We met at the Hotel Nikko gym, where Tristan Ledan worked as a weight training instructor. With his head shaved and a dimpled smile, he had a baby face on a pugilist’s body. Tristan’s uniform was a collared red tee shirt that marked him like a flame. I could see him from the corner of my eyes no matter where he was – at the window, in front of a white wall, reflected in a mirror. Against the view of the Eiffel Tower, amid the black and white nautilus machines, Tristan was a blot of red that seemed to appear from nowhere. He would be absent upon my arrival. Then in an instant, he’d be there. Since he was genial to everybody, I never gave his smiles a second thought.

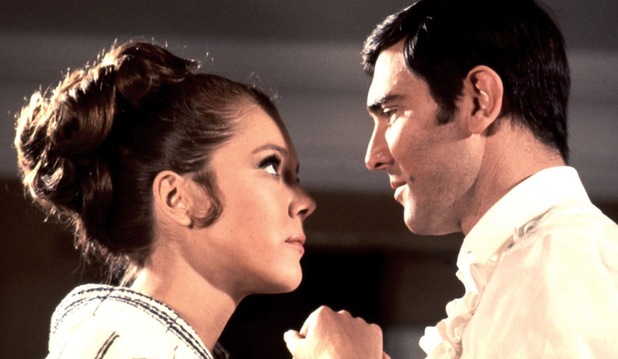

Image courtesy of allpostersimages.com

Things changed the second semester. I was doing bench presses in front a mirrored wall, while he was beside me, guiding a man through push-ups. What a sight the two of them made. Tristan, in a squat position, flaunted muscular thighs bursting through his jogging pants. His client was heavy set and breathing weightily as perspiration dripped from his hair. Through the mirror, I was admiring the client his diligence. So languorous was Tristan in counting the push-ups that his client’s fatigue didn’t seem to faze him. “Dix… Onze… Douze…” – Tristan sounded as though he was singing a lullaby. Yet the client would not stop until he was told to stop. Even when his arms were about to buckle, even when his back was giving way, the client wanted more – more push-ups, more treadmill, more of anything that Tristan would instruct of him. When I had arrived half an hour earlier, the two were already in the midst of heir session, and it didn’t seem to be ending soon. I understood the man’s zeal. He had quite an image to emulate in Tristan.

I sat on the bench press, transfixed. In my mind I was cheering the client on. He was emanating so much energy that he fogged the mirror. Now he was clapping his hands in between each push-up. I couldn’t even do that. My reflection in the mirror gave evidence that I had come a long way since high school, since my arrival in Paris seven months earlier even. My acne had cleared, and though it left its trace, I was only glad that the pock marks were not of the moon crater variety. (Richard Burton had blemished skin and look at who he got to marry twice.)

Still, I had just turned 21. The me I was meant to be was a work in progress far from complete. I figured that if this man whose stomach bounced on the floor with each push-up could strive for perfection, then so could I. I had heard Tom Cruise isn’t tall, that he is my 5’7”, yet how tall and marvelous he looked in “Top Gun.” I may never look like Tom Cruise nor may I be as buffed as Tristan, but I decided right then that I could at least work with what I have as much as this man beside me was working his darned hardest.

All these good thoughts of a future me must have washed my face aglow because at that instant, in the mirror, Tristan darted his eyes at me and he smiled.

“Après,” he mouthed.

Huh? Afterwards? I pointed a finger at my chest and I mouthed, “Moi?”

Tristan nodded.

I shrugged my shoulders. “Pourquoi?”

Tristan smiled roguishly.

I wanted answers: What time was après? Should I dare believe this to be a come on? Was this really happening?

Instead, I moved away from Tristan in order to avoid appearing eager. I dilly dallied with this dumbbell and that Nautilus machine. On a mat, I considered trying the hand clapping push-ups, then decided against it lest I prove myself a klutz. My concentration shot, I could hardly work out. Tristan’s session with his client could not end soon enough. I kept glancing at Tristan in the mirror, from the side of my eyes, across the weight room. He’d respond with a quick look and a nod. No doubt about it, the guy was flirting.

