Image courtesy of celestialgrace.org

Every family that has suffered the loss of a child has a guardian angel in the dead offspring. This my own family has decreed by virtue of our Catholic faith. I first heard of the belief when my aunt lost a daughter, a stillbirth, nearly 40 years ago. Tita Zennie had three boys. The eldest then was 14 and the youngest was my age, ten. She had longed for a girl and got one. My aunt named her Cherry. On All Saints Day, we stood in the cemetery of the town my uncle, husband to my aunt and brother to my mother, had grown up in. Cavinti is perched on a hill. Stone and wood houses line streets part paved, part gravel. In the square, a church centuries old constructed of volcanic rock overlooks a basketball court, across from which crucifixes and tombstones stand on a knoll a patchwork of grass and earth. Tita Zennie laid a hand on Cherry’s resting place, bowed her head, and sobbed. “Tama na, Mommy,” her youngest, Joel, said. The girl had been born a few months before, and such was my aunt’s grief that my cousin implored my aunt to stop mourning, for she had shed enough tears. Other relatives consoled her with the assurance that, from then on, her family would have an angel by it’s side.

It dawned on me then that my family might have not one guardian angel, but two. My mother’s first pregnancy had been ectopic, while the second produced a boy strangled by its umbilical cord. He was named Philip, and he is buried in the same plot as Cherry. As a child, I heard my mother’s cousin describe him as handsome with soft curls and fair skin. My father had foreshadowed his death. The night before the birth, my father dreamed that a doctor was bundling a baby’s corpse in a newspaper, and the next day, as my father entered the operating room, he saw exactly that. He demanded the doctor to stop so that he could search the hospital for a clean towel; his son deserved a dignified wrapping, no matter that the infant had never breathed life.

