Image courtesy of farm7.staticflickr.com

She hated June, the month that marks the beginning of the monsoon storms, because thunder and lightning terrified her.

“It’s like an earthquake but upside down, with heaven rumbling and splitting open,” Marissa once said.

I was seven. She was ten.

“I guess,” I said.

I had awoken to pee. Midnight had struck to a thunderclap, and the light was on. It emanated from a ceiling lamp bubble round, brightening an azure carpet and casting amid the drone of the air conditioner, in the stillness of the room, a memorial somberness to posters of Charlie Chaplin and Bruce Lee that hung above my bed. To my left, Marissa lay with the back of her head to me, deaf to my whining. There wasn’t space for two, and though I motioned with a push of my hands to budge her, I didn’t dare do so. That would have been akin to starting a fight with an older sibling, which our parents had reprimanded me was a no no.

“Be quiet,” Marissa said at last then turned to me. She had not been asleep at all. “What’s your problem?”

“You. Why are you here?”

“Too much noise outside, and it’s too dark.”

“I’m closing the light,” I said.

My sister sat up. “You mean turning off the light. You open and close a door, the refrigerator, an object. You turn on and off anything with a switch. Daddy keeps telling you that. And no, you are not.”

I stood to use the bathroom.

She laughed. “You always wear big shirts.”

“What?”

“You and your big shirts.”

“They’re comfortable.”

“You just want to pretend you’re wearing a dress.”

“No.”

“Yes,” she said. “And what’s with the colors?”

I was wearing a red Thai dye with the hem down to my thighs. Among my other pajamas were Thai dyes purple, orange, and green – a psychedelic array of what resembled thorn crowns flattened between a pair of glass panes then painted in joy. I didn’t have blue. Blue was a color our father forced on me. If I could have had my choice, my carpet would have been pink, and if Marissa could have had hers, her carpet would have been azure, pink being a color our mother forced on her.

Marissa wasn’t laughing anymore, though she did have a smirk.

What a weirdo, I thought.

Image courtesy of pinimg.com

Even during the day, Marissa spent more time in my room than in her own. She had an affinity for guy stuff. The Bruce Lee poster had been her choice – a print of the actor’s mug in black against a yellow backdrop, a don’t-mess-with-me austerity to the eyes. The poster was among my possessions because I had done my sister a favor by telling our father I wanted it. We were at a book store and there Bruce Lee was. Had she asked the poster for herself, our mother would not have consented; it wasn’t fit décor for a girl. Our mother, however, did allow Marissa one indulgence, that she could have a helmet cut similar to Lee’s, and this so that she wouldn’t be stifled by the heat. I got one, too. Regardless, we didn’t look alike. While my face was rice cake rotund on account of my weight, Marissa’s was narrow. The cut on me resembled a coconut husk. On her, she really did channel the martial artist.

Marissa grabbed me by the wrist. “Angelo, you are not turning off the light.”

“I need to pee.”

“You probably sit like a girl.”

“What are you talking about?”

She let go of me. “I don’t care. It’s Daddy who does.”

“Well, you stand.”

“I did once. Sitting is easier. But I’m a real girl.”

Marissa and I each had our own bathroom, and mine was bluer than my bedroom. The moment I stepped in, I felt as though I was standing at the bottom of an aquarium. I raised my shirt the way I had seen our mother raise her skirt, oh so gingerly with fingertips on the hem.

My sister was right. I sat. As I unloaded, I wondered how many hours more till sunrise, of squeezing into a bed made for one, dreaded what more of my habits Marissa would claim to be aware of. Though the sing-song cadence of her voice echoed in my ears, she was difficult to visualize. As with an infant, her features were non-descript. The most one could say about Marissa was that her eyes, nose, and mouth were well proportioned. (The same could not be said about me. My ears protrude as trumpet funnels.) Had it not been for the earrings – silver loops the size of a miniature clock wheel – Marissa could have passed as a boy. What a feat of evolution it was when years later, while earning an art history degree in New York, she would appear on the cover of a magazine, her hair permed and blow dried and sprayed into a voluminous do the fad of the 1980s, and in the decade after, what photographers found gorgeous in her would adapt a nobility when she lost her follicles, her eyes serene with courage that each day could be her last.