The client’s stepping into the locker room indicated that après had arrived. I followed him to get my things. Tristan went to the front desk across from the locker room, where he stepped into an employee room behind. He didn’t make eye contact with me, so I worried that he might have lost interest, until a few minutes later I saw him outside by the elevator, gym bag slung over his shoulder, downing protein juice and waiting.

Since I didn’t want to make the same mistake with Tristan that I had with Rick, I assessed the signs: for the whole of my first semester, Tristan had said nothing more to me than “bon jour,” “comment ca va?” and “a tout a l’heure”; I had responded with the likewise salutations of good morning and see you later as well as a “bien, merci” to his question regarding my well-being; he had smiled at me from time to time and I had smiled back; we were polite. Did he really mouth “afterwards” to me oh so seductively in French just a moment earlier? What was I getting myself into? And yet, Tristan was standing in front of me, an arm’s length away. He wasn’t smiling. He was grinning. Then he blinked… coyly. If this turned out to be another misreading on my part, then so be it. No pain, no gain.

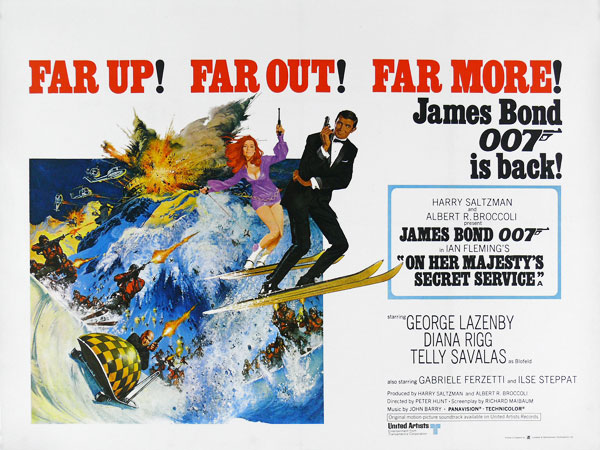

Image courtesy of wordpress.com

Tristan asked me something. I gave him a blank look. Even after half a year in France, my French was iffy.

“Parles lentement, s’il vous plais.” I told him to speak slowly, please.

Meanwhile, the French that incessantly played in my head as a broken record was the line from that silly disco song, “Lady Marmalade” – “Voulez vous coucher avec moi ce soir” – if only because the line is downright awkward. Vous is a formal term for the second person, used on an individual of age or rank or on a stranger. Of course, Tristan was a stranger, but we were going to have sex. (I hoped). Addressing him by vous would have been equivalent to calling him Mr. President. What exactly do the French say when they want to fuck?

“Nous pouvons aller chez moi,” Tristan said. “Ehh… my place.”

“Yes,” I said. “I mean oui.”

That was all it took. After fumbling over French and English and umms and ahhs, all a man had to do was to invite the person over to his place. This wasn’t as blatant and gauche as “would you… sir, Mr. President… like to go to bed with me tonight?” but it expressed everything. Tristan and I had nothing more to say to each other.

The metro ride to Tristan’s place was a series of smiles peppered with questions of “quoi?” and “what?” over a comment on the gym, my schooling, and weekend activities. We were seated on a double passenger chair. Amid people who milled around us at each stop and the rolling of the wheels on the tracks, I wanted to ask why me. I wasn’t muscular. I wasn’t flirtatious. I had given no sign of interest nor of availability. Then again, why ruin an impulsive moment with self-analysis?

Tristan placed an arm around my shoulders, brought me closer to him. His down jacket was soft. His touch was hot. I traced a pink mark on the left side of his neck.

“Marque de naissance,” he said.

I showed him my own birth mark. It was on the left side of my neck, too.

“Nous sommes jumeaux.”

I didn’t understand him, but I said oui. That was all everything we were doing from this point on required of me anyway – a yes.

Trees against a blue sky and glass towers juxtaposed with Victorian buildings passed in the window beside Tristan like shifting stage sets. Then we were underground again. As the metro stopped, Tristan said, “Nous sommes ici… Here, the two of us.”

