Image courtesy of img.moviepostershop.com

It’s an unlikely friendship. Ratso (Dustin Hoffman) is a thief and a conman. Joe Buck (John Voight) is a Texan cowboy fresh off the bus in New York City. One could have been born with hair already greased and teeth rotten. The other is an innocent under the mirage that Upper East Side matrons are generous with their cash for a Southern drawl and a gum-chomping grin. They meet at a bar after Joe experiences his first brush with disenchantment: rather than paying him, a lady who picks him up – she the perfect client with bleached do, leathery tan, and poodle on a leash – breaks into tears, humiliated that he should ask for monetary compensation, and out of pity Joe ends up paying her. Ratso advises the novice to get a pimp, but it will come with a price. So Joe empties his wallet, only for Ratso to lead him to a preacher – a groveling sort bald and fat in a crimson silk robe, more the image of a lecher than an evangelist. The pulpiteer forces Joe to his knees in prayer before a make-shift altar of the Virgin Mary fixed onto a closet door. A good laugh Ratso has, that is until Joe motions to punch the finagler. What holds Joe back is Ratso’s plea that he’s a cripple. Plus, he’s got space to spare in a rat hole of an abode. From fall to spring, the two live together amid broken windows and a rinky-dink gas burner. Not only does Ratso become Joe’s meal ticket and mentor on petty crime, but he is also as much a dreamer as Joe, our stud whose “Midnight Cowboy” (1969) act works, according to Ratso, exclusively on “fags of a certain type.”

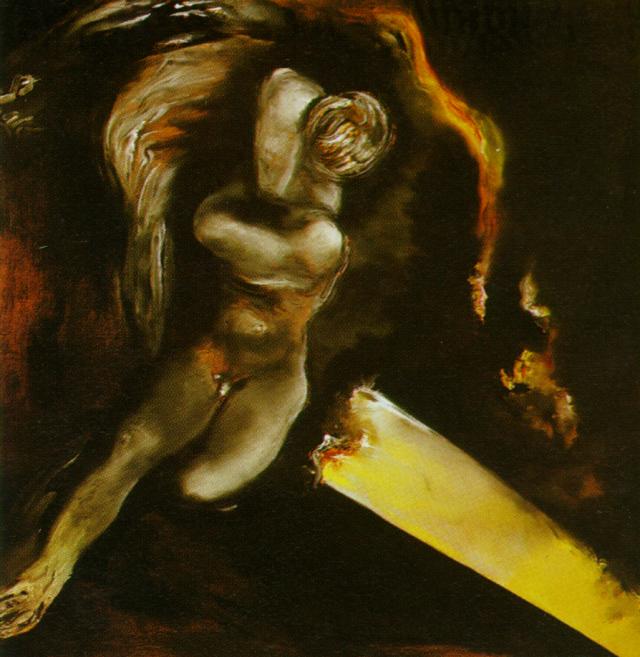

Image courtesy of wikiart.org

Precisely what feelings Ratso develops for Joe is ambiguous, though one thing is clear – his protégé is more to him than a hustler on the make. Ratso’s paradise is Miami, where he envisions himself dressed in white, surrounded by ladies in bikinis and outrunning Joe on the beach. Yes, Joe is with him in every daydream, waking hour, and nocturnal slumber. Joe needs him just as much. Ratso turns out to be the only soulful fellow in this city of people who touch but never connect, for how lonely indeed are the men who hook up with Joe. A college student, a middle-aged traveling salesman… they both say they’ve got cash, but fail to deliver. What they truly need is love, or the illusion of it, and intimacy as a business transaction plays no part in the illusion.