The shower faucet leaked. A puddle formed around the drain. Every tap of a drop sounded as the tick-tock of a clock. Amid the hue of ocean blue, a pair of towels hung in front of me, each adorned with a rooster as vibrant as tropical fruits.

Why my fondness of colors? I didn’t have an answer because I never thought about it. Maybe I favored neon as an antidote to Marissa’s penchant for starkness, which is what had attracted her to the Bruce Lee poster. Charlie Chaplin was my choice. The guy made us laugh along with TV features of The Three Stooges. Juxtaposed with Lee, he was a treat of gummy balls. The smudge of a mustache that followed the upward curl of his lips, the church dome hat, the floppy shoes and pants so large that they seemed about to slip down at any moment… to my young mind, the Tramp was cultivating the message that no matter how crestfallen we are, a smile is never too far.

Image courtesy of csrskabul.com

Charlie Chaplin was supposed to hang above Marissa’s bed. Marissa had said no. She didn’t want anything on her walls. She preferred 3,000- piece jigsaw puzzles. The puzzle images ranged from the Tower of London to a 17th century world map, from the Manhattan skyline to cherry blossom reflections on a lake. They strewed her room like painted carvings on floor tiles, providing visuals to lands and epochs that tickled her curiosity, she who was so restless that our parents allowed her swimming lessons along with ballet, high energy activities. She would eventually insist on college in the U.S., the opportunity to be her own person since a global education was the reason our parents had enrolled us since kindergarten at the International School Manila.

I reclaimed my side of the bed.

“I like blue,” she said.

I shut my eyes. The effulgence of the ceiling lamp created an incandescent spot on a black screen. “You’re scared of the dark.” I said, “and of being alone.”

“Yes, and I like blue. That’s why I want the lights on. Always. Mommy never stops about pink – pink curtains, pink rug, pink bed cover. I like sleeping to blue just as you like to wear big shirts so that you could pretend you’re wearing a dress”

“Shut up already.”

She did, though not for long. “It’s like an earthquake, but upside down, with heaven rumbling and splitting open.”

“What do you mean?”

I opened my eyes. I was the one who was supposed to be spooked over the clashing in the ether, God’s ire. During Holy Week, Marissa and I had watched a silent film on TV that depicted the Great Flood. The image of Noah with arms raised, his hair and robe awhirl in a cyclone, his foothold on the ark deck so precarious that a gale could have tossed him into the infinite horizon, haunted me for days. The drumfires from above and rain that struck our roof with the rattle of brimstones was what I imagined Noah must have heard. That my sister would find solace in her little brother’s bed made me wonder why her fear. I would have expected Marissa to excite over the world awash in a torrent. She belonged in water. In our backyard pool, whether exercising her freestyle or her backstroke, she swam with the grace of a ballerina, Tchaikovsky’s swan in flight across blue ripples, the splashes gentle, almost silent. Our father liked to tease her that she was Olive Oyle… so thin was she and gangly her limbs… but in water, she truly was a sight to behold.

“When there’s a typhoon, that’s what it’s like.” Marissa turned her back to me once more. “Just think, when you fall into the earth or are carried away, far away up there, you’re never coming back. Hurricanes and tornadoes can do that, you know.”

“That happens outside. Inside, we’re safe.”

“Outside. Inside. Doesn’t matter. A house can be lifted away.”

“I guess.”

Another thunder, God cracking His knuckles.

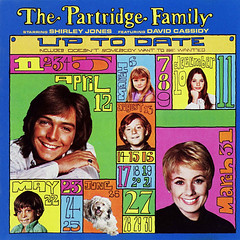

“Ba, ba, ba, ba, ba, ba, ba, ba, ba… “ Marissa broke out in song. The Partridge Family, of course. She had a crush on David Cassidy, he a hippy youth with long tresses and a cheerleader smile. Apparently, I wasn’t enough of a comfort. She needed some guy who fit the bill of a girl more than she. “I think I love you. I think I love you. So what am I afraid of? I’m afraid that I’m not sure of a love there is no cure for.”

“I’m closing the light,” I said.

II

Image courtesy of cache.osta.ee

Of all the memories we shared, this is the first that often comes to me on moments I happen to stare into space, be it on the subway or at the office, a corner room cluttered with binders and stationery and where I generate fundraising letters for a K-8 school in San Francisco. For the entire duration I’ve been at this job, the wall pad before me has been bare save for plastic knob tacks and phone numbers. A calendar of Oscar winning films is at present the one item that gives credence to an existence apart from what I’m paid to do.

