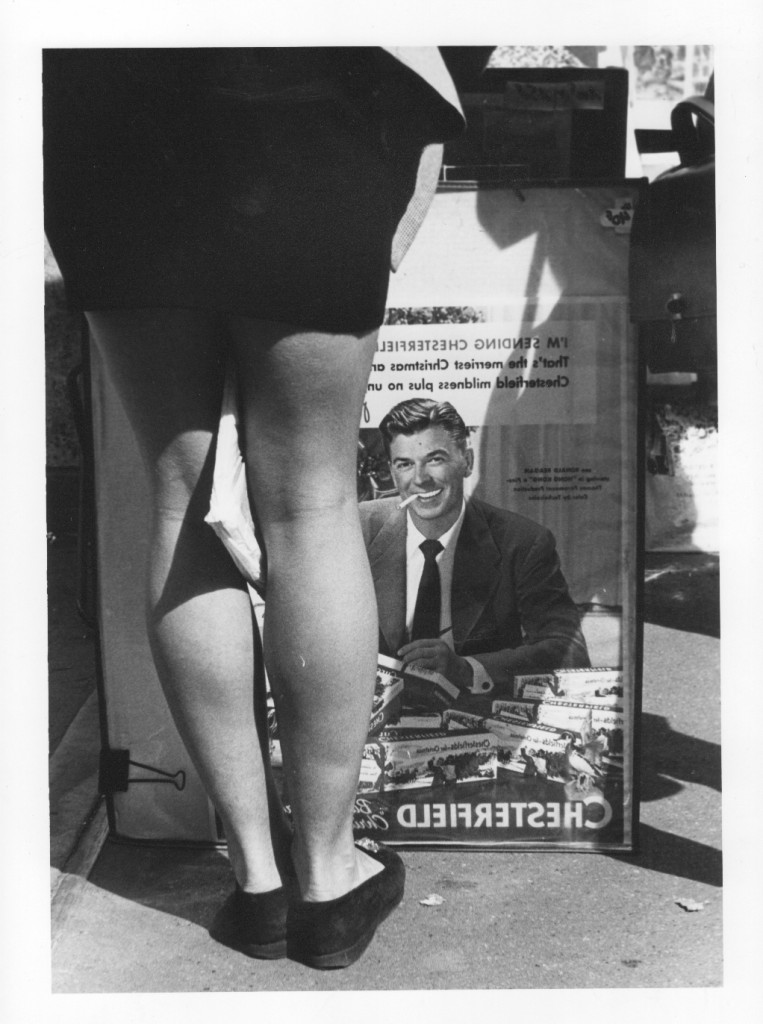

Image courtesy of i.stack.imgur.com

I once wanted to change my name from Juancho Chu to Wittgenstein Walcher H. Rockefeller van Stausen Smith (sometimes Smyth) VIII. I was twelve years old and living in Manila, in a brick house that I imagined sometimes as a castle, sometimes as an ocean liner, a large-windowed house with twelve air-conditioners to keep it as cool as a Hollywood mansion. I played with bath towels as a queen’s headdress. The seal of envelopes to my collection of Hallmark stationery tasted like a rose. In my heart was a girl to whom Hardy Boy Joe, Shaun Cassidy, serenaded “Da Doo Ron Ron.” But the idea for my American name came to me not from TV or some fantastic thoughts I might have had of another world, another life: I was an accomplice to the secret love affair our family maid was having with the neighborhood watchman.

“I’d like to know his name,” my father said one morning over breakfast. He was commending the watchman for his sense of duty. Sometime at dawn my father had gone to the bathroom. He glanced out the window and from the end of the street the watchman appeared on his motorcycle, making his rounds. The watchman stopped upon seeing a light in our house turned on, then drove off minutes later when nothing more suspicious happened.

“James Cagney,” I said.

My father laughed. He turned to my mother who grinned at the sight of his thick eyebrows twitching like caterpillars. Her lips were as pink as faded poinsettias. “James Cagney, eh,” he said.

“You eat too much,” said my mother. “You imagine things too much. Take it easy.” My mother monitored how much food I put on my plate, counting the servings of rice and pieces of pork sausages. I was a kid without a neck. My stomach blocked my view of my feet.

“James Cagney,” I said again.