Image courtesy of imagekind.com

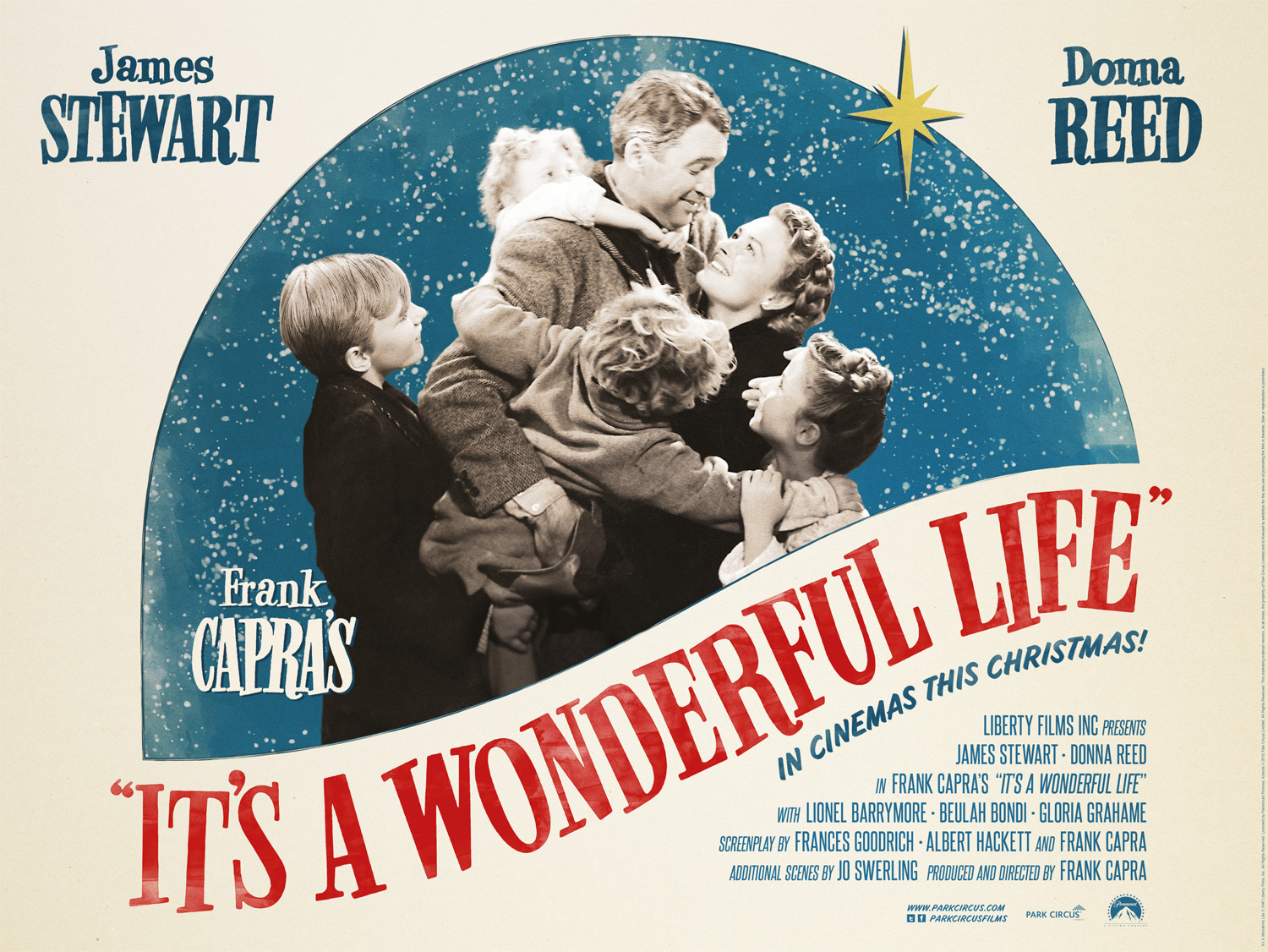

Christianity and popular culture have angels existing in other guises. Gabriel had no relation to Mary, yet God had designated him as the envoy to bear the tiding of her pregnancy, and in “It’s a Wonderful Life” (1946), a Kris Kringle mirthful old man named Clarence (Henry Travers) descends to earth on Christmas Eve in order to earn his wings by means of saving George Bailey (James Stewart), a good Samaritan about to end his life due to a financial crunch that could throw him jail. As George readies to jump off a bridge to freezing waters below, Clarence dives in, yelling for help so that George rescues him. The angel reveals his identity, in whom George confides that he wishes he had never been born. Clarence gives George the rarest of gifts, a chance to glimpse Bedford Falls, New York and those dear to him should his wish be granted.

Image courtesy of nyt.com

Bedford Falls transforms from a community of friendly neighbors and policemen to a pit of depravity populated by goons and gamblers, brothels and saloons, all under the control of Mr. Henry Potter (Lionel Barrymore), the meanest and richest man in town. Only George, through a business inherited from his father (Samuel S. Hinds) that provides affordable housing, would have had both the ideals and the grit to challenge Mr. Potter. Without George, people are on the streets or in slums. The world beyond has changed, too. His brother, Harry (Todd Karns), doesn’t live to adulthood to be the war hero that he would have grown up to be, for George isn’t present in their childhood to save him as he falls into a lake through a crack in the winter ice, and without Harry, comrades in arms whom Harry would have protected also die. “Strange, isn’t it?” says Clarence. “Each man’s life touches so many other lives. When he isn’t around, he leaves an awful hole, doesn’t he?”

George sees not only how the course of the universe would have been altered, but how important he is to the prosperity of home, as well. He wanted to leave Bedford Falls. “I’m gonna shake the dust of this crummy little town off my feet, and I’m gonna see the world,” so he tells future wife, Mary (Donna Reed). But a duty to his father’s legacy and to a family of his own redirects the course of his destiny. Dreams of college and exploring the globe, of Baghdad and Samarkand, are dashed. It’s a brutal blow, and a necessary one. Sometimes, we need to trip on shattered glass in order to be set on the right path.

Image courtesy of staticflickr.com

I am at the age where I must weigh the pros and cons of my own dreams. This morning I received a rejection to a short story. No problem. I shrugged it off. I get lots of those. Nonetheless, a voice murmurs within me that perhaps I am not meant to be a star writer. When we dream, we dream big. That’s why it’s called a dream. The chance of a dream becoming reality isn’t ludicrous when we see it has happened to our peers. A guy who had left the Cornell University writing program a year before I entered now has the Pulitzer, while a colleague got a major agent and a Norton imprint on his novel binding upon graduation, and another has become the buzz in the industry with her six-figure book deals. “You’re next,” one of my mentors told me. That was 15 years ago. I might not be on the wrong path, but perhaps this path I am on leads to a destination contrary to what I have been dreaming.

Similar thoughts apply to home. Growing up in Asia, I considered a vacation during summer break from school to be one spent across the Pacific, in either the United States or Europe, far from my culture and country of residence, and through my twenties and early thirties, with San Francisco now my address, family visits were more a chore than a delight. I sought independence, aimed for the moon. As it does for George Bailey, splendor awaited me in the unknown distant. I had to get it on my own because in dreams, we are self-absorbed and unstoppable.

Image courtesy of blogspot.com

George tells Mary that he’d lasso her the moon. “I’ll take it,” she says. Question is, what would she do with the moon? Ever the quixotic, George has the answer: “Then you could swallow it, and it’ll all dissolve, see. And the moonbeams will shoot out of your fingers and your toes and the ends of your hair.” He does lasso Mary the moon, but not in the form of Manhattan, Bermuda, champagne, and caviar. He gives her a home in a tumble-down grand house that together they restore, children, and an upright citizen of a husband whom had he never existed, she would have been a spinster entombed in a library.

It’s a wonderful life, George realizes in the end; a person can be great by doing small things. So Clarence earns his wings. As for me, I more appreciate my parents and siblings the older I grow, and I understand more clearly that the blessings that have graced me would never have been if not for them. “Be thankful you’re able to come home to the Philippines and just sit and do nothing,” my sister once told me when I complained of boredom during a visit. “Not everybody has that luxury.” Saying goodbye becomes more difficult each year, for time is fleeting, and gone are the days of youth and the notion of forever that comes with it. Exhaustion and disappointment have tainted my dreams. I’m not entirely sure anymore of the future.

Image courtesy of scriptshadow.net

Still, I believe an angel does watch over me. In moments of doubt, it flutters its wings to remind me that my life is not in vain. For writing is a craft that seasons with age, I’ve got stories in me that have yet to happen, more lives to touch, a chest of riches to share with all. Whatever my qualms, I can be sure of this: the strength of faith and family that has guided me thus far will allow me to prevail, be it through one tiny step after another.