Image courtesy of i.telegraph.co.uk

Hollywood has a penchant for envisioning the future as a wasteland of destruction. When the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima, little did we know that a black cloud would loom over the imagination of every man and woman born thereafter. Fact might not be far from fiction. The Rodney King riot that erupted in Los Angeles in 1992 resulted in cobwebs of smashed glass on building fronts, flames in the night, and fallen supermarket merchandise from toilet paper to ketchup turning aisle floors into a rocky terrain. Soldiers in black helmets patrolled the streets, their batons raised in attack formation. Citizens of every ethnicity tore at each other like beasts in the wilderness. For a week, Los Angeles spun off its axis. “Blade Runner” (1982) predicts this bedlam, only the Los Angeles of “Blade Runner” is set in 2019. The city’s demise started 27 years too soon. With nuclear arms on the rise in regions across the globe from North Korea to Israel, and with terrorists annihilating civilizations, the rest of the world in the second millennium is just as doomed.

Image courtesy of wordpress.com

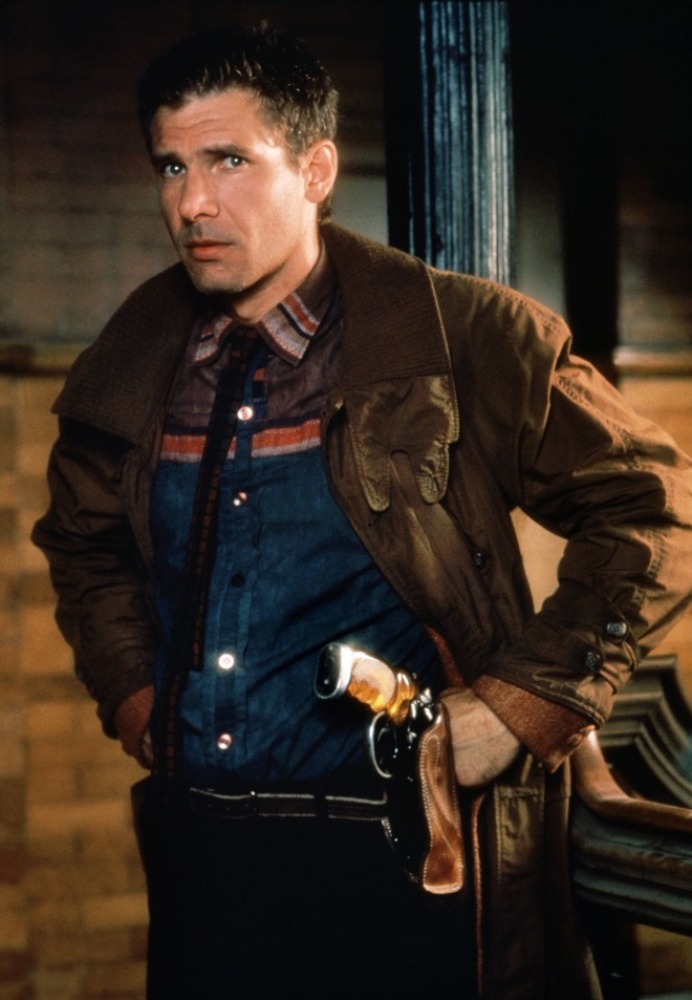

If Armageddon is the only factor that unites humanity, we wonder why the laws that protect us from theft, murder, and civil violations of all sorts that rob us of our right to be. No sense in waiting for a bomb to do to us what we’re able to do to each other. It’s with this cynicism that Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) wears a frown. He’s a Blade Runner, a government assassin whose target is Replicants, the term for androids in this dystopian microcosm. Humans created Replicants. The master engineer is a scientist named Dr. Tyrell (Joe Turkel). Their purpose is to work as slave labor in the construction of colonies on other planets, where our species is to flourish onward once the world ends. Molded after our image, Replicants deviate from us in two respects – the capacity for emotion and longevity. Their life span is four years.

As is the case with the oppressed, the Replicants have mutinied, marking them as criminals to be terminated. Four of them have managed to return to earth to seek more life from their maker. Although not as lethal as the A-bomb, they are lethal even so. In their desire for a prolonged existence, they kill in a process that involves the crushing of the skull and the gauging of the eyes. This because Replicants resent us humans for possessing a brain layered with memories that trigger emotions expressed through the one part of our body that speaks when words fail us.