The building Tristan lived in was a block away from the metro. It was one of those old Parisian dwellings with a cage elevator and a winding stair well, water stains on white walls and a frayed carpet. His studio was a mini-museum that displayed prints of Chagall and Van Gogh alongside Robert Doisneau and Brassai photographs. 1950s street shots of Parisian lovers locked in a kiss, the Arch of Triumph, and the Seine River mystic with street lights sparkling through mist sent me in a time warp. Reality blended with the dream of a starry night rendered in turbulent brush strokes and of amorphous figures of bulls and horses and people floating in space brilliantly colored. Tristan wasn’t just a beautiful looking man. He had a beautiful eye.

How exactly does he see me? “Tu est…” I simulated painterly brush strokes with my hands.

“Peintre? Non.”

Image courtesy of gstatic.com

So what did he do if he wasn’t a painter? Photo books of male physiques, tabloid magazines, and a pair of Sylvia Plath books filled a set of standing shelves. Beside that, Charlie Brown and Linus piggy banks decorated his desk on which lay an open journal. Frenetic penmanship left no space on the page. Elongated letters slanted right as though Tristan had been chasing after his thoughts, hurrying to record them before they vanished.

“J’ecris,” Tristan said.

“T’ecris quoi?”

Rather than answering, Tristan kissed me. Or maybe the kiss was his answer. Maybe love and sex were what Tristan wrote about.

I closed my eyes. Suddenly, I forgot everything in the studio I had seen and everything I had been thinking. Tristan’s tongue alone reminded me that I was alive. Until that moment, I had understood a French kiss to involve placing the tongue in another person’s mouth and that was it. Tristan was tongue kissing my chin, my cheeks, my ears, my nose. This was more than a mere avalanche of lascivious kisses. The man was making love to my face. He was grinding his tongue so deep into me, sucking my face so hard, that I could hardly catch my breath. I was losing my footing. The two of us were standing in between the desk and the foot of the bed. He held me up and motioned me closer to the bed.

“Meow,” I heard.

“Mrrrrgrrrmm,” I grumbled. I couldn’t release my mouth from his. I struggled to talk. When finally our faces parted, I said, “Un chat?”

From underneath the bed, a pair of blue eyes in a furry head the orange of a pimp suit gazed up at me. A feline Rick Vogt.

“Shit, I’m allergic to cats,” I said.

I don’t think Tristan understood. Even if he had, I doubt it would have mattered because it didn’t matter to me. Not at this point. I was on the verge of a divine discovery. We fell on the bed. I had never known flesh so soft that I could sink into it nor muscles so solid that they promised reliability.

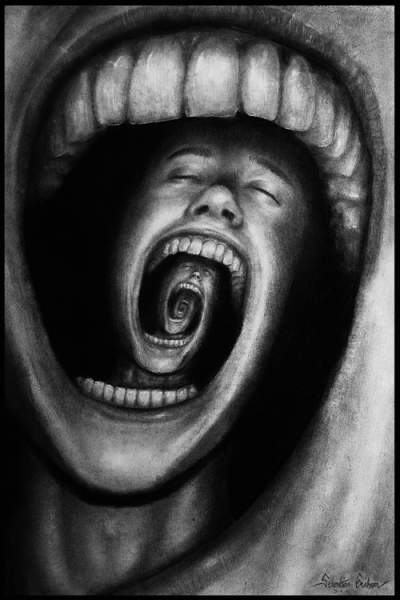

The radiator rattled. Legs raised in the air. A car screeched outside. Heads thrashed against pillows.

We intertwined our limbs, desperately so, as if all the love in the world were to end upon midnight. Then Tristan stopped kissing me. He raised his head, gazed at the ceiling. He could have been watching a miracle rain down. Though our mouths were agape, we uttered no words. Our hefty breathing escalated into a cry. I didn’t even realize we were making such a raucous until Tristan clamped his hand on my mouth and diminished his own sounds into a grunt. But the humping of our hips didn’t stop. We picked up momentum. And then…

Our bodies stiffened. The energy pent up inside of us was too much to fight against. Life for an hour had been heat, speed, and friction. It was ending on a soft note of a moan and ebbing twitches of the groin.

Tristan fell by my side. He sighed and he laughed a laugh more an expression of delight than of humor. Exhausted as we were, our heart beats were racing.

