Image courtesy of fontmeme.com

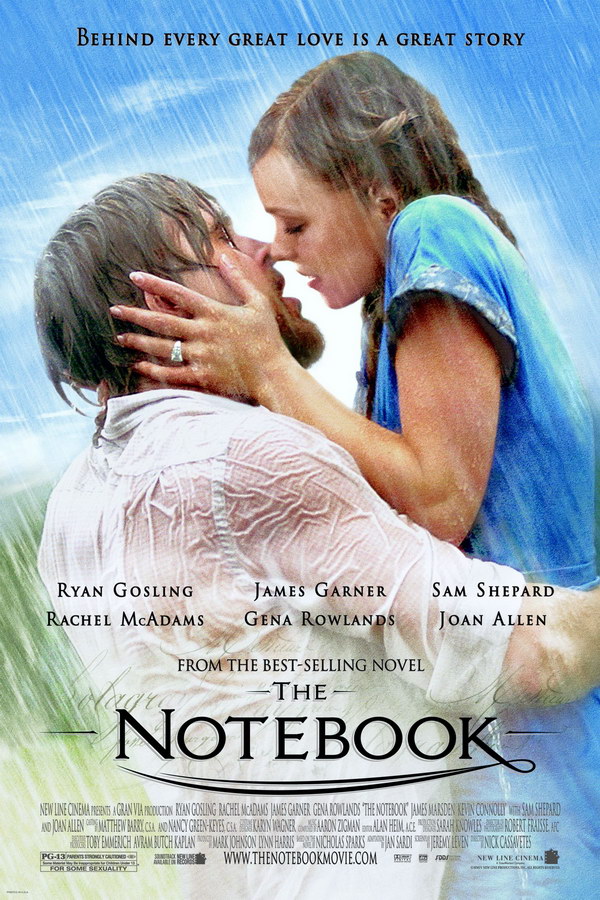

Sure, “The Notebook” (2004) is sappy, a weepie contrived to appeal to a demographic of teen girls and ladies with lacquered nails. But hey, the film has a male fan base, too. 12 years after its release, “The Notebook” is now a classic, primarily due to Facebook. Originally ignored when released in theaters, it created a buzz when postings of the love story that vanquishes Alzheimer’s crowded the social media.

From the very beginning, “The Notebook” gets it right by introducing us to Allie (Gena Rowlands) and Duke (James Garner) in their old age. She is in a nursing home. He is a frequent visitor whose identity causes her much confusion. We sense the two must have a history for Duke to be diligent in his visits. How sprawling and beautiful that history is only becomes apparent to us when Duke reads passages Allie had written in a notebook. As expected, they were once a vivacious pair in the throes of a passion that glosses the world an eternal spring. And so we watch the progression from youth to agedness. Such is the power of the flashback, its ability to contrast with starkness two polar points in life: birth and death.

Upon love’s nativity, young Allie (Rachel McAdams) is a rich girl and young Duke (Ryan Gosling) is a poor boy torn apart by a class structure that deems them unfit to wed. However, she isn’t distraught for long. Enter Lon Hammond, Jr. (James Marsden). Her societal match, Lon is a Southern aristocrat with a penchant for wine and horses and a genuinely nice guy, besides. Since he has the approval of Allie’s parents, Allie experiences a resurgence of joy, and with her faith in love restored, she believes she is over Duke. She isn’t, of course; this is meant to be a tale of a woman torn between two lovers. Hence, the guy comes back and what we’ve got is drama upon drama.

Image courtesy of copyblogger.com

Really, “The Notebook” is all very formulaic. Nonetheless, the movie resonates with us because we all eventually fall prey to time and the loss of memory. As I approach the end of my fifth decade, the notion of a mid-life crisis flabbergasts me. When we are young, we think we will be young always, all the more in the midst of childhood. As long ago as that was for me, I still feel the security the white carpet and four walls of my parents’ room assured me, in a white house on a street named Carissa. With “The Carol Burnett Show” my family’s favorite TV viewing, laughter filled the room. Not even murder could dampen the conviviality of our evenings, thanks in part to “Ellery Queen,” the whodunit detective series, every episode of which introduced a victim about to be offed talking to the camera as if the viewer were the killer. Such a gimmick engaged us in a guessing game for the next 30 minutes.

My reality paralleled the ebullience of the alternate universe encased in a black and white portable TV: the birthday cake Tita Zennie baked that was a diorama of match box cars on an icing highway; sleep-overs with my three favorite cousins Richard, Ariel, and Joel; sun blazed weekends as we lounged by the pool, the grass and shrubs that surrounded us the brilliance of polished jade. An accident on the day I turned eight nearly ruptured this idyll existence. My parents had given me a clock, one that with its white stem and red head resembled a flower. At school, I was excited for dismissal so that I could return home to gaze at the glow in the dark numbers as the time piece ticked away the seconds. I ended up at the dentist instead.

Image courtesy of dentistryatthecrossing.com

During recess, in a game of patintero, where players were dared to cross a line without being tagged by the It who stood on the demarcation, I had not been looking in front of me while running to avoid the It. In a moment as spasmodic as the shower scene in “Psycho” (1960), life was reduced to a series of splice edits. A boy before me was crying; my teeth had formed an indentation on his bald head. I turned to the side, only to witness my friends recoil in horror. I looked down. My white shirt was red. I attempted to shut my mouth but couldn’t. One incisor was protruding from the gums, while the other had fallen out. For I was numb from shock, an older boy brought me to the clinic, where my mother was then contacted. At home, as I rushed to the bathroom to change out of my bloodied top, I glimpsed my clock and thought of the mishap, This is a gift from the devil.

The dentist reinserted the incisors, a procedure that required five anesthesia shots and took three hours. This was 1975. Needles then were tooth pick thick. I had pleaded with Dr. Eraña to wait until I dozed off before the operation commenced. Caressing my hand, she would ask, “Are you asleep now?” I’d shake my head, until she finally said, “We need to get started.” I can still hear the crunch upon contact between the needle and the gums – the snack, crackle, pop of Rice Krispies. “You’re the bravest boy in the world,” Dr. Eraña said when the operation was done. She was impressed that I didn’t cry, contrasting me to a grown man whom she claimed had been sobbing the other day over work done with his molars.

Image courtesy of www.talltreesalaska.com

So I survived, and my childhood resumed its innocence. We moved to a larger house on a street named Acacia, with a larger pool in a larger garden. Trees were ever present during my formative phase. Just as leaves sprout on branches, layer upon layer of foliage that reach the sky, so did one gleeful memory after another. It seemed they would never end. Every weekend was a frolic in the pool. Every summer brought me to relatives who reside in America. Every Christmas and New Year’s gathered yet more of the extended family in our garden, a landscape of hillocks and orchids and trees a bonanza of tropical fruits.

Love renders our memories golden. To an equal degree that Allie and Duke in “The Notebook” regard each other, we treasure those who have been a part of events we have come to enshrine in our thoughts. Yes, we all have stories of romance to narrate, perhaps not on the scale of a Nicholas Sparks heart tickler, but some even so that honor our dedication to a place and a person… be it a lover, a friend, or a relation. We are the sum of our memories. To lose them would be to lose who we are. Thus, our ceaseless efforts to keep them. We take pictures. We maintain personal bonds. We write.

Image courtesy of pinimg.com

Our efforts adapt an urgency as time hastens. Funeral bells toll. Voices diminish into a murmur. Faces fade. Do not forget. Do not forget. Without the love remembrances sow in us, we are vacant entities, bodies bereft of a soul.