advice: when creating a story, adapt the role of a filmmaker. No literary wisdom has impacted me more. To make a movie requires a crew, costly gadgets from the sound system to the camera, and financial backing. To pen a novel calls for one item alone – a laptop. Through the letters I type, I am the director, actor, screenwriter, light technician, costume designer, and cinematographer. Moonlight through a window crack enhances mood. Dialogue incarnates characters. The description of a town replicates the material world. As a result, images appear on the page, producing a motion picture projected through a camera in the mind. You, my readers, sing and fly, eat and make love, and in the symbiosis between language and visuals, we learn together that all art forms are connected.

Poetry is dance. Dance is music. Music is poetry. Oscar Hijuelos, in “Mambo Kings Sing Songs of Love,” infuses prose with melody, while in “The Lover,” Marguerite Duras guides us on a ballet up the Mekong River. For Thomas Hardy, the title heroine to “Tess of the D’Urbervilles” is the central figure in a tragedy of operatic proportions. (http://www.rafsy.com/actors-models-directors/nastassja-kinski-the-eternal-tess) All of these books were made into cinema, some more memorable than others, though none quite like that based upon “The Berlin Stories,” the Christopher Isherwood classic that narrates the end of a fabled existence among a cast of bohemians during Germany’s bleakest hour.

Image courtesy of cloudfront.net

I discovered “Cabaret” (1972) when I was in high school in Manila. My finding may have been by chance, but it was destined. English courses had awakened in me a curiosity for the recesses of a scribe’s mind. Since too much is out there for one person to read, I resorted to the medium that could instantly gratify my hunger for the imaginary: film. Thanks to betamax, I could view in their entirety, at my convenience, some of the greatest stories ever told, their titles lined on floor to ceiling shelves for me to select as tickets to a lottery. Musicals guaranteed a jackpot. They were manufactured for a singular purpose – to portray life as a lyrical marvel, our destitutions in equal measure to our gains. “Cabaret” struck a chime in me that has reverberated through the years because the Bob Fosse choreography and John Kander/Fred Ebb libretto are performed where they would have been in reality – a nightclub – and given the prurience of the stage acts and the slovenliness of the patrons, a gloominess taints the love affair between Sally Bowles (Liza Minnelli) and Brian Roberts (Michael York) that impelled me to root for them.

Maybe this time, I’ll be lucky. Maybe this time, he’ll stay. Maybe this time, for the first time, love won’t hurry away. He will hold me fast. I’ll be home at last, not a loser anymore like the last time and the time before.

Such is the hope in Sally as she sings of a beginning with Brian. They meet as neighbors in the same building. She is burlesque entertainment. He is quill and scroll. She is street smart. He is Cambridge educated. The one factor that holds the two together is that they are both outsiders caught in a party where the curtain is about to descend. That it’s the wrong time for a relationship is also the reason that the time is right. Brian and Sally would never have connected under peaceful circumstances. They might never even have met. He is in Berlin to complete his doctorate, subsisting as an English tutor, while she has made the capital her home because Europe is kismet to an American libertine. The mating of the cerebral with the libidinous results in a romance that, amid the looming threat of the Third Reich, turns desperate: love today, for tomorrow could be too late.

Image courtesy of i.dailymail.co.uk

As foreign to my culture as “Cabaret” is, the movie possesses an immediacy that bespoke my desire to be an artist. I was already aware at 17 that convention was never to be my fate. I wished for Sally’s passion. When she takes to the spotlight, she belts out her soul. She fastens her stance with arms open and legs apart, as indestructible as a marble statue. Her boldness wallops every Joe and his whore at the Kit Kat Club. I saw my future. Go west, I thought. In conquering far-off regions as Sally does, l would assume center spot on the world stage, in works of my creation.

College in Boston brought me for my junior year to Paris, where during a course on the Weimar Republic, I spent a week in Berlin. Christopher Isherwood was part of the reading syllabus. Though I’m more a novel person, I was smitten by his tales of common folks in a boarding tenement, with small dreams and big disappointments. Berlin made a gorgeous backdrop. When I was there, the wall still existed. Buildings modeled after corporate headquarters in America’s financial hubs towered across the West. Brand names such as Sony and Maxell were plastered on their facades, floors above popsicle-bright awnings, and a throng milled about the avenues. In the East, people walked in uniformity; military officers patrolled the streets; edifices were colossal and industrial gray. Since the season was spring, the days were sunny and trees were in full bloom so that citizens from both sectors had reason to smile. And amid the modernity, Grecian columns and statues of winged horses affixed on palatial structures harked back to Germany’s imperial glory. Never mind that five decades separated me from the Berlin in “Cabaret.” I saw it everywhere, what Isherwood must have called inspiration.

Before “The Berlin Stories” was transcribed onto celluloid, it was the basis for a theater piece. “I Am a Camera” is Isherwood’s testimony of the artist’s obligation to humanity. We are the record keepers of our species, the eyes to history. Our notes and pirouettes, our sentences and images, are first-hand accounts of a moment without which future generations would never be. Some moments are honorable. Some are deplorable. All magnify life’s preciousness.

Before “The Berlin Stories” was transcribed onto celluloid, it was the basis for a theater piece. “I Am a Camera” is Isherwood’s testimony of the artist’s obligation to humanity. We are the record keepers of our species, the eyes to history. Our notes and pirouettes, our sentences and images, are first-hand accounts of a moment without which future generations would never be. Some moments are honorable. Some are deplorable. All magnify life’s preciousness.

Put down the knitting, the book, and the broom. It’s time for a holiday. Life is a cabaret, old chum, so come to the cabaret. Come taste the wine. Come hear the band. Come blow your horn. Start celebrating. Right this way. Your table’s waiting.

These words sum up why we are on this earth – to have a ball. My foray into adulthood wasn’t easy. Love eluded me, and I couldn’t reconcile my body with the vision of the man I ached to be. Even so, I took my table, blew my horn, and spared no wine. Of this, I’ve got proof. In a photo of me in East Berlin, I am at the Altes Museum, posing with the statue of a nude Amazonian female head and shoulders taller than I. I am wearing a pair of jeans I had bought at a market in Paris. I had intended to bring the jeans on a school trip to the Soviet Union as a bartering tool since it was common for tourists to meet locals in their hotel lobbies with whom we could exchange a Western product for a Soviet item. Instead, I kept the jeans because I liked the fit. Now I laugh at how wrong the jeans were, loose and lengthy. And yet, the photograph captures something beautiful in me that I never saw in the mirror.

I am upright. I am self-assured. I am beaming. The future lies before me a horizon of white clouds reflected on windows and a door that opens to heaven, a home built on stories I have yet to write.

Image courtesy of dailyprayer.us