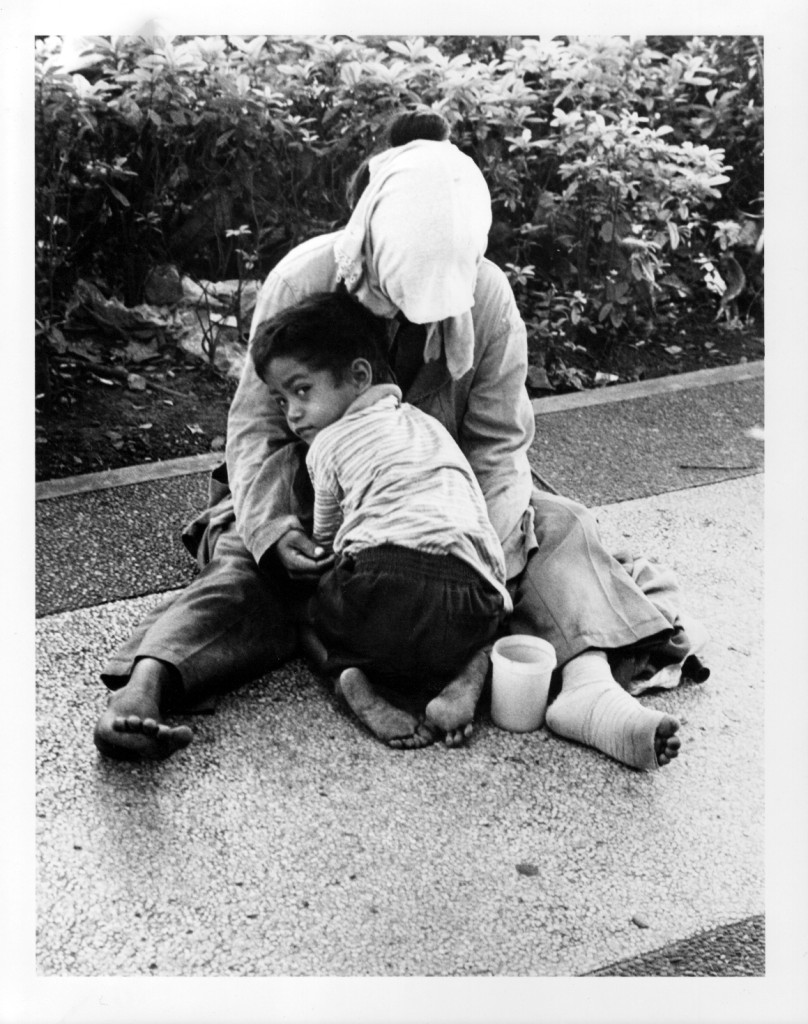

It’s true. The watchman’s name was James Cagney, James Cagney Alejandro. I had met him for the first time four months back. My family and I had just returned from our yearly summer trip to San Francisco, where an aunt and an uncle lived in Atherton, a town an hour’s drive south of the city. During the trip we saw Yankee Doodle Dandy on TV, so what a coincidence that I would meet an actual James Cagney. Like the original, the watchman had a pug nose, bulldog eyes, and a boxer’s build. He was half-American, white as Yankee Cagney with nails clipped and polished and strong hands. He and our maid Malen were talking at the white gate of our house. My father had already left for work and my mother had stepped out to the beauty parlor. I was roller-skating on the driveway, oblivious to the company Malen was keeping. She and James Cagney seemed to be engaged in nothing more than friendly talk. They weren’t holding hands. Neither one of them was smiling shyly nor glancing furtively around to see if anybody aside from me was witnessing any secret flirtation — signs of love I knew about from watching my two older sisters and older brother when they brought dates home. Although the gate was open, James Cagney stood outside while Malen never went past the premises of our home. She leaned against the gate, one foot on its tip behind the other. She was a large woman, Malen. Her waist was as wide as her hips. She had a double chin and the hair of cauliflower curls on her head made her taller than James Cagney. That alone made an affair between them silly. What man wants a woman larger than he is?

Image courtesy of pinimg.com

I skated down to them.

“This is Juancho,” Malen said.

“Like his daddy,” said James Cagney. “So Chinese.”

