This is one career misfire my mother cannot put to pasture: I could have been the next Robert Doisneau or Milton Greene. In the summer of 1987, I roved Boston for a job as an apprentice to a photographer, a portfolio in tow of pictures I had taken in the Philippines following the People Power Revolution a year earlier that had ousted Ferdinand Marcos from his 20-year dictatorship. The pros welcomed my knock on their door (they must have been impressed by this 20-year-old’s moxie), and they provided me advice and compliments (“you have a good eye”).

This is one career misfire my mother cannot put to pasture: I could have been the next Robert Doisneau or Milton Greene. In the summer of 1987, I roved Boston for a job as an apprentice to a photographer, a portfolio in tow of pictures I had taken in the Philippines following the People Power Revolution a year earlier that had ousted Ferdinand Marcos from his 20-year dictatorship. The pros welcomed my knock on their door (they must have been impressed by this 20-year-old’s moxie), and they provided me advice and compliments (“you have a good eye”).

The best response came from The Boston Globe. I dropped off my portfolio with the guard at the front desk, instructing him to deliver it to the photo department. Three days later, I got a call from the newspaper. “We got your portfolio and we’d like to talk to you,” the woman at the other end of the line said, to which I responded that I only wanted to work on certain days and at my chosen hours. “I’m sorry,” she said. “We can’t help you.” The truth was that I was so lazy that I didn’t want to work at any hours on any days; thus, I dismissed the Globe’s rebuff of me as minor. I can try next year, I thought. The second time around brought no such luck with either the Globe or anywhere else. “And you thought it would be easy,” my sister said. Some life lessons are a hard learn, and this is one of them. I blew a once in a lifetime chance; not every kid gets an employment summon from a major newspaper. “You should have…” my mother says to this day.

