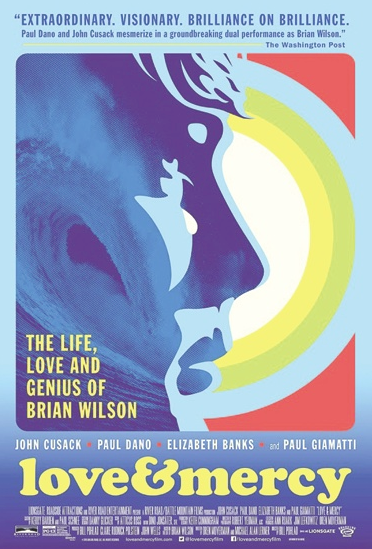

Image courtesy of pinimg.com

California conjures sun and sand, Speedos and surfboards, and yearlong summers high on weed. Girls are blonde. Guys are buffed. Flip-flops drag on pavements, and tank tops show off tans. It’s a utopia of indolence. Ever since the Gold Rush, the American West has been portrayed as the epicenter of bacchanalia. When the earthquake and fire of 1906 razed San Francisco, the East Coast old guards tagged the destruction a retribution for the city’s fabled whore houses, and 60 years later, the land where the Golden Gate shines was again the subject of judgment for its Flower Power Movement. Protesters of the Vietnam War wielded peace signs in the sky. Hippies packed streets, jobless and strung out on acid. Somewhere in the pandemonium, a new sound was born, music that was a scream for rebellion, though not with the brand of activism associated with the tunes of Bob Dylan. For The Beach Boys, being young was a dance by the ocean. “I Get Around,” “Help Me, Rhonda,” “Surfer Girl,” and “Fun, Fun, Fun”… the song titles alone intimate the spirit of effervescence. Don’t let the frivolity fool you. Brian Wilson, songwriter and lead singer to the band, went through angst to create all that we hear today as The Beach Boys.

Image courtesy of squarespace.com

“Love and Mercy” (2015) chronicles to what degree Wilson struggled with both mental and emotional ailments, and they were intense. We’re talking child abuse and hallucinations. As a boy, he lives in a house where violence echoes within its walls. His father, Murry (Bill Camp), would punch him senseless, sometimes in the ear, which leads to his being partially deaf, and later, as a rock n’ roll legend, Wilson falls under the influence of Dr. Eugene Landy (Paul Giamatti), who pumps him with pills meant to medicate his alleged schizophrenia when, in truth, he is of sound mind. The drugs are a method of manipulation, allowing Landy access to the musician’s will for him to amend so that he would be the inheritor of a massive estate. “Love and Mercy” alternates between a young (Paul Dano) and a middle-aged (John Cusack) Brian Wilson. This so we see that despite the years of treachery, his star ascends and his genius evolves, proof that creative diligence cannot be squelched.

For those of us who lacerate over a part of ourselves that we’d like to share with the world, “Love and Mercy” offers assurance. To make greatness look easy isn’t easy. So deceptive is the effort that the most profound message can come in the sparest package. It’s like a diamond ring in a small box versus a vacuum cleaner in a big box. As the Brian Wilson biopic shows, The Beach Boys repertoire was a product of grueling hours in the recording studio, Wilson’s genius notwithstanding. One scene has Wilson perfecting the string instrumentals to “Good Vibrations,” the musicians driven to exhaustion by his whip cracking of “again… again… again…” and in another, he proves that more than lyrics to a pop/rock number, the words “good vibrations” encompass a life philosophy when he cancels a session because the venue gives him bad vibes, a decision that costs him $5,000 for each musician present. A poignant moment occurs with a backup player. The man claims to have performed with the best, including Sinatra, but it is the numero uno Beach Boy whom he considers “touched”; Wilson is a vessel of melody, one of such transcendent talent that he stands above the others in a category of his own. Still, our hero works his ass off.

Image courtesy of presscdn.com

This creed of applying our all to produce the best that we can by the grace of simplicity has been ingrained in me over the years as a writing student. In high school in the Philippines, I suffered from verbal diarrhea. I wrote essays that were a jumble of highfalutin words plucked from the Thesaurus, believing that only by simulating the tone of a 19th century scrivener was I able to create anything of substance. I suppose this happens to all of us once we discover the command of words, especially when the reading syllabus consists of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville. The denseness of language might have worked during their time; journals that serialized their writings paid them by the word. For my generation and my culture, and for the sake of being myself, subscribing to the dictum “less is more” would have been to my advantage. College ultimately taught me to trust in my own voice, which presented its own set of difficulties. What a hard task it is to scratch off all the guck in order for me to surface. I’ve often been stuck with a paragraph that has left me in doubt of whatever message I’m attempting to impart. This is why workshops and seminars exist. Even then, they offer no solution given the number of attendees, each with one’s own opinion. Writing remains a stumping experience.

Herein lies Brian Wilson’s gift. A tune needs to be catchy, its accompanying lyrics quick to pick up yet reflective of ourselves, a story of a universal emotion:

Wouldn’t it be nice if we were older, then we wouldn’t have to wait so long. And wouldn’t it be nice to live together in the kind of world where we belong… Maybe if we think and hope and pray, it might come true. Baby, then there wouldn’t be a single thing we couldn’t do. We could be married and then we’d be happy. Wouldn’t it be nice. You know it seems the more we talk about it, it only makes it worse to live without it, but let’s talk about it. Wouldn’t it be nice. Good night, my baby. Sleep tight, my baby.

No space for verbal diarrhea here. The hankering of a young couple to be free to love is straightforward, infused with a desperation that invokes Romeo and Juliet. (http://www.rafsy.com/films-1960s-1990s/romeo-and-juliet-till-death-and-beyond/) “Good night” and “sleep tight” seem to allude to an eternal union in another world. Whoever thought a commonplace nightly greeting could bear such an implication?

Image courtesy of the-artifice.com

The challenge of composing a simple and memorable song is tantamount to the challenge a novelist faces in composing a simple and memorable first sentence. Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins Vladimir Nabokov begins in “Lolita” and in so doing introduces us to a story of lewd and emotional obsession. In “Love in the Time of Cholera,” Gabriel Garcia Marquez, rather like a ship captain detailing in one breath the course of a voyage, wastes no time in filling us in on the 350-page journey to follow: It was inevitable: the scent of bitter almonds always reminded him of the fate of unrequited love. Here’s one first sentence so elementary that any of us could speak and write it at any moment: In those days cheap apartments were almost impossible to find in Manhattan, so I had to move to Brooklyn. This belongs to William Styron in “Sophie’s Choice.” Plain as it is, it sets the stage for a tale of madness, passion, and suicide surprising even to the narrator given that the tragedy happens in a neighborhood we more associate with domestic monotony than with drama.

“Love and Mercy” sheds insight into the mind of an innovator and an artist, and it is frightening to see what cruelty Wilson endured. He reached his zenith with “Good Vibrations” in 1966, after which he spiraled into a pit of drugs and alcohol, culminating in 17 years under Dr. Eugene Landy’s thumb from 1975 to 1992. Wilson could have spent the rest of his life in the shadow of his former glory if not for Melinda Ledbetter (Elizabeth Banks), a car salesgirl in whom Landy meets his match; she slaps him with a subpoena upon discovering Wilson’s papers that the doctor has been counterfeiting.

Ledbetter and the genius have now been married for 20 years. Though the man always had drive, through his wife’s love and mercy, he resumed his creative calling. Brian Wilson continues to write songs to this day, and just as it was when The Beach Boys were a chart topper, his productivity is a matter of labor.

Image courtesy of blogspot.com