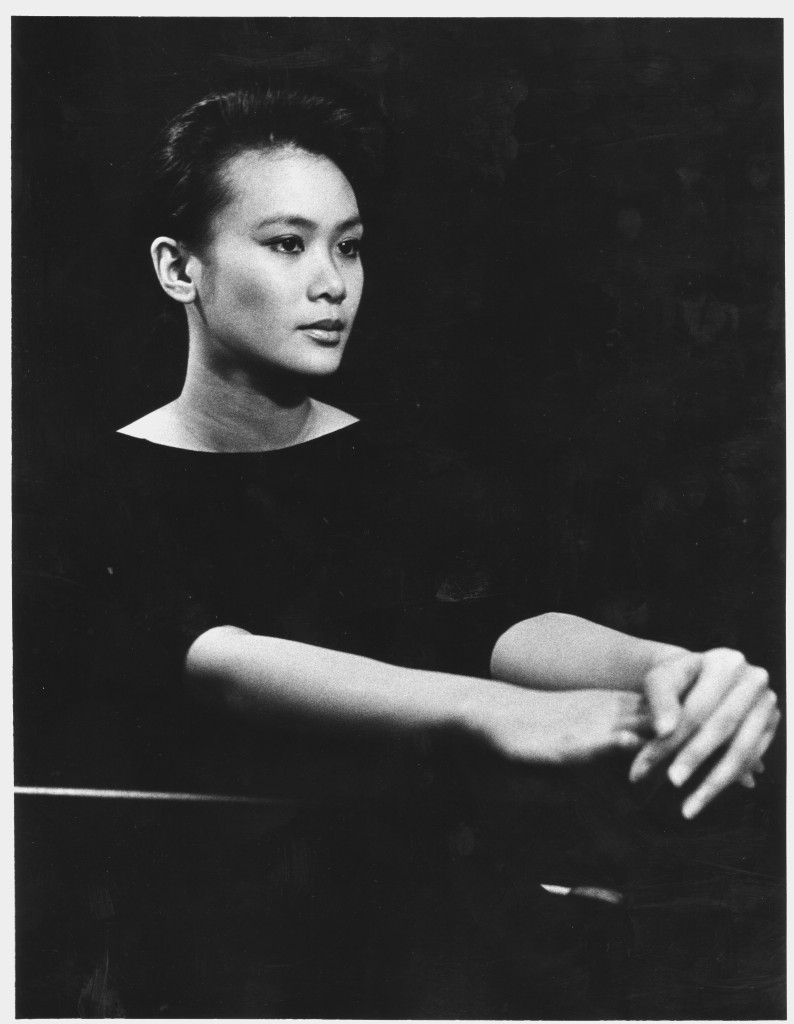

His smile, it had a sincerity to it, as if he truly were glad to meet me and had been wanting to for a long time, and his voice, he sounded like a boy — my seventeen-year-old brother Bach had a deeper voice — and yet, in his blue uniform, James Cagney wasn’t anybody that a car could run over. His forearms were Popeye big. His trousers fit his thighs like tights on Captain America. Face to face with James Cagney, I must have seen what Malen saw. The sky was no longer a sky; it was a lightless space with neither clouds nor birds. The trees lining the pavements, the other massive houses behind spiked gates, Malen herself — everything fell beyond the periphery of my vision. James Cagney, James Cagney Alejandro.

James Cagney left with a “See you later” to Malen. As he drove away in his motorcycle, I asked Malen when he’d be back. “I don’t know,” she said.

He was back the next day. He and Malen stood on the same spot at the gate. Again they kept their distance as I roller-skated on the driveway. “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” I said as I approached them. They looked at each other and laughed. Malen girlishly covered her mouth. I had never seen her laugh that way before.

“What’s that Yankee Dododa?” asked James Cagney. James Cagney Alejandro had never heard of his namesake.

“You have a movie star’s name,” I said. “Everybody in the States knows your name. How did you get a name like that?”

Malen gave another girlish laugh, her head bowed as if her hand were a fan she was hiding behind. “The same way you get your name.”

I was standing closer to James Cagney now, right beside him. He smelled of meat and heavy cologne. He wore a black cord that emphasized the thickness of his neck. I touched his gun holster.

“No. That’s dangerous,” he said.

I held on tighter.

“Uh, uh,” he said. “No.”

Image courtesy of salemwebnetwork.com

I let go. I glanced at his belt buckle. Square with a silver sheen, it was like a miniature shield. “Where did you get this?” I held it on the tips of my fingers.

“My uniform,” he said, looking down at where my hand was and then at me. I looked up from the buckle and into his eyes.

“Juancho, you roller-skate some more,” Malen said.

James Cagney came nearly every day. My father left for work each morning at eight. My mother had no fixed schedule, yet James Cagney would knock at our gate fifteen minutes after she would leave for someplace, no matter the time of day. Some days my mother had no plans for an outing and so James Cagney never came. Whether Malen saw James Cagney or not, she was always humming a tune.