For this month of September, a watercolor poster of “Casablanca” has Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman cheek to cheek. His brow is wrinkled. An expression of surrender softens his eyes. His face is long and mopey. She radiates trust and confidence in lips parted as if to whisper eternal devotion. Blonde waves highlight a complexion that exudes an after rain freshness. “It doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world,” so goes Rick’s famous goodbye to Ilsa. As the moral artillery in her husband Victor’s fight against the Nazis, she must sacrifice the happiness she could have experienced with another man. Such is love.

Beneath the calendar, sunshine through my window frames in a glow credit card forms piled on my desk. The pavement outside is sand dune pristine, pedestrians on them scarce as are the cars that drive by, and a garage door to a house across the street glimmers with the promise of light on a projection screen. This calmness that is Pacific Heights creates the ideal neighborhood for kids: tomorrow poses no threat, while each day relegated to yesterday is one banana more that a child has consumed with one’s morning cereal, sweet and nourishing, a memory to relish.

My supervisor is out. I’ve got no pressing project. That it’s already autumn has a dual effect on me. I mourn summer, and I am also amused that in the Philippines, in another time, September was a reason for bliss; September was Marissa’s favorite month. Until it arrived, we had to endure gusty weeks. Most kids dread September, the start of the school year. Not Marissa. She equated her first step into a new classroom to the awakening of cicadas that in the monsoon had been dormant.

That’s one thing I miss – the chorus of cicadas, their chirps escalating to a crescendo as to harken the late hours, twilight’s chromium luster. Nevertheless, I choose to be here in the U.S., and the Dover School can offer its own treasures, bromidic as they may be. Take now. A teacher is reprimanding two girls in front of my open door for pushing in line. Past a file cabinet beside which a pizza box balances atop a recycle bin, the girls stand sleek in leotards and ponytails. They are far from adolescents yet already in possession of an adolescent spunkiness; neither wants to admit to having initiated the shoving. Mr. O’Farrell glances at me. A patient figure in a lumberjack shirt and a beard the density of a bird’s nest, he strains from rolling his eyes across his forehead. Down the corridor, fifth graders in a music class sing “This Land Is Your Land” to the jaunty accompaniment of a piano.

Such a familiar moment, this co-mingling of melody and infantile discordance, no matter the difference in people and place and the distance of everything.

III

Image courtesy of media.gettyimages.com

“Little kisses,” Marissa said during a weekend swim.

She stopped in the middle of the pool and raised her face to the sky. Earlier, she had exasperated us with her continuous record playing of the Partridge Family. The record was new and so was the player, a red and white portable box with a headshell fashioned after a doll’s hairbrush. “Marissa, why don’t you turn that off for a while,” our father had said in a manner both gentle and emphatic. Such is our father’s tenor that even when he whispers, he’s got volume.

My sister obeyed. As a reward, our father permitted her a swim. The June when she had snuck into my bed had passed. July brought us on our annual trip to the U.S., where through August, we boarded planes to visit relatives in four different states. Classes were to commence on Tuesday. September was here. The grass in the resurgence of the sun had an emerald shimmer, and if it did rain, then it was sporadic, a caress compared to the punch of a typhoon.

Marissa had been in the pool for half an hour when a cloud rolled forth, immersing in shadow the surrounding trees, the leaves grown to such opulence that they appeared to be a bundle of green birds. Pinprick indentations mapped the pool. Rings formed around them, liquid halos, then disappeared as quickly as the next drop.

“Little kisses,” she yelled.

Since I didn’t know what she meant, I put on my trunks to find out. I was with our mother, who urged Marissa from the back lanai to get out before the drizzle strengthened. Downpour aside, our mother wasn’t keen on Marissa’s spending much time outdoors. A tan to her is synonymous with the province, with farmers and rice planters – laborers. We are city folks. All my life, other people have fixed our beds, washed our dishes, and taken out our trash. Our mother allowed me to dive in only because I had the power to cajole Marissa into the house.

“Five minutes,” our mother said to me, “then you tell your ate enough,” Ate being the respectful epithet for big sister.