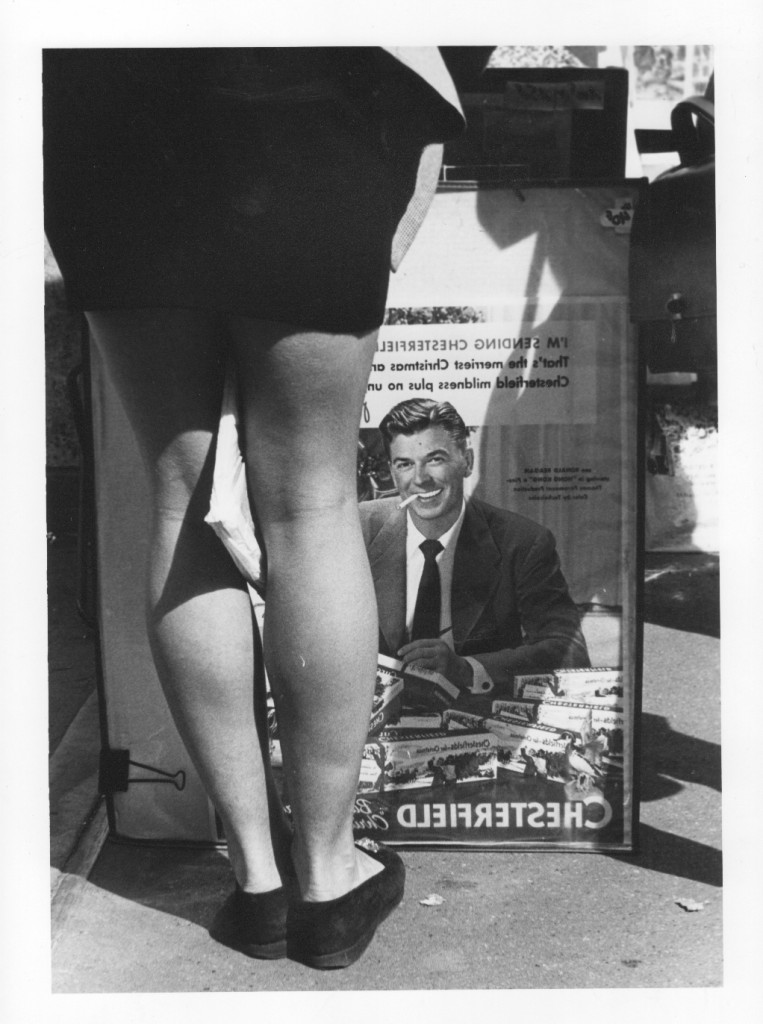

I do wonder how my future would have been different if I had. I would have been a storyteller, albeit with images rather than with words. The narrative of a picture is what got me interested in the medium in the first place. I’ve always been a visual person. Before writing, I drew, and it had been for this art form that I was rewarded in high school. People were my subjects, specifically women from the pages of fashion magazines. I was attracted to the quixotism a model embodies. A heroine to a story played out in clothes and make-up, she is not unlike an actress, only in her case, the viewer supplies the dialogue and the plot; I could shape her in accordance to my mood and my whim. Photography was a rational next step. As the person behind the camera, a shutterbug possesses power in the role of a director. With a single shot, he or she could capture an emotion. A skirt is never more provocative, a handbag never more romantic, than when captured amid a misty sunset, smoke in the background spiraling upward from a cottage chimney, on a woman who channels Veronica Lake.