Image courtesy of blogspot.com

Deckard himself is a man of few words, a futuristic version of the frontiersman of yore in the vein of John Wayne and Gary Cooper. Like all silent types on a mission for justice, he faces his greatest challenge in an affair that involves the heart – a Replicant named Rachael (Sean Young). While Deckard has no qualms about killing the others, Rachael is different. She is not part of the band of renegades. She is an experiment implanted with memories and who goes AWOL from Dr. Tyrell. Rachael also happens to be statuesque with lips as red and lush as cherry, luminous skin, and hair the black of black onyx styled in retro-1940s bouffant – a cross between Betty Grable and Wonder Woman. Aside from being drop dead gorgeous, the tricky thing about Rachael is that she doesn’t know she is a Replicant.

“I dreamed music,” Deckard tells Rachael in one pivotal scene. She says, “I didn’t know if I could play. I remember lessons. I don’t know if it’s me or Tyrell’s niece.” Rachael’s doubt notwithstanding, Deckard only sees her. “You play beautifully,” he says. They are sitting at a piano in his place. A moment earlier, she saved him from death by shooting a Replicant who was about to empty his skull sockets. She knows now that she is not human, that her memories could be those of another; Deckard told her the truth of herself. Thus, she is on the lam, has nobody to turn to except Deckard. She asks him if he would hunt her down if she were to disappear north, wherever north may be. He tells her no. He tells her he owes her. As he lies in repose exhausted from a day that could have been his last, he falls asleep then awakes to the gentle tap of the piano keyboard. Here they are, man and woman, side by side, two loners connected in chaos. Deckard brings his face close to hers. She runs, but opens the front door only partially when Deckard slams it shut, pushes her back into the living room, where he demands one thing of her unique among living creatures as proof of the possession of a soul: “Say kiss me.”

Image courtesy of 3.bp.blogspot.com

That Rachael falls under Deckard’s spell is no shock. The shock is in Roy (Rutger Hauer), the leader of the Replicant deserters. He is Deckard’s last target. In a fight to the finish, they smash walls, break fingers, and leap building tops. Roy is the victor. As Deckard shrivels against a post in surrender of his fate, the world is drab and wet from a cloudburst. But rather than meeting his own maker – whether his maker be God or science or some omnipotent force that orchestrates the law of evolution – Deckard confronts a distraught foe. Roy sits before Deckard like a sage opening the gate to knowledge, his eyes not murderous but sad, and with Dr. Tyrell having denied him more years, he recites his own obituary: “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the darkness at Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time like tears in rain. Time to die.”

Why, Deckard wonders, why is this most deadly of Replicants allowing him the blessing of what he so direly wants for himself? Perhaps Roy isn’t a monster after all, for although memories may not have been implanted in Roy, the memories he did acquire from the day of his inception were rich enough to stir in him the very human feelings of loss and mourning.

Image courtesy of c7.uihere.com

And so Roy dies, Deckard lives, and Rachael runs north. Our hero stays loyal to his oath. He doesn’t follow Rachael. He goes with her. In this most dichotomous of pairings, we understand as “Blade Runner” comes to an end that Armageddon is not what unites humanity. It is the fight for survival. For all our technological advancements and quest for immortality, the warmth of another’s touch is what sustains us, and the sensation of completeness upon witnessing a light enliven a heart as the person whose eyes we are looking into sees us in return as dear and indispensable.

Love has the power to build pyramids, palaces, and civilizations. Love can compel a king to relinquish the throne and drive a queen to end her heartache with a serpent’s venom. Love is the thread that joins every era through the infinite course of history, from the biblical past to the space age present and beyond into the apocalyptic future.

Love is the miracle that turns an android into a human being.

Image courtesy of blastr.com

Do you mind if I quote a few of your posts as long as I

provide credit and sources back to your site?

My blog is in the exact same niche as yours and my users

would really benefit from some of the information you provide here.

Please let me know if this alright with you. Thanks!

That would be all right. What is your blog site?