“Water?” Tristan acted out drinking from a glass.

“Non, merci.”

During our bed pounding, the cat had moved to the desk chair. It was staring at me with lightning eyes. That was when I started to feel it – an itch on the arm and an itch on the neck. I sneezed.

“Ca va bien?” asked Tristan.

Oh, jolie cat, I thought. You are not making me feel well. “Oui,” I said even so.

I didn’t stay the night. I didn’t even stay till midnight. Tristan slipped on a pair of boxers and sat on the edge of the bed. That was hardly an invitation, so I put on my clothes.

The first shimmers of the evening lit the window through the Venetian blinds. Van Gogh in a self-portrait above the bed looked sad.

“Merci,” I said. “Merci beaucoup.”

“Merci aussi.”

Tristan didn’t offer his phone number. I didn’t know to ask. He hugged me, but he didn’t kiss. He hugged me for the last time ever.

Image courtesy of imagecache6.allposters.com

At the gym from that night on, Tristan was distant. I would walk up to him at the front desk or in the weight area and say hello, then stand tongue tied. No amount of schooling teaches a boy what to say and how to act in this situation. How I must have seemed to Tristan a begging urchin, far from the lovable lovelorn innocent that Audrey Hepburn’s Sabrina is. He hardly said much himself other than his usual salutations because he was always in a rush. He was hurrying to tend to a client or he was speed eating in the employee room. He was fast talking with his colleagues or he was sprinting out the door, to the elevator, and out of my sight. He’d wink at me sometimes, nothing more – never a moment to chat, never a look between us long enough to acknowledge having connected. Tristan and I may as well had gone out to have a drink rather than have sex. Indeed, that was all I had been – a fresh bottle of testosterone for him to quench a thirst. But had my nectar not tasted sweet? Had Tristan not said that we were… What was that word?

Jumeaux, Enzo informed me, means twins. In a way, Tristan was right. By taking me to his bed, he had initiated me into a brotherhood of fly by night flings, a fraternity that in its absence of women bypasses the convention of courtship and that sacrifices emotions. As a new member of the family, I needed to adapt to its customs. Within a month, Tristan and I reduced to acknowledging each other with a mere nod and then with nothing at all. Instead of allowing myself to dwell on heartache, I decided to sample the array of male delicacies that Paris provides. Love had to be hiding somewhere amid the play, like a cherry in a cream pie.

Gay men are available for the taking in the Marais district, once the domain of the Parisian aristocracy in the 19th century. Cushioned fold out chairs that match the color of the awnings, rainbow flags that deck doorways, and clothes along with glossy magazines in display windows framed purple, green, or blue give a splash of vibrancy to the cobblestones and palatial buildings murky in their staidness. The Marais has long ceased to be about protocol. The Marais has come to represent non-conformity. The ghosts of the nobility might disapprove, but on my first venture to a gay bar, I imagined the spirits of Honoré de Balzac’s courtesans sweeping the hems of their crinoline gowns against the floor in a waltz danced in rooms where men in Doc Martens and pierced ears today drink and fornicate. I might have hurt from Tristan’s avoidance of me, yet what I had gained from him far outweighed the pain. I was going to have the time of my life. I dressed like the guys I wanted – in baggy jeans, a logo tee, and my hair a crew cut – and what I wanted was a guy after the image of Rick or Tristan. I couldn’t forget Gavino Bellandini either, no matter that he was too darn godlike to be attainable. If a surprise such as Tristan Ledan was possible, then anything could happen.

That was the problem. I expected love to be instant and lust to be mutual. Although not everybody at Quetzal Bar fit my ideal, there were enough who did so that I was convinced that I was what they wanted, too. No. The chattering of men divided into groups reminded me of BAGLY. Only in this case, the groups never disbanded to form one large gathering of friends. Punk rockers stuck with punk rockers. Fashionistas stuck with fashionistas. Skin heads stuck with skin heads. I sat on a stool in front of a mirrored wall and kept company with a glass of soda water. That the end of my straw was producing gurgling sounds didn’t matter. Nobody heard.

