Image courtesy of wordpress.com

An article I read when “The Pianist” (2002) was in theaters explained the increasing volume of Holocaust films in the second millennium. It stated that as survivors of the horrific event age and pass on, it is all the more important to preserve their history in cinema. I have seen quite a few Holocaust films, and it is fascinating that even though they all revolve around one subject, each is different from the other. The most recent is “Woman in Gold” (2015). Perhaps the reason it continues to move me is that I saw it only a couple of weeks ago, so it is fresh in my memory. But I have a feeling it will stay with me for a long time. Helen Mirren is in it, and no film can go wrong with her.

“Woman in Gold” is the true story of Maria Altmann’s redemption for a choice of life over death that has haunted her for 60 years. Altmann (Helen Mirren) is a Los Angeles boutique owner who, with her husband Fritz (Max Irons), fled Nazi-occupied Austria in 1938, leaving behind her family and personal effects, including a Gustav Klimt painting after which the film is titled. It is a portrait of her Aunt Adele (Antje Traue), a woman she looked up to as a second mother. Under Austria’s restitution law of 1990 that examines the Austrian government’s ownership of art works the Nazis pillaged, Altmann seeks the help of lawyer Randol Schoenberg (Ryan Reynolds) to reclaim the portrait. They go to Austria, where they encounter recalcitrant bureaucrats and legal ramifications, all of which make for scenes of courtroom drama in both Vienna and the City of Angels. But the fight against unjust jurisdiction is not what lies at the core of “Woman in Gold.” It is guilt.

Image courtesy of cdn.cnn.com

“I left them here,” Altmann laments of her parents to Schoenberg after the judge rules in her favor. Spectators to the trial are in the courtroom, applauding the verdict. It is unequivocally a victory of reparation for a war crime. However, Altmann chooses not to celebrate. Instead, she looks out a vestibule window at children playing in the garden, remembering perhaps her idyllic childhood in a country to which she had sworn never to return because of a war that sent her parents to perish in a concentration camp. On the day she fled, father (Allan Corduner) and mother (Nina Kunzendorf) bid their last request of their daughter (Tatiana Maslany): live, be happy, and remember them. Robbed of mementos and photographs, journeying on to freedom in possession of nothing more than the clothes on her person, Altmann would abide by their dying wish for the rest of her life. Yet we wonder what nightmares of her parents’ fate must have plagued her as well as what guilt. That it is the natural inclination of a parent to sacrifice one’s own life for a child does not assuage the albatross of remorse on the survivor’s conscience. Neither does reclaiming an object that is a tangible link to the past.

Image courtesy of pinimg.com

And yet, the battle was worth it because even though the dead can never be resurrected, Altmann at long last has among her belongings a thing of beauty in which their spirits will live forever. Hers is a triumph that speaks to us all, for her plight had been that of humanity. We see it today. As we obsess over “The Game of Thrones,” actual beheadings occur in Iraq. 20 years ago, America’s fixation with reality TV coincided with the reciprocated genocide of the Hutu and Tutsi tribes in Rwanda. A decade before that, the novelty of M.T.V. overshadowed the catastrophe that was Lebanon. Yes, we are aware of world events, though as other people’s stories rather than our own. Our personal world revolves around recreational preoccupations.

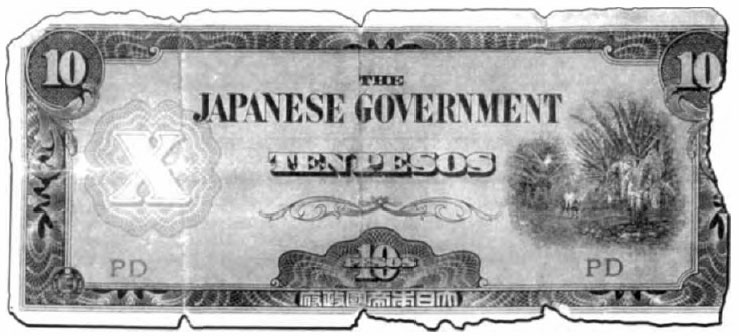

Such was the case when Jewish refugees attempted to escape persecution in Europe on the brink of World War II. The United Kingdom and the United States turned them away, sending them back to their places of origin where they would meet their doom. Meanwhile, those who didn’t know any better danced the swing to the music of Benny Goodman. One country did open its ports to the Jews – the Philippines. From 1937 to 1941, President Manuel Quezon collaborated with a group of Jewish-American businessmen residing in Manila to transport 1,200 Jews from Europe to the Philippines. A compound for the émigrés underwent construction in Mindanao, where they would have thrived and contributed to the community as they had in their original homelands. The plan was to welcome 10,000 Jews, but then Pearl Harbor thwarted Quezon’s vision. 24 hours after the Hawaiian military base was attacked, the Japanese Imperial Army marched into Manila, putting the Philippines at war with Germany’s ally in the Far East.

Although World War II was 25 years before I was born, it is a part of my history by virtue of my parents. My father was 11 and my mother was five when the war in the Pacific erupted. My father once told me that he had thought the bomb blasts he saw from his window illuminating the night sky over Manila were fireworks. Four years later, he would be squatting in a building when the Imperial forces, in the fury of defeat, systematically raped women, then bayoneted every Filipino in the capital. My mother has accounts of the Japanese seizing the grand house she lived in as their headquarters and of a Japanese general’s harboring such a fondness for her that the general would take her on rides astride his horse. Both parents lost their homes in the end. They were burned to the ground. It’s the same story with every war. World leaders express hostilities, but it’s the blood of the citizens that redden the land. Those who survive to tell the tale speak of rebuilding life from nothing, like castaways of a shipwreck.

Image courtesy of bibliotecapleyades.net

Now if we still haven’t empathized with such disgrace, consider the calamities of nature in our own backyard. Autumn in the East Coast isn’t what it used to be 30 years ago. When I moved to Boston for college from the Philippines, it may have been cold with some rainy days, but never did a storm occur of biblical proportions. Then in 2012, Hurricane Sandy flooded Manhattan, damaging even the most upscale of properties and smashing automobiles against edifice walls with the ease it would have a piece of lumber. When Sandy passed, the brutality of winter left cars stranded on highways and generated reports of people freezing to death. Let’s not forget Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans seven years earlier that resulted in a fatality count of close to 2,000 and scores of homeless. News footage of shoes, picture frames, and table lamps strewn across a landscape of flattened houses conjured the horror of a war zone. No doubt sacrifices had been made in which individuals had to choose between saving themselves and saving their loved ones.

This brings me back full circle to “Woman in Gold”: live, be happy, and remember. We can have our home and family torn away from us at any moment. We can be forced to make a choice between life and death that we could regret for the rest of our lives. As a San Franciscan, I live with the threat of loss every day. An earthquake could strike this instant. If the earth were to devour everything I own, then all I would truly have left are remembrances. However, remembrances would not be enough. As mortals, we are subject in time to the frailties of the human condition so that inevitably our memory will fail us. Hence, while we are able, we strive to retain all that is sacred in our hearts through the poetry of words and the light of cinema. Once in a while, we gain immortality through brush strokes so divine that they create a national treasure priced at $100 million. Although none of this may ease the pain of a parting, they’re the best we can do to honor lives sacrificed.

Image courtesy of 2.bp.blogspot.com

I enjoyed your review of Woman In Gold. I saw the film 2 weeks ago and was

moved by Altmann’s pursuit of justice. The Austrian activist who assisted her is a German actor who previously appeared in an independent film featuring pre-Occupy activists. Thanks for informing us of Manila’s role in attempting to estsblish asafe haven for Jewish refugees.