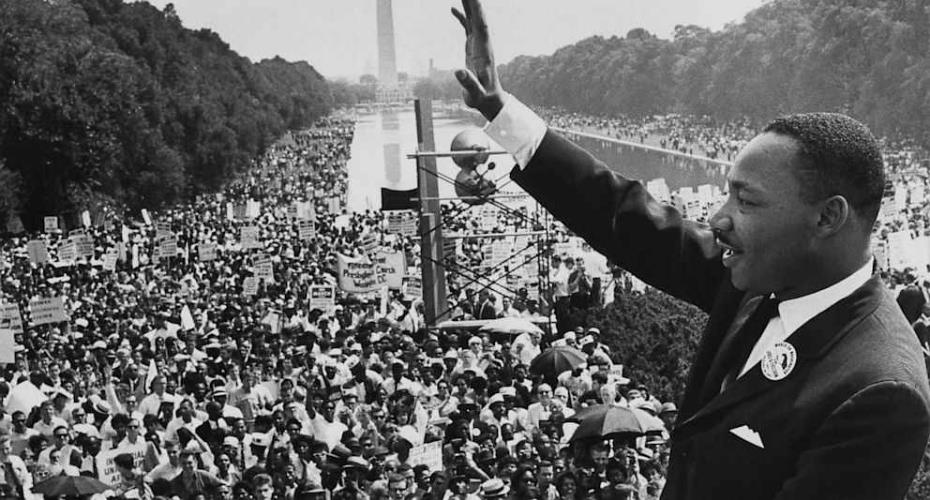

One afternoon I was alone in the back terrace, at the lunch table looking through cut out magazine pictures of “Charlie’s Angels,” which I collected in a Hallmark stationery box. The only sound was the snip snip of the gardener’s scissors while he pruned the hedges that lined the garden wall. It was a distant sound, almost an echo, for how far and small the gardener was across the sprawling green stretch of grass. All I saw of him was his straw hat, which he hid beneath to block away the sun. The ceiling fan above me chugged lazily to shoo away the flies. My glass of calamansi juice was sweating with dew. And then Malen’s humming from the kitchen at the end of the terrace drifted to where I was. Her voice was full and calming. She was humming a tune I had never heard before and which I have never heard since. It was a kind of lullaby that for a fleeting moment froze the hot garden into an image from a dream. I didn’t know I was hearing Malen. I didn’t even know she could carry a tune. For the first time I thought of how Malen spoke. She had a wispy voice, one I had never heard her raise. I had never seen her in any outburst of emotion. She was neither happy nor sad. She was just there, a maid who silently dusted the furniture and served us our meals.

Malen came out of the kitchen with a tray of bread pudding. She laid the tray on the table and picked up a photograph of the Angels. Their hair flipped back and hands clasped together in prayer, they were modeling daywear: blonde Jill in a tennis outfit; Sabrina in a secretarial skirt and blouse; Kelly, my favorite Angel, in a bikini. Kelly’s hair was nearly as black as mine and I could see a little bit of her tan on me.

“Who do you like?” I asked.

Malen shrugged her shoulders.

“Choose one.”

Image courtesy of cdn.collider.com

She gazed at the picture a few seconds more then pointed at Sabrina. Of the Angels, Sabrina was the least dolled up. She had a bob and her skirt covered her knees.

“You want to look like her?”

“Why?” Malen said. “I’m not American.”

“I mean thin like that.”

She shrugged her shoulders.

“They’re all so pretty,” I said.

“Yes,” she said, though without much concern.

“Ape Woman,” I said, helping myself to the bread pudding.

Normally Malen would have pursed her lips to my taunt, but this time she grinned. She went through my cut out pictures of the Bionic Man and Woman, Hardy Boys Shaun Cassidy and Parker Stevenson, and more Charlie’s Angels. The gardener was watering the plants now, spraying the leaves of trees taller than the house. Malen hummed her song.

“James Cagney — he’s American,” I said. “Tell me, how did he get his name?”

“His mommy was American,” Malen said. She seemed to look into herself rather than at my Hallmark box of pictures. Her eyes were foggy, not tearful but layered with emotions I was just beginning to understand. “He was named after her daddy. Her daddy’s name was James Cagney. Good name for him. Macho. Strong.” Malen flexed her forearms. “What you think? He’s macho, huh. Handsome.”