Nevertheless, I didn’t lose hope. In my perseverance, subsequent outings to Quetzal didn’t amount to naught. Men would engage me in conversation, and occasionally, I’d meet a person whose handshake felt as though I had found a missing link.

There was the airport customs official who confided in me “J’aime les garcons Asiatiques.” In his flat, under dim red lights, he caressed my body as if it were a bronze sculpture. His hands were not large, but his touch was electrical. He was meaty on the stomach, but he was young and burly. As he waxed poetic on the Asian men who traveled through Charles de Gaulle Airport, his eyes lit up as if he were reciting a mantra.

Image courtesy of deviantart.net

I had a royalist, it’s true. His living quarter was as bare as a prison cell. Only an open drawer over which a shirt sleeve hung attested to a life within those four walls, as did his most prized possession: a scrap book containing postcard-image sketches of chateaus and castles once under the ownership of ancestors who had met their end at the guillotine. I didn’t understand his monologue on the merit of reviving the monarchy. I had never even been aware that royalists existed 200 years after the storming of the Bastille. Yet I had a sense of his frustration; Marcos supporters… or loyalists as they were called… were bent on usurping Corazon Aquino. Politics aside, the man knew how to wear a jock strap.

With the Moroccan medical student, my duplex was the play space. I didn’t dare bring him to my bed; a girly quilt would have killed the mood. We lay instead on the sofa in the living room. The Renaissance hunting scenes on cushions that depicted guns and horses on a mad chase after foxes were more conducive to our intentions. Predator or prey, he and I were each a bit of both, clawing at one another and biting. For extra income, the guy worked as a nude art model. “Regardes moi,” he’d say in the midst of making out. That was his kink – being watched as he struck sexy poses on the shag carpet.

Despite my numerous instances of two lives shared, my kisses with each man were more a hunger of the groin rather than an expression of the heart. Even so, the world became a smaller place. If men whose lives were never meant to converge could find a common bond in me, then love was possible with anybody, anywhere.

