Image courtesy of saimg-a.akamaihd.net

With love comes sacrifice. The price is worth it when the person for whom we kill a part of ourselves is obligated to us in return. Love is elevated to a higher level… we’ve proven our worth… and promises are enunciated in return that ground in earthly facts the esoteric commitment for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, until death do we part: “I will be by your side even if you become a quadriplegic… I will take care of you if you have a stroke… You can count on me no matter that we lose our home to foreclosure and shack up in a van.” But what if the dear one misjudges our action, the full truth behind our sacrifice too hurtful for the person to bear, so we keep it covert and sustain criticism?

What we have is “The Third Man” (1949). Joseph Cotten is Holly Martins, an American pulp fiction author who goes to Vienna when a childhood friend, Harry Lime (Orseon Welles), offers him a job. Upon his arrival, Martins learns that Lime has died under suspicious circumstances. He stays to investigate, only to discover that Limes is alive as a black marketer, his contraband penicillin stolen from army hospitals and diluted with a substance that causes physical deformities and fatalities. The two have a shoot out in the city’s underground sewage system, a montage of tunnels and shadows against concave walls, but the real fight exists on street level. Martins must deal with the thorny task of regaining the trust of Lime’s girlfriend. The guy has fallen for her.

Image courtesy of popcornreel.com

Anna Schmidt (Alida Valli) is herself guilty of her share of misdemeanors – a false passport, accomplice to Lime’s hiding – but she is ignorant of the vileness of her boyfriend’s business. Lime, as far as she’s concerned, is a dabbler in shady deals of no serious consequence. While she first appreciates Martins for the sincerity of his friendship, a rarity in this Vienna of furtive glances and stalkers who lurk in corners, she later considers him a traitor. Martins has cooperated with the authorities to apprehend Lime in exchange for the nullification of her deportation to the Soviet sector of the city. She gets a safety passage to the West instead. Unbeknownst to Schmidt is that Martins does this only when the extent of Lime’s crimes are disclosed to him.

“Look at yourself,” Schmidt tells Martins at the train station. “They have names for faces like that.” He has answered her question as to why the police are granting her the favor of freedom. Disappointed, she furthermore berates Martins his appellation of Holly. “What kind of name is that for a man?” Such is her loyalty to Lime and her anger at Martins. Martins could have aired all of Lime’s dirty laundry, but that would not have been a decent method to earn Schmidt’s affection. It’s a sticky situation, being glued to someone who wants no attachment to us, watching one’s resentment for us intensify as the person he or she clutches to the heart is the actual villain. Even had Martins bared Lime’s dealings, Schmidt would not necessarily have wept on our hero’s shoulder, her tears an invitation to the condolement of a kiss.

Image courtesy of staticflickr.com

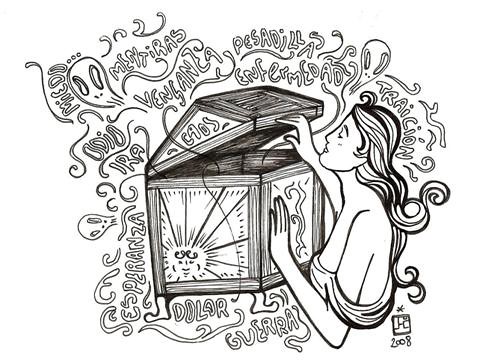

Some things are better left unsaid. Silence spares a person pain. We can write what is too much of a burden to keep buried within, and only to ourselves, though even this is dangerous, for a diary is a Pandora’s box. In it we unload sinful thoughts and seraphic fancies, the seismic tremors of the soul from hatred to a forbidden love. When opened, all that springs forth from its pages cannot be recanted. Martins, for Schmidt’s sake, is a book bound in lock and key.

Life is replete with moments where we run the risk of secrets exposed. “Don’t worry, she didn’t read much,” my sister told me the night I came out. We were walking up Powell Street, headed home from a day of Thanksgiving shopping in Union Square, San Francisco’s downtown, where an 83-foot Christmas tree and a colossal menorah, one across from the other amid an enclave of buildings, both illuminated the night, the former with light bulbs encased in balls and the latter in glass flames. Cable car bells rang as wheels rumbled on tracks, and pine wreaths decked display windows. That was how my mother found out I’m gay. While visiting from the Philippines, she read my journal, which I had left on the dining table, and in it I had written of excursions to video arcades, the only venue then where I could express my sexual identity.

Image courtesy of filmfilicos.com

I had a secret. My mother had a secret. Since she couldn’t contain mine, she called my father in Manila, who then instructed my sister in Los Angeles to inform me on her holiday trip to the Bay Area that they now know of me. Although the revelation saved me the anxiety of sitting my parents down for a formal coming out moment, my journal remained a hushed matter. My sister was merely meant to tell me that I need not hide anymore, not that my mother had glimpsed my inner workings – insecurities and desires and all. My parents still believe I am in the dark about this. So be it. That was 25 years ago, and what my mother had read rocked her nerves. Aside from an epidemic linked to gay men, she and my father had lost something, and of this loss I justified its gravity to friends when they deplored the difficulty a buddy of theirs was experiencing with his own parents upon his coming out.

“In the four seconds it takes to say, ‘Mom, Dad, I’m gay,’ the dreams your parents have been harboring for you all the years of your life are shattered,” I said. They couldn’t comprehend why the blow to Gable’s parents (yes, Gable, named after Clark) since the parents had accepted the homosexuality of a family friend whom they considered “like a son.” My contention was that embraced as this person was, his position was not the same as that of a biological child. From the minute of our birth, our mothers and fathers foresee in us a future opulent with the sort of happiness they had experienced, all of which culminates in our first cry. Courtship, marriage, and parenthood… love’s rituals that every generation celebrates were denied gay men in the 1990s. Gable’s folks were suddenly confronted with a tomorrow that was murky, as the present was licentiousness and death, and history was police raids of public bathrooms with men dragged in hand cuffs to paddy wagons, their names in the following day’s newspapers that listed them as sexual deviants.

My parents never told me what I had taken away from them by coming out. “I thought you were going to marry a Miss Universe,” my father joked when he flew in from Manila, while my mother urged that I be careful. That was all. I’m certain the worry and fear in Gable’s parents weighed on my parents, too, but of what else more, I will never know. In their silence, my mother and father permitted me the freedom to live as I am. I am fortunate to know this. I wish Anna Schmidt in “The Third Man” would give Holly Martins the privilege of acknowledging the degree to which he lays out his neck for her. Maybe, in another story, she will read in tomorrow’s papers the slime bucket Harry Lime was, and our quiet hero will at last get the prize that is duly his.

Image courtesy of media.tumblr.com