So many hungry souls populate the world. On certain nights, as we lie in bed while the roar of a car engine outside our window grows ever more faint in the distance, the stillness that surrounds us can invoke all sorts of thoughts. Loneliness is a condition we all share. It’s the basis of many stories, “Midnight Cowboy” being one so poignant that it was awarded the Oscar for Best Picture. This brings to mind another tale, one more blatant in its gay theme, David Leavitt’s novella “Saturn Street.” Jerry, a non-profit volunteer, delivers food to AIDS sufferers, and a person consigned to his tending is a man named Phil Featherstone, a former porn star. Jerry never expected this, that a proverbial Greek God, the subject of many of his sexual fantasies, should appear before him alone in a dilapidated apartment: drab furniture, dirty beige carpeting, walls stuccoed as if they’d been slathered with cake frosting. The dwelling might as well be a morgue. In the progression of Phil’s illness, his emaciation and loss of vision, Jerry becomes the lone person Phil counts on for survival. The caregiver provides Phil not only lunch, but also conversation, a human presence, love and friendship.

Image courtesy of highlandecho.com

We never see the beautiful as desolate and prone to illness. They can have anybody they want. A porn star in particular must have it all, he who is filmed for posterity copulating with guys equally as desirable, while we plain folks are resigned to our lot of wanting; hence, Joe Buck. Some of us want so desperately that we fall to our knees and clasp our hands in supplication. Nobody wants to be in the position to beg. It isn’t respectable. It’s pathetic. “Don’t beg,” I once told someone, “not for anybody, not for me. Nobody is worth it.” He was a heavyset man at a bathhouse in New York, celebrating his birthday. I happened to pass his room when he stopped me. He wasn’t obese in the vein of a sumo wrestler. He was more Kevin James, whom I think is adorable in his clean-cut persona and physical pratfalls. Stoutness notwithstanding, James has got charisma. The dude is sexy. James may be self-deprecating, but never self-derogating. “Please,” the man kept saying. And then, “I’m begging you.”

I meant it when I told the man that I wasn’t worth the begging. I had my own issues of self-image – a scar on my chest, bird legs, a slight physique. Perhaps these flaws existed largely in my head; nevertheless, they existed. We all have our down moments. A situation where we are butt naked for all to appraise our worth based solely on the superficial places us in a vulnerable spot. Although looks aren’t everything, they sure play a large factor in a world that’s visual. Our face and our walk are what of ourselves people first lay eyes upon, and thus on which they form an opinion. That is why we are sensitive about our weight and age and our self-perceived “bad angle,” as movie personalities gripe. (Candid shots of stars without make-up are always a devious delight.)

Image courtesy of apa.org

Envy those with the capacity to put precedence to the strength of personality. Had I been one to project an ounce of mettle that those who are internally irresistible do, then I wouldn’t be kicking myself to this day over a missed chance that occurred ten years ago. While at the Powerhouse, a bar in San Francisco that caters to the alpha male prototype of leather bikers and lumberjacks, a guy sat beside me on the pool table. He was frat boy handsome and jock built, so much a catch that the bartenders were quenching his thirst with free drinks. An acquaintance had just gone to the restroom. To start conversation, I used the absent company to channel my attraction for the guy. “My friend thinks you’re cute,” I said. “Well, I think you’re cuter than your friend,” said the frat boy. I had not expected his response. I had not expected anything other than a shrug of the shoulder, a thank you at most. “I don’t know what to say to that,” I said. A moment of awkward silence, then he left. He didn’t leave to go cruising for somebody else at the Powerhouse. He left the bar. It seemed I was the only guy he had been interested in. What might have been? I spent the rest of the evening and many evenings after in a “Midnight Cowboy” funk, as bereft as one of Joe Buck’s johns starved for loving.

As Joe and Ratso are about to enter a party, the former notices how drenched in sweat the latter is with hair unkempt and lips livid. Ratso has been suffering from a chronic cough. We sense this is no passing cold. The guy needs a doctor. Pronto. But Ratso refuses. Besides, they can’t afford one. The most Joe can do is comb Ratso’s hair: “Few dozen cooties won’t kill me, don’t guess.” Ratso is at first peeved by the act, and then, in a moment of spontaneity, he falls onto Joe and hugs him. The moment is a singular gesture of love, the kind that transcends a label, be it romantic or fraternal or sexual. These are two human beings who watch over one another, who are so bonded that every decision one makes from a meal to the next destination on a cross country bus ride involves the other. They’ve come to mean that much to each other.

Image courtesy of wordpress.com

Love can’t be bought. Neither is love begged for. Love just happens.