Our mother was dressed for the humidity – spaghetti straps, a sash that accentuated a tiny waist, and baubles to compliment a neck fair and smooth as those of an actress in old movies. She watched us from the back lanai, in a chair with a cushion that bore a daisy motif. She adores flowers, our mother does. Rattan baskets and porcelain from Japan and China decked our home. Lobster claw plants, lilies, and tree branches filled them all. One arrangement had a marble-sized fruit we call kalamansi, our native lime, ready for the picking.

Image courtesy of pinimg.com

The lanai threshold was circular. Screen doors opened into the garden, to the pool yards away. Our mother sat at the center of the entrance, an empress austerity to her with back straight and head high.

My sister was right about another thing. Rain on the face is similar to a kiss multiplied by ten, a hundred, a thousand. I knew about kisses from our mother. As for Marissa, where she got the analogy beat me. I’ve never seen our mother kiss her. Our father did hug her plenty. Whatever lip pecks were involved was largely on her part. I opened my mouth to feel the patter on my tongue.

“Rain has taste,” I said. “It’s not bitter likes tears. It’s sweet.”

“It’s tasteless,” said Marissa.

“It feels sweet.”

“Sweet is a taste, not a feeling.”

“Then what it is I feel?”

Marissa gave me a sideward glance. “You’re feeling good.”

Marissa’s bathing suit was a one-piece patterned with Lifesaver stripes. She resembled a cluster of candies in a slot machine afloat on water. And she was caramel brown. None of us have ever had that hue. My yellow trunks emphasized my paleness. Plus, my tummy looked balloon inflated. No wonder our mother had a habit of pinching my cheeks and teasing me that I was delicious enough to eat. I was a dish of almond jelly and egg custard in boy form.

“I’m supposed to tell you to go in,” I said.

“I know,” Marissa said.

“Why don’t you listen to her?”

“I will.”

“When?”

“When I feel like it.”

A spurt of sun broke through the grayness. A rainbow arched over our house, a two-level abode that boasted a stucco facade and a navy-tile roof, ionic columns to a balcony balustrade and air-conditioners that protruded from windows. In the lanai, our mother sat cross-legged, hands on her lap, as to strike a pose. Our eyes met. She nodded in that commanding way of hers… I was designated to do a job and do it I must… but I shared Marissa’s sentiment. The moment was too lovely to let slip away.

Neither did our father share our mother’s anxiousness. In khakis and a golf shirt, black hair pomaded and combed high leading man style, he appeared in the lanai, a red toolbox in one hand and a drill in the other. He set them on a glass table behind our mother before he disappeared again, only to reappear with a painting, an oil that depicted a man and a woman astride a carabao – our indigenous buffalo – he in a straw hat, she in a head scarf and a white top flimsy as onion thin paper. Both were in a landscape of oscillating stalks and orange-rimmed clouds. Our father thrilled in weekends where he could engage in domestic chores. If he weren’t polishing one of the wall-length screens our mother had purchased in Hong Kong – antique gems on which were imbedded soap stone carvings of peonies, bamboo, and members of the imperial court – then he’d be hanging art.

What a mystery rain is. What a mystery Marissa is. 40 years later, I still can’t figure her out. She had been tiger tough on the exterior yet kitten scared inside three months earlier, hiding underneath my sheets upon the first typhoon of the season. On this afternoon, she outstretched her arms and neck as if she were offering herself to God’s tears.

“Maybe snow is as sweet as rain,” I said.

“Sugar balls,” she said.

“Next time we go to the States, we should go where there’s snow.”

“Yes.”

Image courtesy of farm8.static.flickr.com

By virtue of our education at the International School Manila, America intrigued us. The academic calendar at ISM coincides with that of the States, while summer for local schools fall in the months of March to May, when temperatures soar to the 90s. The heat scalds to such a degree that we would sweat the second we’d step out of a cold shower. To parallel an American education, our parents gave us an American summer: McDonald’s French fries, Hershey’s chocolate, and the very American invention of the mall.

Although we had been traveling to the U.S. ever since I was born, the trip from which we had just returned was the first to awaken in me the possibility of claiming as my own this other country. An aunt and uncle live in Cleveland, in a white house with a trio of dormer windows that rise from a black roof, on a street populated by houses of the same design. Back then, they drove a station wagon, and with our cousins, they would take Marissa and me to May Company, a department store that was a smorgasbord of Hallmark greeting cards, Betsy Clark stationery, lego, and all sorts of products dazzling to the eye – from shampoo bottles the multitude of colors in a Crayola box to plastic chairs as sumptuous as cherries and grapes, from glow-in-the-dark surfer shorts to bubble gum in wrapping the shades of Jupiter. As a souvenir, our parents bought her the record player and the Partridge Family album; I got a Superman watch and a pencil case to match.

