Image courtesy of amazonaws.com

My mother asked me when I was 12 who my hero was. The question might have been in conjunction with a school paper I was assigned to write. I didn’t have an answer. “Daddy,” she said. I laughed. A hero to me was a dead guy whose mug appeared on money, a general or president or civil rights proponent on the scale of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi. Then again, this was 1979. Whatever acts of valor on the part of the commoner, journalism tended to bury beneath political sensationalism. The despotism of Cambodia’s Pol Pot may have united the globe in approbation, but torture tactics of yanking nails from fingers and the force feeding of human feces produced more hard copy than the refuge a farmer might have provided a government dissenter, and while American bureaucrats that Muslim extremists had taken hostage in Iran received laurels upon their homecoming, we saw their plight as unique to a region too far to pose as a threat to us.

Image courtesy of squarespace.com

The world hasn’t been the same since 9/11. Nowadays, we are more probable to credit with the honor of hero citizens of our community who every day disappear into the throng of pedestrians and commuters off to a nine to five existence. Although we’ve always known that firemen risk their lives, we never witnessed until that day to what extent they hold hallowed their oath to put our well-being ahead of their own. We’re worth that much. In the years after, friends and neighbors have risen above the crowd to champion humanity. Kenyan Peter Kithene suffered the death of siblings and parents by the age of 12 due to a lack of medical aid, a loss that propelled him to establish healthcare in Africa’s remotest territories. Maiti Nepal in Kathmandu serves as a rehabilitation center for female victims of sex trafficking, thanks to the leadership of Anuradha Koirala. In the Philippines, Efren Peñaflorida brings education to street urchins via a portable library and blackboard.

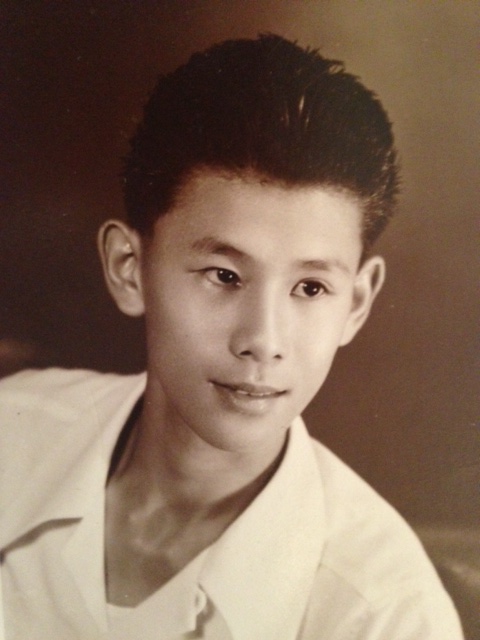

Heroes all, and all are a paragon of the heroism implicit in us. We don’t need to put our mortality on a grill to save others. That we are exponents of life is credential enough. This my father is, he whose origins were mired in hardship, which could be why my mother mentioned him. My father lost his own father at the age kids learn the alphabet. To subsidize in the family income, he relinquished childhood to work as an aid to fishermen, accompanying his mother at the end of the day to collect leftovers from neighbors so that, along with his five siblings, they could have a meal. At 11, he left Cavite, this city by the sea where Spanish galleons once docked, for the promise of the capital, where in the ghettos he earned his keeps as a cigarette and newspaper vendor:

Image courtesy of blogspot.com

A hundred years ago, Tondo had been the center for blacksmiths and booksellers, carpenters and nose and ear cleaners, a thriving center at a time when people were few and trees were plentiful. Now it was a garbage dump. White papers and papers the color of the rainbow – torn from notebooks, shredded, ripped off walls – paved empty lots, creating a floor mosaic of scrambled letters in every font and size. Windows to houses of wood and corrugated steel piled on top of the other like layers of mountain caves. In this canal, muddy waters buoyed plastic cups, and in that, streaks the brownish green of a serpent slithered to the horizon.