I flexed my own forearms, but it stayed small. I tucked in my stomach, but still it bulged over my belt loop. I didn’t want my bread pudding anymore. “Yes,” I said with Malen’s tone of indifference. That’s when the idea for a new name came to me. I didn’t even think long about it. One blink and it spelled itself out before me: Wittgenstein Walcher H. Rockefeller van Stausen Smith (sometimes Smyth) VIII. I don’t know where Wittgenstein came from. Walcher I derived from Walton, as in “The Walton Family,” and H from Henry VIII, the king I was fascinated with by virtue of his having ordered the beheading of two of his six wives. Rockefeller was the most famous American name I knew, Smith the most American, and van Stausen rhymed with Beerhausen, a brand of beer so heavily promoted in the Philippines as Germany’s No. 1 drink when in reality it existed nowhere else in the world but in the Philippines. “How nice to have a nice name,” I said.

Image courtesy of personalsuccesstoday.com

“Juancho Chu,” said Malen.

“Ape Woman, be quiet.”

“What’s wrong with that? That’s your name.”

I pushed the tray of pudding away. “I don’t like this.”

“But this is your favorite,” Malen said.

“Next time I’ll have… I’ll have spinach.”

“Spinach?” She laughed. “What’s happening to you?”

From that day on I stopped drinking soft drinks, forbade my aunt and uncle in San Francisco to mail me packages of Hershey’s Kisses and Nestle’s Crunch, and left the dining table hungry. I was nauseous and weak half of my waking hours, yet never too weak for a set of toe touches and jumping jacks. Nor for another round of masturbation. Since fat is white, I reasoned that whatever it was my penis was ejaculating must be fat, and so I believed that the more I went at it, the thinner I’d be. There I lay on my bathroom floor, morning, noon, and night, rubbing the fuzzy toilet seat cover in between my legs. Those Popeye arms, those Captain America thighs, the life that lay hidden beneath that gleaming belt buckle — me, too, someday.

“He’s losing weight,” James Cagney said to Malen toward the end of summer.

Hardly any light was in the sky — everything was gray — and yet how blinding James Cagney was with his wavy hair and his eyes that ran the length of my body. His security hat was on the handle of his motorcycle. Malen was standing in between his legs. She rested one hand on his thigh as he sat on his motorcycle, while with her other hand she brushed his brown hair back. None of the neighborhood watchmen had hair as light as his. Neither did any other civil servant throughout Manila. Under the sun, James Cagney never got dark. On a cloudy day he brought a breath of cool wind to a humid drizzle. James Cagney could have passed as one of the foreign residents of the neighborhood.

“I don’t know what he’s doing to himself,” said Malen.

I leaned against the tree that they always rendezvoused beneath and tightened the waist of my shorts. I had lost ten pounds.

“You might disappear,” James Cagney said to me.

I twirled a finger in my hair to form a wave like his. “I’m growing taller,” I said. “I’m going to get the kind of shoes you have.” He wore these black elevator boots.

“Not yet,” he said. “When you’re big already.”

James Cagney took Malen’s hand. Malen looked at me from the corner of her eye. He whispered in Tagalog, “Never mind. He doesn’t say anything, does he?” She said no. And they went on whispering. Mostly they stayed frozen in their position, gazing at and holding each other.

“It might rain,” I said.

They didn’t say a word.

“The sun might come out,” I said.

Still, no word.

“Mommy’s car’s coming.”

Malen jumped back from leaning on James Cagney’s lap. A car passed by, but it wasn’t my mother’s.

“Juancho, you go inside,” Malen said.

Image courtesy of spirituality.org

“I don’t want,” I said. That wasn’t what James Cagney wanted either, I didn’t think. But then he didn’t contest her. He didn’t even seem to hear her. He simply kept his eyes on her, as if with one blink he would lose sight of her once and for all.

“Bye.” I waved a hand up to James Cagney’s face.

He gave me a quick, impersonal, good riddance nod.

From the den window, I watched the two lose themselves in a private world of hand clasps and soft strokes. As large as Malen was, she was suddenly demure in the worshipful way she looked into his eyes, in the bow of her head. Her head was so low that her chin pressed against her chest.

Once classes started in August, I no longer saw James Cagney in the afternoons, but I continued with my diet. In a course of two months I lost a total of thirty pounds. I knew Malen and James Cagney continued their afternoon trysts because she would always be humming, not loudly but softly, softly as one thoughtlessly hums a tune while adrift on a wave of some beautiful memory.