“Okay.” Our mother stood from her chair in the lanai. She waved her arm in a come in gesture to Marissa and me. “That’s enough.”

The drizzle remained constant. It neither hardened into a barrage nor lessened into taps. A ray of light continued to pierce through a murky cloud. The world had stopped on its axis.

This time Marissa complied. Because she did, so did I.

“Why can’t you listen to me?” our mother asked.

“I’m here,” said my sister.

“Did you have to make me wait and repeat myself?”

“I’m here.”

Marissa was catching up in height to our mother, who stood at five feet but appeared taller on account of heels and her carriage. In a few years, my sister would surpass our mother in physical stature, reaching a full height of 5’6”, and the two would share an affinity for make-up and fashion, a commonality that would cause our mother to boast of her daughter’s New York move, “That city is good for her. When she walks down the streets, men strain their necks to look at her and can’t turn away. Also, she’s at Barnard College.” I might have already noticed on that afternoon the beauty Marissa would someday burgeon into. She held up her chin with the pride our mother did hers, and in her profile a delicacy marked the curvature of her lips and shoulders. Just as our mother refused to buckle, so did Marissa.

“You should have been here way before now,” our mother said, “dried up, showered, and fresh. Look at you. You’re wetting the floor.”

“You’re so bossy, Mommy.”

Our father, nail in hand against the wall where he was to hang the painting, turned to my sister. His eyes were incensed with the fury of a volcano about to erupt. “Maria Clarissa, do not answer back at your mother.”

Image courtesy of pinimg.com

“You said I could swim.”

“That doesn’t matter.” His voice reverberated in the lanai a blast of harshly articulated words. “When your mother tells you to do something, you do it.”

Marissa was mute. To our mother, she always had a response, whereas our father had never given her a cause for one. This was the only time I ever witnessed her chest cave in.

“A typhoon can slam any minute. Never mind that it’s September. It’s not safe out there,” he said and then, “Angelo, hand me the drill.”

The drill was on the glass table in front of the wall where stood our father. He extended his arm towards me. I suppose he had intended to ask our mother for the thing, but since I was present, he resorted to me. Sopping wet as my sister, I created a trail of water footprints on the floor from the threshold to the table. The drill was a gray instrument that replicated a gun. It had a massive grip, a trigger, and a drill bit that extended from a barrel. I imagined the device in operation, the screeching noise and the drill bit in furious rotation, digging mercilessly into a surface, debris spewing all over.

“Angelo,” our father said, rage still in his eyes.

No sooner had I picked up the drill when it slipped. A bang resounded. A bullet hole crack formed on the spot where it landed.

Our father did not budge. His arm remained extended towards me.

“You’re supposed to pick it up with a firm hold, not a limp wrist,” said our father.

Betsy Clark, the Partridge Family, and a Wonder Woman watch… that was the Superhero I was crazy about, Wonder Woman. There was something else about America that made me wish I were back there at that instant, something more.

“This is how you do it,” our father said. He grabbed the drill as if to crush it; so red were his fingers from the pressure. “Now you.”

In May Company’s jewelry department, as our mother gazed at herself in a counter mirror to consider for purchase a gold necklace, two men stood beside her. They were spruced up in denims, suede vests, and cowboy hats. They each had a Marlboro man mustache and that hyper male squint. The pair could have been twins. Then again, not quite. The aura about them transcended the familial. They were too close, in a shared personal space. One man placed a ring on his finger then raised his hand to admire it, after which he took it off and put it on his companion. I had never seen such intimacy between two men.

I think I love you. I think I love you. So what am I afraid of? I’m afraid that I’m not sure of a love there is no cure for.

‘“Grip harder… Again… Grip the way a man does… Again…”

“My wrist isn’t limp.”

“Again.”

“That’s enough, Elpidio,” our mother said.

The kitchen door swung open. The door was located in the dining area that led to the lanai. Our wash lady came from the maids’ quarter downstairs, holding up on a hanger a dress with seashell patterns.

Our mother continued on with my sister. “You are wearing that tonight.”