This is Tondo in the 1980s, partially the setting for a novel I’ve entitled “Maria Celeste,” about a provincial girl who migrates to Manila during the Marcos era to pursue her ambition of becoming a singer. My father’s Tondo was 40 years before that. Even then, he said, the living conditions were squalid. My father had been under the guardianship of a family friend. He called her Ate Lunti, ate being the respectful epithet for big sister. I met Ate Lunti when I was a child. So deep was his gratitude to her that he would make it a point to take my brother, sister, and me on visits so that she could see how well he had turned out, both as a family and a career man, he an ascending banker whom newspapers and magazines profiled. Ate Lunti had white hair and was so wide on the hips that she was immobile. I have no memory of her in motion. I see her in a moo moo dress, sitting on a bed covered with white sheets turned gray from age, the walls around her weathered wood. I see hints of sunlight, but no window. If there had been one, drapes could have covered it to serve as a screen from the heat. I see a smile. That’s how proud she was. My father’s story is so inspirational that it’s the stuff of movies. Watch “Ratatouille” (2007) and you’ll see what I mean.

I know what you’re thinking. “Ratatouille” is a cartoon, a somewhat gelastic one at that. Remy the rat befriends Alfredo Linguini, a clown of a bumpkin wiry with red hair as curly as cauliflower and who works as a garbage boy in an upscale Parisian restaurant. Alfredo is no ordinary floor mopper. The boy has the makings of excellence. He finally gets his chance to shine when he recreates a pot of soup that had spilled to the floor. The diners savor it, and a collaboration between rodent and human begins. By hiding underneath Alfredo’s toque blanche, the rat helps the boy rise to the status of a culinary master as it gives directions with a pull of the hair on what ingredients to use and when to stir. Remy and Alfredo are such a team that they sway over Paris’s most revered critic. Indeed, what praise flows from Anton Ego’s pen: Not everyone can become a great artist, but a great artist can come from anywhere.

I know what you’re thinking. “Ratatouille” is a cartoon, a somewhat gelastic one at that. Remy the rat befriends Alfredo Linguini, a clown of a bumpkin wiry with red hair as curly as cauliflower and who works as a garbage boy in an upscale Parisian restaurant. Alfredo is no ordinary floor mopper. The boy has the makings of excellence. He finally gets his chance to shine when he recreates a pot of soup that had spilled to the floor. The diners savor it, and a collaboration between rodent and human begins. By hiding underneath Alfredo’s toque blanche, the rat helps the boy rise to the status of a culinary master as it gives directions with a pull of the hair on what ingredients to use and when to stir. Remy and Alfredo are such a team that they sway over Paris’s most revered critic. Indeed, what praise flows from Anton Ego’s pen: Not everyone can become a great artist, but a great artist can come from anywhere.

My father once told me that he was never a star student nor had money ever been an obsession. When, in the fifth grade, I came home with five C’s in my report card, my mother blew her top while my father, his voice calm, said, “I was never good in school, but I tried.” His message: it’s unfair to demand perfection; what’s crucial is that one strive to be the best that one can be, and if the best is a C, then so be it. Past grades had indicated that I was capable of more. Though I’ve never been a straight A student, I’ve always been pleased of what I was able to achieve because I had applied myself. With his knack for numbers, my father had gotten himself out of the streets. No goal to him was impossible, and with the incentive to be the father he never had, he set those goals as a must, his accomplishments an example to all that prosperity can flourish from poverty in the same way that artists and heroes are born in any situation.

Image courtesy of pinimg.com

And so I write:

Even on cloudy days, Celeste saw brightness. On the stage, she could will Cherry to appear however she wanted and, with her music, claim the place as her own. She learned everyone’s name. She regarded her audience as sharing the same home as she, not under one roof but under one sky. Ermita was where loops of jeepney antennas and hearts painted on buses whizzed around them amid screeches and honks and cusses. Hubcaps shapeless as kneaded dough and trash barrels littered pavements. A movie billboard depicted Nora Aunor, Dolph Lundgren, and Eddie Murphy with lopsided noses and fleshy fingers painted in pinkish swirls.

With the God-ordained gift of a voice, my novel’s heroine earns the adoration of working class folk and social outcasts, all who gather in the city’s tourist belt of brothels and karaoke bars. Her own heroine is Nora Aunor, whose grand slam at a singing competition during the Woodstock era lifted her from the sewers into the consciousness of every small town girl. Fighting tales are a part of our collective identity. We need winners. They give us something to aspire to, someone on whom we can project much of what we wish to be – a hero – and they encompass every spectrum of humankind, from a kitchen hand named after a noodle to the men whose surnames we bear as our legacy.

Image courtesy of livingfreenyc.com

Interesting and thoughtful article. Please read the note I left on facebook about SF Symphony tonight?

Richard from the movies group . . .