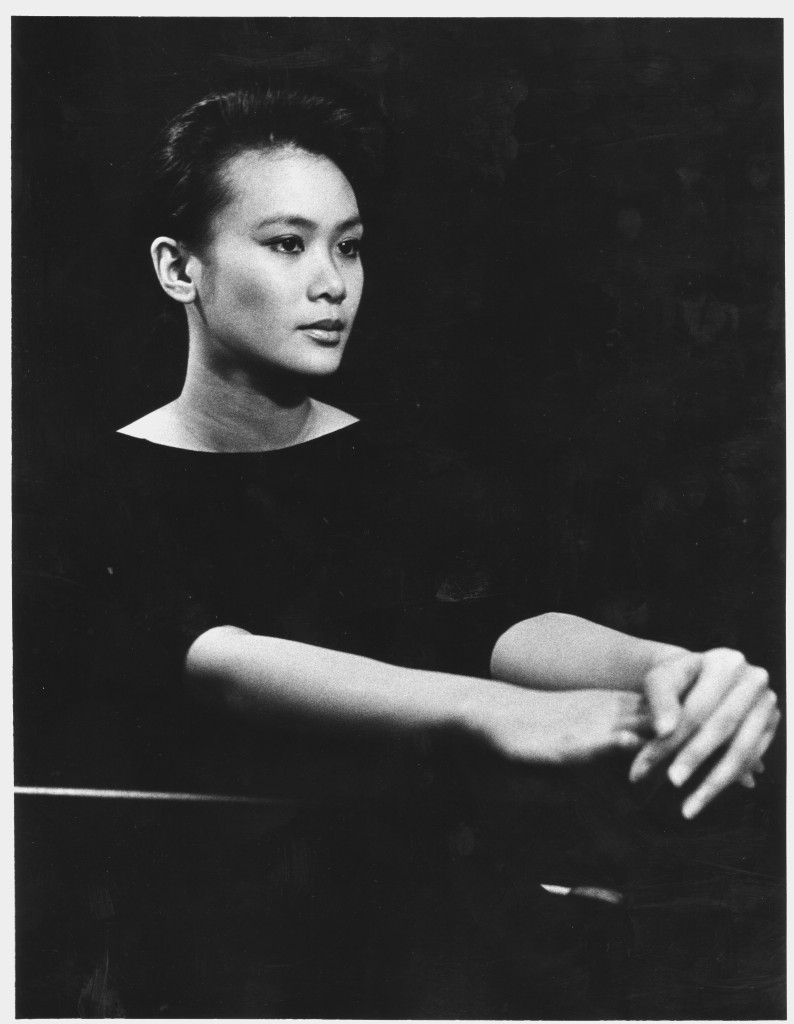

Photography was my method of creating my own Hollywood classic. I purchased my first 35mm camera for an introductory course during my freshman year at TuftsmUniversity. My sister herself had just entered the architecture program at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, which was a 20-minute bus ride away from me, and on a few occasions, I would use her as a model. For direction, I’d mention studio portraits of Greta Garbo et al. Since my sister and I along with our mother used to watch old movies together, my sister didn’t need clarification when I’d say, “Frame your face with your hands like Garbo… Give me a profile like Grace Kelly on the cover of Life… Like Rita Hayworth… Like Vivien Leigh…” She was aware of each pose I was referencing. So natural was she that after a click, she’d sway her arms into another star pose, her expression a composite of daring and aloof.

Photography was my method of creating my own Hollywood classic. I purchased my first 35mm camera for an introductory course during my freshman year at TuftsmUniversity. My sister herself had just entered the architecture program at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, which was a 20-minute bus ride away from me, and on a few occasions, I would use her as a model. For direction, I’d mention studio portraits of Greta Garbo et al. Since my sister and I along with our mother used to watch old movies together, my sister didn’t need clarification when I’d say, “Frame your face with your hands like Garbo… Give me a profile like Grace Kelly on the cover of Life… Like Rita Hayworth… Like Vivien Leigh…” She was aware of each pose I was referencing. So natural was she that after a click, she’d sway her arms into another star pose, her expression a composite of daring and aloof.

Our favorite actress to emulate was Audrey Hepburn. (http://www.rafsy.com/films-1960s-1990s/breakfast-at-tiffanys-sunshine-through-rain-clouds/) Although we had both watched “My Fair Lady” (1964) as kids, it was our viewing of “Sabrina” (1954) the year my sister returned to Manila after graduation from Columbia University in New York that made us fans. The actress’s ramp model physique is relatable to every generation of fashion aficionados, and this my sister and I certainly are. The peacock dress, the pixie cut, the opera gloves… “Sabrina” is an instruction on style. “I keep telling you, it will be too much,” my sister insisted upon my insistence during one session that she darken her brows in Audrey manner. I was in no position to argue, she being the expert on eye pencils and lipstick, and I was only too thankful that she was willing to be my guinea pig. Amateurs, we both had to make do with whatever equipment was available: a black dress, a black TV stand, table lamps, and a backdrop of a gray blanket draped on closet doors. In the darkroom, classmates hovered around me, amazed at the girl whose image was materializing on the print sheet. “Jesus,” my sister said as I presented her her portraits. “Do I really look like that?”