IV

Image courtesy of fotodicasbrasil.com.br

A photo of me in the Superman watch and Marissa in the dress is on Facebook. She stands toes pointed inward at the foot of the stairs that lead to the second floor bedrooms. I am to her left. I have placed my hand on the handrail with the top of my wrist turned to the camera to show off the red and blue caped figure. The steps are varnished narra. The baluster is brass and metal coiled to form an ascending line of arabesque patterns. Such dexterity merits the proper attire. Our mother had a seamstress sew Marissa’s frock, while my outfit, a rust polyester leisure suit with bellbottoms, was tailor made.

The photo makes me chuckle. Kids walk to and fro in the corridor outside my office. The girls are dressed as if they are off to a pilates class. The boys are in basketball shorts. At any given school in the Philippines, athletic gear is exclusive to physical ed. Leave it to Facebook to punctuate the disparity between the students at the Dover School and me. My chuckle far exceeds this, however.

For our father, one shot is never enough. He takes at least three. That afternoon 40 years ago, he had one of the maids take several pictures of the four of us.

“Excited?” he asked as he put an arm around my shoulders.

“For what?” I replied.

Our father has always been a dapper figure in slacks without a crinkle and button down shirts that accentuated arms muscular from a youth of bricklaying – a package that exuded a confidence in him for having risen in social rank from laborer to owner of a construction company. As a victory laurel, he had won the admiration of a Manila socialite. I saw at that moment the impact our mother must have had on our father when he had first opened the door for her as she stepped out of a car and onto the lot where he was overseeing the building of a bank for her own father, a financier, one of the Philippines’ most notable. Holding Marissa to her bosom, our mother was prettied up in pearls and a blouse that rippled to her every movement – a raise of the arm as she instructed the maid on the camera button to click, a sway of the hips – and as she tilted her head to a quarter angle, I noticed that Marissa herself was in awe. She gazed up at our mother, straightened her stance, and positioned her toes forward. In an instant, the seashell dress that had been an awkward fit, one cut in the pattern of a nurse’s uniform, was awkward no more.

“For dinner. You kids said you wanted to go out tonight, so we’re taking you out. You wanted Italian food, so we’re having Italian.”

Whether or not the rain persisted, I don’t remember. It doesn’t matter. Our father had promised us a treat, and he has never rescinded on a promise. The events of the afternoon were behind us. Not only had I picked up the drill with a firm hold, but I had also hammered a nail into the wall, and this on my own initiative rather than on our father’s prodding. I pounded the peg with such force so that, upon the slamming of steel against steel, I was the loudest person in the lanai.

Image courtesy of fc07.deviantart.net

These photos had been set aside, buried for nearly four decades in magnetic pages stacked in a bureau and melted from the tropical heat, forgotten. The memories might have faded for good if not for digital restoration. They now jump out from the computer screen in front of me as if I am spying through a window.

I ponder how Marissa would have adapted to the internet era. She might have been keen on streaming the pop songs we grew up to, but she would not have been a Facebook fan. Remembrances of her gauche girlhood made her blush, what more that they are currently accessible at the click of a button. I complement my own boyhood pictures with selfies that show off a six-pack gained from my latest workout regimen. More importantly, Facebook connects me to our parents, who delight in showing the world that one has managed to retain an unblemished complexion and the other plays nine holes every weekend, grayness on her part and a gut on his notwithstanding.

What truly perks up our parents is the chance to post the trove of family pictures, their way of immortalizing our yesterday. They sold the house years ago. With Marissa gone and myself settled in San Francisco, they had no reason to hold on to such an enormous dwelling. Our parents today live in a condo at Fort Bonifacio, a military base turned into commercial real estate to accommodate Manila’s population influx.

Besides, I am now the lone child who visits. When I was in college at Berkeley and Marissa managed an art gallery in SoHo, the house anchored us both to our existence across the Pacific, luring us back every vacation, our rooms unchanged – mine still blue, hers still pink – save for the installment of a central air conditioning system and her floor free of jigsaw puzzles. Or perhaps our parents’ release of the house had been imminent ever since Marissa graduated high school from ISM.

“You can leave the family?” I asked in consternation to her declaration that she was off to the U.S.

“Yes,” she said.

