Image courtesy of 121clicks.com

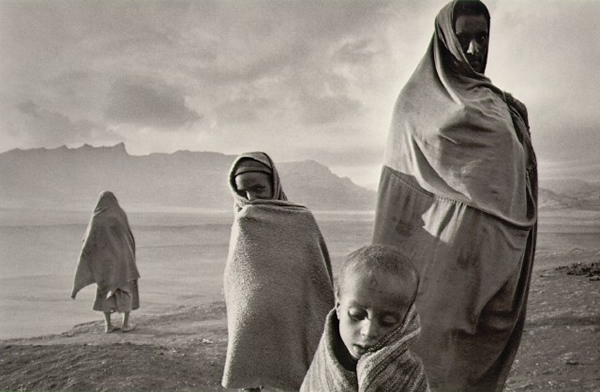

Photographer Sebastião Salgado has said that he is not an artist; an artist makes an object. He calls himself a storyteller. With the camera as his medium of narration, he has occupied news pages with images of global issues ranging from the famine in Ethiopia to the slave labor of Brazilian mine workers, from oil drills in Kuwait to the Yugoslavian Siege of Bihac. True to the creed of storytelling, Salgado focuses on people. We humans have created the world as it is today. Although we credit ourselves for the breakthroughs of space travel and the internet, the destruction that has been heaped upon earth is largely of our doing, as well. On this, Salgado sheds a light. His pictures aren’t pretty, and rarely is a person smiling. And yet, they are beautiful in their portrayal of will and dignity. Even when prostrate, his human subjects rise like pillars amid a map of rubble. No famous faces here, neither leaders of state nor Nobel laureates for peace. Salgado focuses his lens on the likes of you and me, law-abiding citizens who at any moment can become pawns in a political feud. The photographer may not be making an object, but he is making us feel by relaying to us his vision of the downtrodden, and therefore, changing the way we look at the world. That he doesn’t regard himself as an artist might be modesty. I say he is. One of the best.

Image courtesy of tse3.mm.bing.net

Some things Salgado has seen: corpses along dirt paths like fallen trees in the aftermath of a hurricane; children grimy as sewer rats; and millions of displaced in an exodus towards a promised land that doesn’t exist. We, too, have seen these, in textbooks and journals and in documentaries such as this, “The Salt of the Earth” (2014), and all as scenes from somebody else’s nightmare. Salgado’s, no doubt. The irony in Salgado is that he discovered his vocation of photographic storyteller by chance. He never took classes on the craft nor had he been greatly interested in the scourges afflicting nations across the Mediterranean. He was an economist in Paris in the 1970s when his wife, Lélia, gave him a camera. His first picture was of her, languid on a windowsill against a backdrop of the city line, and out of this tender portrait was born a hunger to record the many faces of love in all the cultures of the world. Love shines strongest when we have lost everything and have only each other. Thus, began a journey that would last to this day to lands where civilizations have collapsed.

Lélia has been partner to Salgado’s passion from the get-go. She quit her job as an architect. He quit his job as an economist. They started a photo studio and worked together in order for him to be the best in the field that he could be. There’s a love story right there, the proverbial “behind every great man is a great woman.” I am a firm believer in the silent influence one has in the success of another, whether the former is a spouse, a friend, or a relation. We have words for this individual such as “muse” and “inspiration.” While for some it can be solitary being at the top, nobody gets there alone. What would Chinese director Zhang Yimou be without actress Gong Li? (http://www.rafsy.com/actors-models-directors/gong-li-the-garbo-of-the-far-east/) Gertrude Stein without Alice B. Toklas? Hubert de Givenchy without Audrey Hepburn? Of his mother, George Washington has said, “I attribute all my success in life to the moral, intellectual and physical education I received from her.” (https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/24983-my-mother-was-the-most-beautiful-woman-i-ever-saw) Spiritualist Deepak Chopra acknowledges several people: “If you want to do really important things in life and big things in life, you can’t do anything by yourself. And your best teams are your friends and your siblings.”(https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/deepak_chopra_599972)