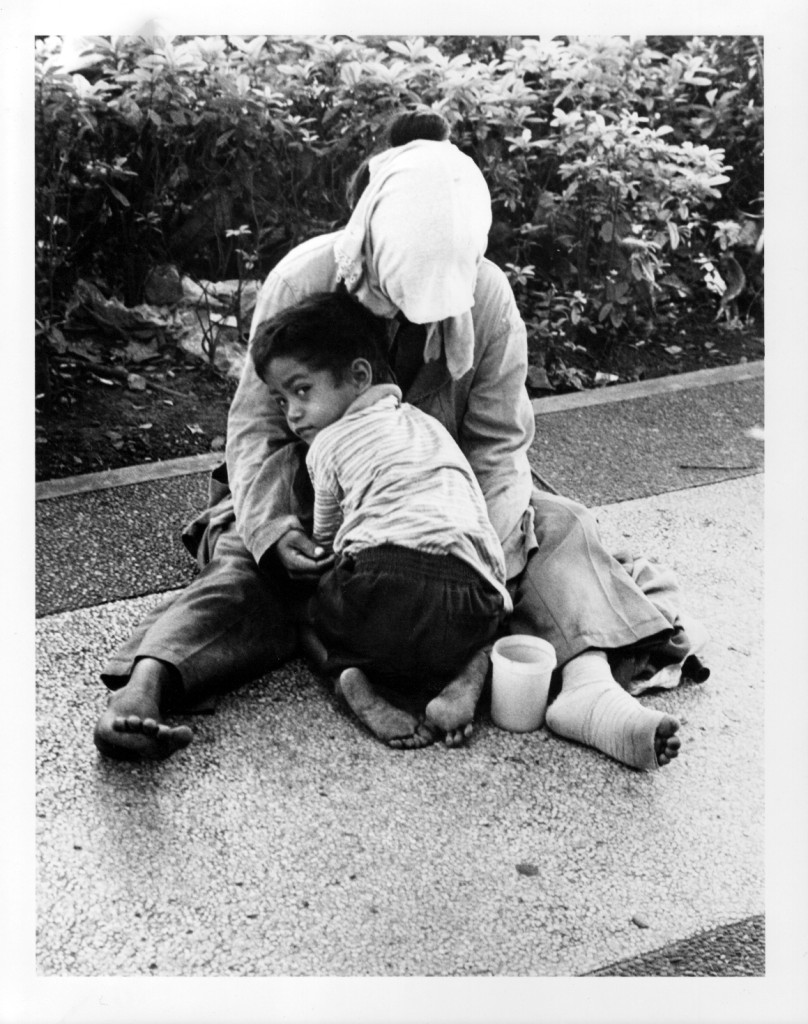

Along with movie stars and models, I was keen on the regular folks on the streets, the truth of their stories in contrast to the escapism of a beautiful woman. I eschewed staged shots. They had to be candid, caught in the midst of an individual engaged in one’s routine of living. If a subject were smiling into my lens, then it was a pose caught by happenstance. Of this hold humanity has on me, I have dedicated a section to it in a novel I would write some 25 years later that I’ve entitled “My Wonder Years in Hollywood”:

Along with movie stars and models, I was keen on the regular folks on the streets, the truth of their stories in contrast to the escapism of a beautiful woman. I eschewed staged shots. They had to be candid, caught in the midst of an individual engaged in one’s routine of living. If a subject were smiling into my lens, then it was a pose caught by happenstance. Of this hold humanity has on me, I have dedicated a section to it in a novel I would write some 25 years later that I’ve entitled “My Wonder Years in Hollywood”:

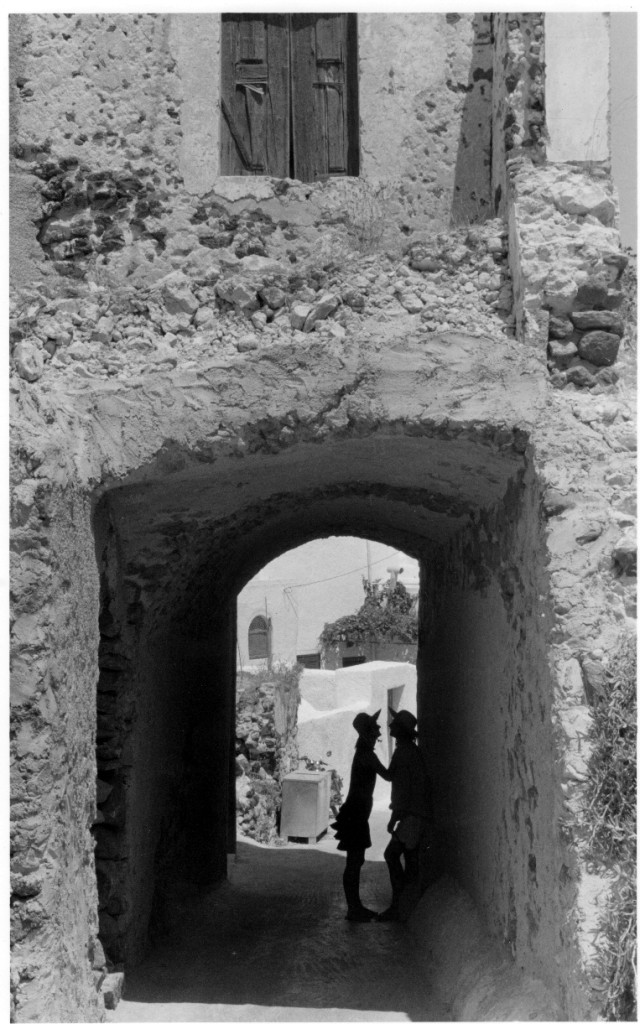

With a camera, I learned that the world was mine for the taking. I could capture the image of any person on the street, any building, any car, and any tree, and in so doing, claim them as my own. The adage “beauty surrounds you if you look hard enough” was no longer a cliché but a truth. How could I not have seen it before? The films “Gone with the Wind” (http://www.rafsy.com/films-1920s-1950s/gone-with-the-wind-another-day-another-chance/), “Dr. Zhivago,” and “The Killing Fields” depict the ravages of war, and there is nothing uglier than war. Yet when viewed through the lens of an artist, the silhouette of a man and a woman and a galloping horse against a city in conflagration adopts an operatic grandeur. That is what the world is: a film in the making, each of its seven billion people cast in the roles of writer, director, and actor.

I couldn’t get into still life photography as a result. Just as with drawing, I preferred people. You could argue that an object has stories to tell. We see those stories from the moment we awake every morning in the objects that surround our room, in the very bed we lie on. Nonetheless, an object would be devoid of its stories if it weren’t for the human hand that had touched it. That was why of all the photographers whose works Peter introduced in class, I responded to those who focused on people: Steichen, Salgado (http://www.rafsy.com/films-2000s-present/the-salt-of-the-earth-through-the-lens-of-love/), Eisenstaedt… Gloria Swanson’s diamond luminous eyes behind a butterfly veil; Amazonians, clothes tattered and soot capping hair, numbering in the thousands as they toil in mountainous terrains like Babylonian slaves in a shot reminiscent of “The Ten Commandments”; a sailor and a nurse in Times Square embraced in a Liberation Day smooch – these images haunt me still.

I could have been the next Robert Doisneau or Milton Greene. My name might have been in bylines beneath pictures in Time and Newsweek. I could have been awarded a Pulitzer for a photo essay on Typhoon Haiyan published in The Washington Post. Not only did I have a good eye, but I also had the patience. In the pre-digitalized age of the 1980s, producing a print required hours in the claustrophobic environment of a darkroom, with as long as 45 minutes in a cubicle spent yanking a film out of its shell, adjusting it on a spool, and enclosing the spool in a canister. As easy as the procedure sounds, it was not. Getting the film onto the spool was a tactile enterprise; exposure to light, no matter how faint, destroyed the roll of celluloid. In addition, I had to ascertain that no part of the film was in contact with any other; a pair of images could be damaged when stuck together while submerged in chemicals. Even so, what a bounty when I got it right, a feeling like no other. I’m sure you all know what I’m talking about: nothing is ever a win unless we slave over it.

I could have been the next Robert Doisneau or Milton Greene. My name might have been in bylines beneath pictures in Time and Newsweek. I could have been awarded a Pulitzer for a photo essay on Typhoon Haiyan published in The Washington Post. Not only did I have a good eye, but I also had the patience. In the pre-digitalized age of the 1980s, producing a print required hours in the claustrophobic environment of a darkroom, with as long as 45 minutes in a cubicle spent yanking a film out of its shell, adjusting it on a spool, and enclosing the spool in a canister. As easy as the procedure sounds, it was not. Getting the film onto the spool was a tactile enterprise; exposure to light, no matter how faint, destroyed the roll of celluloid. In addition, I had to ascertain that no part of the film was in contact with any other; a pair of images could be damaged when stuck together while submerged in chemicals. Even so, what a bounty when I got it right, a feeling like no other. I’m sure you all know what I’m talking about: nothing is ever a win unless we slave over it.