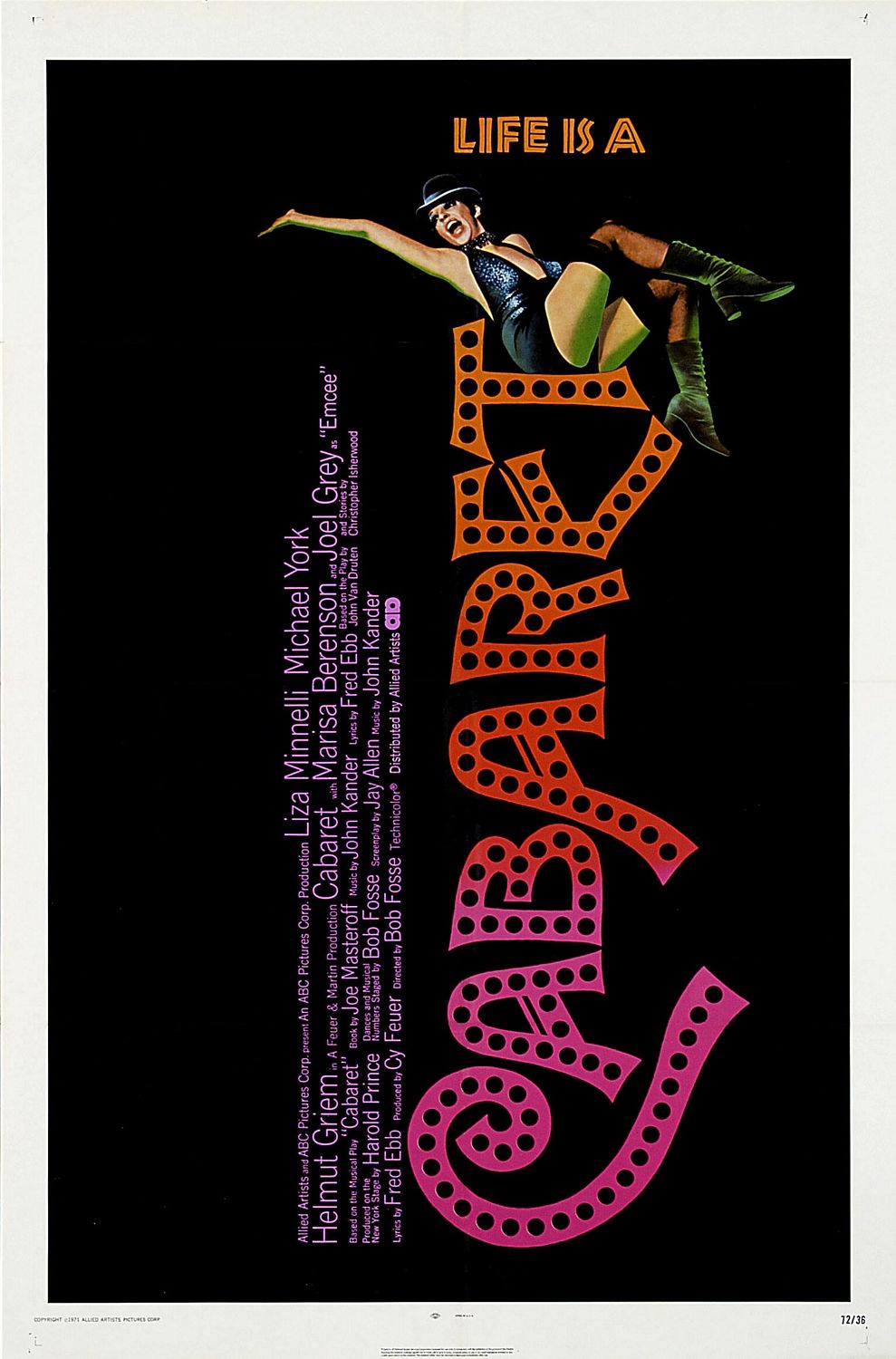

Gay establishments outside of my comfort zone of the Marais started calling to me. They were nearly as plentiful as movie theaters: Dance Club at Les Halles, where from railings on the second and third levels, I could watch potential mates on the dance floor; a porn video arcade at Pigalle, a neighborhood once home to Toulouse Lautrec; and Le Trap at St. Germain des Pres.

Le Trap. The bar was an oddity to stumble upon in a neighborhood of swanky boutiques and fine dining. While Quetzal radiated light and space, Le Trap was the nadir of darkness and sleaze. Its clientele was of the hyper-masculine type. Leather chaps and chains, tee shirts two sizes too small and jeans tight on the butt all seemed to have been lifted from the Al Pacino film “Cruising.” Just as the film depicts, the men were there for one reason alone, and it wasn’t love. The bar area was so small that body contact was inevitable. A spiral staircase led to a floor that was immersed in blackness. Blind as I was to the activities within, the sounds surging forth supplied the visuals for my imagination.

Curiosity had taken me to Le Trap. The place wasn’t to my liking. It was enticing and mysterious, no doubt, but I had not yet acquired the footing to stand alongside these giants. I stayed even then. It was May, the end of my year in Paris. To fulfill my mission for adventure, I needed to claim Le Trap as one more horizon explored.

No, Le Trap was not about love. I had searched for it in the cream pie that was Quetzal. I certainly had no expectations of finding it in this mud pit. For my one and only night there, I remained on the stairs, unavailable to the men at the bar below and the men in the backroom above. The sting of cigarette smoke in my nose, the sugary spirituous smell of liquor, and the heat from bodies joining were all I needed to be engaged in the reality of the moment. This would be enough of a memory.

Goodbye, Paris, I thought.

Footsteps clanked on the metal steps. Moans and groans thundered from the backroom. Guys kissed and groped in the bar.

I preoccupied myself with the mechanics of moving back to Tufts. Tomorrow I would buy boxes for my books. In a couple of weeks, I would disconnect my phone. I would be back in Boston before I knew it. Davilo had sent me a telegram asking to house with him and Owen. That was something to look forward to.

And right then, right beside me, the cherry in the cream pie materialized in the body of a tall, dark, and handsome Swede who spoke fluent English.

Image courtesy of cloudfront.net

/033000004026-37%22x13%22-Masters-Panoramic-Art-Print-The-Rest-By-Pablo-Picasso.jpg)