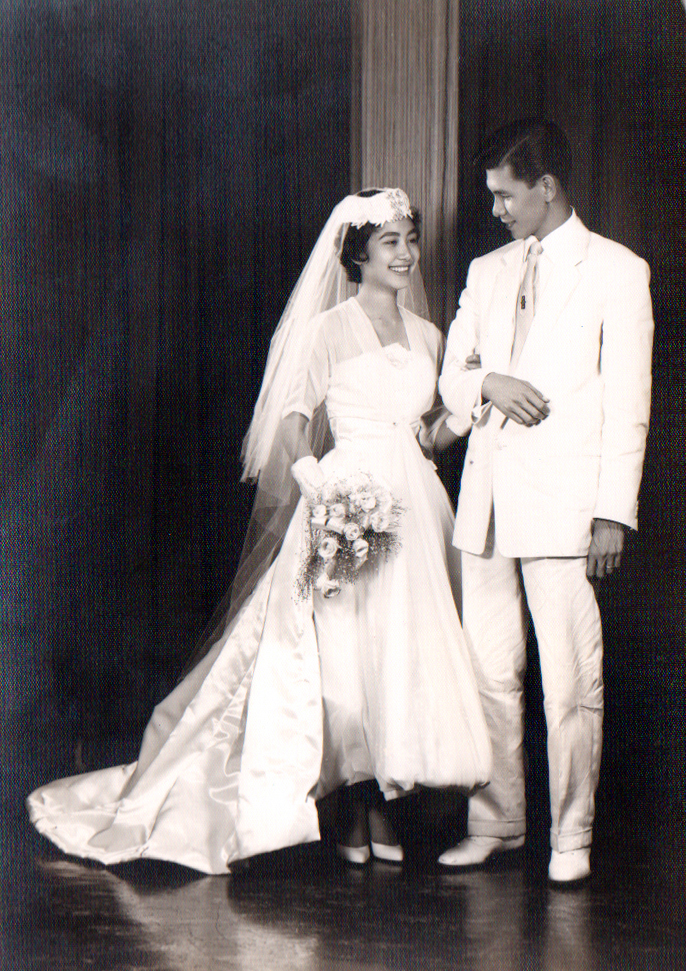

I see this in my parents. My mother has a scrapbook of magazine articles written on her when she was single. Since she was a lovely girl – petite with the Spanish traits of high cheekbones and an aquiline nose – Philippine media relished in using her image to fill empty columns. One magazine features a cover story of her engagement to my father. He was a clerk at the Bank of America, while she was a secretary at Caltex. She would not be working much longer because, as my father is quoted, he would be the protector and sole provider of the family. We today would consider this an old-fashioned view of marriage. Father and mother were wed in 1958. The accompanying photograph of them attests to the respect for tradition prevalent in that era. They are standing underneath a tree – she in a flouncy skirt and do styled after Jean Simmons’s crop; he in white pants and black hair glistening with pomade. My father is at an angle with his back to the camera; only part of his smile is visible. The smile that dominates the shot is that of my mother. As my father holds her hand, her smile is all giving, even worshipful. This isn’t a common photograph of a 22-year-old girl in love. This is a quiet moment in which the bride is entrusting the groom with her future. From that moment on, she would be the guardian of his dreams and ambitions. Old-fashioned marriage aside, it worked.

I see this in my parents. My mother has a scrapbook of magazine articles written on her when she was single. Since she was a lovely girl – petite with the Spanish traits of high cheekbones and an aquiline nose – Philippine media relished in using her image to fill empty columns. One magazine features a cover story of her engagement to my father. He was a clerk at the Bank of America, while she was a secretary at Caltex. She would not be working much longer because, as my father is quoted, he would be the protector and sole provider of the family. We today would consider this an old-fashioned view of marriage. Father and mother were wed in 1958. The accompanying photograph of them attests to the respect for tradition prevalent in that era. They are standing underneath a tree – she in a flouncy skirt and do styled after Jean Simmons’s crop; he in white pants and black hair glistening with pomade. My father is at an angle with his back to the camera; only part of his smile is visible. The smile that dominates the shot is that of my mother. As my father holds her hand, her smile is all giving, even worshipful. This isn’t a common photograph of a 22-year-old girl in love. This is a quiet moment in which the bride is entrusting the groom with her future. From that moment on, she would be the guardian of his dreams and ambitions. Old-fashioned marriage aside, it worked.

Even though my father was frequently on business trips during my childhood, he was an ever present figure. He was home on weekends, tanning in the garden or, for the year we lived in Walnut Creek, picking weeds and mowing the lawn. During the week, he always occupied his seat at the head of the dinner table so that we could have the last meal of the day as a family. If he had to work late, he would call my mother, who would tell us kids to eat ahead while she waited up for him so that she and he could dine together. Then we would watch TV. Our favorite shows: “Hawaii Five-O” and “Laugh-In” in the 1960s; “The Love Boat,” “Charlie’s Angels,” and “Fantasy Island” in the 1970s; followed by “Three’s Company” and “Dynasty” in the 1980s.

For her part, my mother was the classic homemaker. She never missed any school production I appeared in. In the fifth grade, I was cast as an evil stepbrother in “Cinderfellow,” the male version of “Cinderella.” I had my star moment with a monologue delivered amid excessive arm raises. I must have grown between the casting period and opening night because my trousers were so short that the hem was above my ankles. After I took my bow at the end of the play to the applause of the audience, my mother rushed to me, aghast. “Your socks don’t match,” she said. “One is blue and the other is black.” But she was smiling and so was I. It was her responsibility to notice those things.

Image courtesy of gagdaily.com

I always thought my father confided to my mother everything that went on at the office. Only a couple of years ago did my mother say this wasn’t so. For my mother to build the home as a safe haven for her husband and children, they agreed that it was mandatory worries pertaining to the bank stay locked in its vaults. That was the only way my father could stay true to the oath he had made that day under the tree. As a result, we’ve survived everything from kidnap threats to a bank run, and in the 57 years that my parents have been married, my father moved up from clerk to founder of his own bank. The business trips that took him away from us had been difficult for my mother, but she understood the necessity of them; they were part of the dream she had married into.

Sebastião Salgado in “The Salt of the Earth” expresses the downside of success on his own family. While growing up, son Juliano hardly ever saw dad. Nevertheless, this did not diminish the boy’s pride in his father. That Salgado ventured to lands and was privy to experiences people only read about made him a superhero in Juliano’s eyes. Today, Juliano has followed in Salgado’s profession and works as his father’s assistant. Lélia remains by Salgado’s side as editor to his books.

One doesn’t need to make an object to be an artist. Art can be something intangible that is beautiful on account of its power to move us, discernible to our hearts rather than to our eyes. How we love so that our dreams can flourish is itself a vision to behold.

Image courtesy of revistatpm.uol.com.br