Image courtesy of highlandernews.org

On my 25th high school reunion with the International School Manila (ISM), I ran into a guy who used to bully me. (http://www.rafsy.com/films-1960s-1990s/big-the-best-that-we-can-be/) The moment was not only nerve wrecking but also unexpected. Robert had left after middle school and was at the reunion by invitation from an alumnus with whom he had kept in touch over the decades. Until then, I would occasionally wonder what ever had happened to Robert. He had been orangutan portly with dark hair and beady eyes, and I envisioned him in adulthood as an obese lout, surviving on a diet of beer and McDonald’s, his home in America a cigarette cesspool of a trailer car.

A man the complete opposite stood before me. Robert was Mr. Clean incarnate – bald, brawny, and sporting a collarless white tee. He approached me at the poolside buffet to compliment me on my own musculature and then, “I don’t recognize you. I recognize almost everybody here but you.” I responded that I remembered him very well, referencing his heavy weight when we had been kids as proof, though I dared not mention the homophobic epithets he would hurl at me. As the sensation of worms churning in my insides debilitated me as if I were once again 11 years old, Robert expressed pride in the trajectory his life had taken since leaving ISM. Karate put him in shape, and a job first as a policeman followed by one as a juvenile correctional officer enabled him to release his aggression on the right side of the law. “So you beat up guys,” I said. “I’ve been known to do that,” he said with a laugh. (http://www.rafsy.com/films-1960s-1990s/big-the-best-that-we-can-be/)

Image courtesy of dnaindia.com

Some past traumas stay with us through adulthood, and bullying is one of them. (http://www.rafsy.com/films-1960s-1990s/carrie-it-gets-better/) The trick is how to put it behind us. The It Gets Better Project was founded in 2011 in response to the reports in recent years of verbal and physical assaults directed at gay, lesbian, and transgender youths. Its website (www.itgetsbetter.org) offers video clips of former victims who have prospered as adults; in effect, relaying the message that the torment endured in childhood and adolescence should not cause one to languish but to strengthen, for the future is about rebirth. Finally, we are taking an aggressive stand against an issue too long ignored. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, as of 2015, the number of suicides among youths between the ages of ten and 24 amounts to 4,400 a year, with bullying a primary impetus. (http://www.heyugly.org/aboutStatistics.php) Due to the disturbing statistic, cinema itself is bringing attention to this social ill.

Image courtesy of pinimg.com

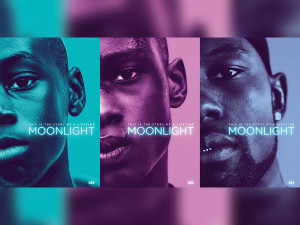

One such film is “Moonlight” (2016). A coming-of-age, coming out tale, it follows a boy’s life as he braves face beatings in school and name callings at home. We are introduced to Chiron when he is just about ten years old, nicknamed Little for his timid personality. Little (Alex Hibbert) is fleeing from a pack of neighborhood no-gooders when he gets cornered in an abandoned motel. There he meets Juan (Mahershala Ali), who comes to his rescue and ultimately becomes the boy’s surrogate father. The bullying worsens in Chiron’s teens, though sexual identity is of no provocation. Lanky in oversized clothes and with head bowed as if in constant remorse, a young Chiron (Ashton Sanders) is prime target, a cat in a lion’s den. High school sucks, and home is no haven when mom is a junky who digs into her son’s pockets for cash to fund her next rush.

As an adult, Chiron (Trevante Rhodes) travels far for a fresh start. He drops the name Chiron for Black and, with a new identity, develops his physique into a steamroller of muscles, brandishing jewelry and gold teeth. No one dares mess with a hulky Black. However, the stony exterior belies the tumult within. Too much has happened to Chiron for him to simply let go, until he reconnects with childhood buddy, Kevin (André Holland), and onward he treads on a path to love and forgiveness.

Sexual awakening is petrifying to the young. It spurs a sensation never before felt, a mystery we boys seek the answers to in men’s magazines found hidden in our fathers’ closets. For those of us who experience lust for one of our own gender, there is no answer, and thus we fumble through the maze to a destination of discovery. So it is for Chiron. Evenings for him have a sensuous aura. The tide is high. The moon is a crystal ball of electricity. One night he has a wet dream. A 16-year-old Kevin (Jharrel Jerome) is smiling a smile part mischievous, part inviting. He is fornicating with a girl in some outdoor space at the end of a labyrinthine passageway: a terrace, maybe, or an alley. Chiron watches from a doorway, drowning in a cauldron of terror and desire. The smile is directed at him.

Image courtesy of wordpress.com

We all experience a Kevin of sorts. Mine was in the body of Guy, another boy who picked on me in the sixth grade. While I detested Robert, my feelings for Guy were contradictory. He had dark hair cut in the signature 1970s fashion of feather bangs, freckles, and that slightly bow-legged jock strut. Robert, he, and I were in the same gym class. One day in the locker room, Robert, seated on a bench, pulled a prank on Guy by attempting to yank his briefs from his ankle so that he was hopping on one foot, laughing like a goofball as his penis flopped. The vision of Guy naked was one I would have for the rest of my prepubescence on many nights that I lay in bed. He may have been a jackass, but I didn’t hate him.

Guy also didn’t proceed onto high school at ISM. Nobody I know of had maintained contact with him either. What man he became is hard to tell, for even bullies can undergo changes that vitalize in them a latent kindness. Here’s a case study courtesy of my brother-in-law. The quarterback to his Long Island high school would threaten to beat up other boys if they refused to do his homework. According to Steve, “He had to repeat a grade twice. That’s how dumb he was.” The footballer was aged 16 in a class of 14-year-olds. Fast forward 45 years later. He is now a science teacher in that same Long Island high school. Student comments Steve has googled are awash with commendations on his friendly disposition. “He’s such a nice guy,” they chime.

At the 25th class reunion, Robert took the initiative to reintroduce himself to everyone, exerting the extra measure to compliment married men for having beautiful wives. Two years later, I learned on Facebook that Robert died of a heart attack. I wouldn’t call his passing retribution. I’d call it irony. He seemed to be making amends for past reprehensible behaviors. Then fate dealt a blow. I was rather surprised at my sadness when reading the news, for I carried no grudge towards Robert, never had. Neither did I care for an apology during our brief interaction as grown men. A state of dither aside, I had allowed bygones to be bygones a long time before. Cutting loose enabled me to thrive through the decades so that I embraced my sexual identity in college and, shortly thereafter, came out in San Francisco.

Image courtesy of giphy.com

This spirit of strength in letting go suffuses “Moonlight” like a haunting melody. In certain African mythology, the moon is the goddess of creation, a symbol of motherhood and fertility. Its light promises the birth of a new dawn, and as the sun rises, we see more clearly where tomorrow is meant to take us.