Thank you for featuring “Writer’s Block/ Queer Authors of Note” as your cover story in the May 16 issue of Frontiers Magazine. I was particularly drawn to the article on poet JC by Mikel Wadewitz. I admire that Mr. C is creating fiction that is moving beyond the commonplace subject of an American-identified Asian discovering his or her parents’ heritage. Although the theme of biculturalism will always be crucial in voicing the lives of many an Asian-American, not all of us Asians in this country relate to it, for not all of us are American born and raised.

However, while I support Mr. C, I am confused as to his reference to the works of Gustave Flaubert and Jane Austen in explaining his use of cultural icons in his writing. Of “Madam Bovary,” Mr. C says, “What does she want to do? She wants to take drugs and go shopping!… It [Flaubert’s novel] was all about trends and fads.”

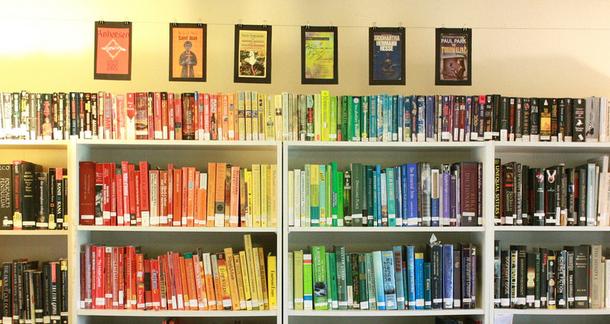

Image courtesy of xingu2.files.wordpress.com

To say that Madame Bovary simply wants to take drugs and to shop is to trivialize Gustave Flaubert’s creation; worse yet, his genius. Her psychopathic extravagance is more deep-rooted than a mere concern to keep up with current trends and fashion. Emma is a woman so clouded by illusions of love and beauty that she is obsessed with living a life possible only to the heroines invented by the serial romances in which she indulges. Nowadays, a small-town girl who fancies great extravagance has Cannes and Hollywood to flee to or a presidential aspirant of a third-world country to seduce. Emma has the misfortune of having been born at the wrong time (19th century France), in the wrong place (an obscure province named Les Bertaux), and in the wrong class (the daughter of a shepherd). Her sole recourse of escape from the doldrums of her everyday existence is the hapless doctor who mends her father’s broken leg. Onto him, she projects a future of satin ball gowns and velvet divans.

Mr. C is right about one thing: Emma would go mad with all that shopping and those parties, and indeed she does, which is the whole point of the novel. Her inability to cope with the reality of her husband’s limited medical skills and his modest income drives her to the brink of madness. Her romantic aspirations consume and destroy her; she literally shops till she drops. And yet, through all that madness, I cannot find one passage in “Madame Bovary”where Emma gets high on the abusive substances of her day. The only high she ever truly suffers from is a delusion of grandeur that persists 24/7.

Hence, “Madame Bovary” isn’t “all about trends and fads.” It is about the emotional and psychological toll that a fixation on trends and fads can have on an individual because of the idealized lifestyle that such superficial trappings represent. Fashion and furniture are not mere props that Flaubert uses to ground the reader to the setting of his novel, the way Mr. C claims to do so in his own writing. They are Flaubert’s primary means of character development.

Image courtesy of pinimg.com

Mr. C also integrates ‘70s and ‘80s entertainment with his poetry and fiction to “illuminate how seemingly absurd things like pop songs can actually mark a very important and even serious moment in one’s life.” To justify his use of this technique as a long standing literary tradition, Mr. C states, “Look at Jane Austen: [Her characters] kept going to these dances and balls, and it’s like, ‘When did that become literature?’”

Jane Austen depicts in detail the absurdities of parties and of social gatherings among the 19th century British bourgeoisie not so much to manifest their importance of a moment in a character’s life than as to emphasize the absurdities of a very society, way of thinking, and way of living. Ever since “Mansfield Park” and “Persuasion” have claimed their thrones in the annals of world literature, Austen’s novels have been hailed as some of the greatest social satires ever published. As such, they transcend the personal realm of Fanny Price and Anne Elliott to embrace that of humanity at large. Pedigree, economic status, social standing – these are factors that have obsessed every society in every culture through the ages and will remain to do so for ages more so long as avarice is a human folly.

It seems that some of the queer men and women of letters have yet to thoroughly understand their responsibility to the world. Literature is one of our most potent forms of asserting our pride for who we are and for the diversity of experiences that our community encompasses. Once this era of online dating has passed and the last of the Black Parties has short-circuited, our legacy to future generations will be our words. Upon these words, the transgenders, lesbians, gays, and bisexuals of tomorrow shall build their own forum for recognition and acceptance. If today’s queer writers are to speak and to write of the historical correlation between literature and society, then they must do so not at face value, but with great enlightenment.

Image courtesy of litreactor.com