“Why don’t you shut up,” I said one day when I was losing my head over some math problems. Malen was serving me my afternoon meal. We were in the back terrace and again the gardener was creating his own music of snipping weeds and watering trees. All of a sudden Malen was quiet. The expression on her face didn’t change. She still looked happy; she had this smug smile that said nothing in life could go wrong. I pushed the tray of food away from me. “I don’t want this salad shit.”

“But every afternoon you eat this. You said you like vegetables only.”

“It taste like dog caca.”

Finally the corners of Malen’s lips and big eyes dropped into a sad face. “Why talk like that?”

“Because you’re ugly.”

She didn’t say anything. She just kept looking at me with that sadness.

“James Cagney doesn’t really like you. You’re too ugly. He only sees you because we pay you good money.”

Malen quietly picked up the tray and headed back to the kitchen behind us.

I threw my math book at the heels of her feet. “Ugly,” I said. “Oomph! Oomph! Monkey face. Monkey face.”

Image courtesy of wordpress.com

She placed the tray back on the table, picked the book up from the floor, and placed it in front of me, opened to the page that I was working on. Then she returned to the kitchen, tray in hand.

I threw the book at the kitchen door then ran to my bathroom. I lay on the floor, rubbing the fuzzy seat cover in between my legs. James Cagney was stroking my hair, smiling into my eyes, touching my lips. Or was it really me with him? My hair is lead black. My eyes are the black-brown of a castana nut. Whoever it was that I imagined as myself was as fair skinned as James Cagney, as brawny and as cool. We were surrounded by darkness, no sun, no blazing sky. Yet how hot it was. I’m from a country where under the March sun sweat drips down your forehead as mercilessly as wax down a candle, lizards squiggle across hot white walls, and papayas grow the length of a dish tray. Cold is the hum of an air-conditioner to lull you to sleep, your lips around a tangerine-flavored icicle stick in mid-afternoon. It is the snow-capped dreamscapes you’ve only seen in American Christmas specials on TV. It is dry ice in your kitchen sink creating mist under running water.

That night James Cagney made his midnight trip to our house. I knew that he came nearly every midnight because some weeks before, the creaking of the back gate woke me. Only this night, the night for which my father would commend James Cagney for being a dutiful watchman, would be his last.

“He was here to see Malen,” I told my parents the morning after over breakfast. “They’re having an affair.”

“Eh,” said my mother. She forbade liaisons between the domestic helpers and outsiders. An outsider could break into our home and steal or kill. “Malen’s an old maid. Look at her. She doesn’t do things… like that.”

The whole family would find out the truth that Monday. James Cagney’s wife came banging on our gate. A girlishly thin woman, she screamed with a sparrow dull cry for Malen to come out just as I was boarding our car for school. In a huff, Malen rushed out of the garage and down the driveway, barefoot. Her feet against the ground made hard slapping sounds. The two were yelling all sorts of stuff, but the only words I could get were from James Cagney’s wife: “You’re the one? You’re so ugly. Ugly and fat.” Malen’s fluff of curly hair stood on their ends. In the five years she had been with the family, never had I seen her so angry. Not even with my own taunts of Ape Woman did her lips quiver so and her chest heave. Malen seemed to grow in size the way cartoon depictions of children growing into adults do. She dragged James Cagney’s wife onto the driveway and pulled at her bun. “Ugly,” James Cagney’s wife kept screaming, throwing punches into the air in an attempt to loosen from Malen’s grip.

I didn’t budge from my seat on the car trunk. I tucked in my stomach. I wasn’t fat. No, I wasn’t. Not anymore. I was thin and on my way to becoming James Cagney Alejandro handsome.

Our driver hurried to the scene. He pulled at the wife’s hair so that he and Malen were caught in a tug of war, only he was as tiny and weak as the wife was. Soon the whole housekeeping staff, my parents, two older sisters and older brother surrounded the three. “Enough,” my father calmly said. His neck was stiff and his upper lip twitched furiously. Though not as husky as Malen, he stood at equal height with all 5′10″ of her. He looked into her eyes, his own eyes large and commanding. Suddenly, she shrank in stature. She was no longer a part of the staff.

I never said good-bye to Malen. I never saw her again after that. By the time I had come home from school that day, she was gone. A year later I heard from one of the other maids that Malen was back in the province, taking care of her ailing mother. What province she called home, I didn’t know. If she was married, I didn’t ask. James Cagney continued on as the neighborhood watchman, saluting cars that entered and exited the neighborhood gate. Whenever my car would pass, he’d salute at me with a faint smile of recognition. And then one day he was gone, too.

Image courtesy of prod1.agileticketing.net