Our parents acquiesced. Their daughter deserved the riches of the seven continents… and much more. As a woman, Marissa would be a certified scuba diver. A dear thing she would leave me with is an album of photos she had taken of her sea excursions. Star shimmering corals, rocks as porous as the moon, midnight streaks on fish sun yellow… the deep was a galaxy she would claim her own, while above, the tug boat that had brought her far away from Palawan Island or the Malibu shore waited adrift, undulating on soft current, as if it were an airship parked on a cloud.

Shortly after her 30th birthday, Marissa got married. His name is Bill. Rather than constricting her independence, Bill fostered it, teaching her to windsurf and goading her to join him on a 21-kilometer run at Angkor Wat, the cone towers gilded in the first blush of a new morn. Bill is an engineer and handsome in an all-American way – eyes the blue of Lake Placid and a jaw Mount Rushmore chiseled – yet whose neck and overbite conjure the vision of a giraffe.

“He’s not one to easily blend into a crowd,” Marissa said over the phone on the day he proposed. “How can I say no?”

And stand out Bill did, all 6’3” of him, in a black tux and a silver bow tie, his arm ornament my sister in a lace gown that in the sunshine permeating the church scintillated on her like diamonds on white petals. The open portals, bronze statues of saints encased in each, and the brightness of day through stained glass windows that could have been crafted from sapphires and rubies created a feel of space. Surrounding arches diminished Bill and Marissa to the size of a man and a woman on a wedding cake. They took their vows before an altar as majestic as a piece of the Parthenon, and in the midst of light particles that danced to the vaulted ceiling, they seemed ready to take flight.

But Marissa would have to fly alone. A year later, surrounded by bare walls, wisps of heaven outside a window would waft into her room. She had done what could be done. Treatments both medical and holistic could no longer combat the inevitable.

“If only it had been detected earlier,” our mother would bemoan.

“Stop, Mommy” Marissa said. “This is the way it is.”

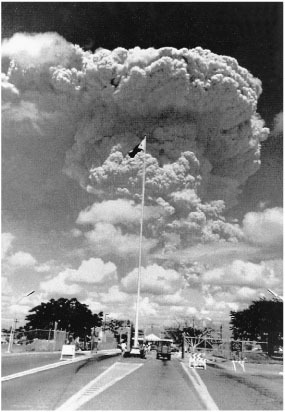

Image courtesy of scienceclarified.com

My sister did have one regret, that she would not be able to visit Manila just once more. Instead, we gathered at her bedside as the TV featured footage of the latest happening in the Philippines: the eruption of Mount Pinatubo. A tsunami of volcano ash surged over stalks and palm trees. Nearby villagers coated in dust meandered on dirt roads as if the petrified corpses in Vesuvius had themselves been resurrected. The death toll of 722, a statistic that included casualties brought on by subsequent diseases and typhoons, flashed onscreen.

“The things I used to be scared of, so silly,” Marissa said. “There are worse things that happen. Even then, once it’s over, it is over.”

The month was June, on a blistering day in New York. No personal mementos occupied the night table. Marissa didn’t want any past present, only the future, which for her was represented by a medallion that bore a relief of the Pieta, and orchids, flowers she favored on account of their simplicity. She always had a sharp bone structure, but instead of rendering her face sallow, the weight and hair loss accented the sculptural quality of her features. And how soft her hands were as she rested them on her lap, two doves in repose.

“Are you sure you want to watch this?” Bill asked. He sat beside her, on the edge of the bed, almost ready to climb in.

“It’s nearly done. After this, ‘The Simpsons’ is on. We can all laugh.”

“Laugh?”

“Yes, Bill. Laugh.”

Marissa grinned at him the way she had at me the June she had first snuck into my bed. “I hate that shirt,” she said.

“That’s why I’m wearing it.” Bill had on a tee with an image of Bruce Springsteen’s jean-clad derriere against a background of red and white stripes. A red kerchief hung out of a right hip pocket, and a coffee stain blotted the center. “If you want to laugh, check out Bruce’s butt.”

“You’re such a hick.”

“So I am, but… honey… a natural disaster?”

“Oh, that shirt is so ugly.”

Our mother paced about as she talked of placing a vase here and hanging a watercolor there. “A picture of a teapot would be calming. Of roses, too.” She had been speaking of livening up the room for the two weeks since Marissa had been there. Our mother’s suit was tangerine. Two-toned pumps matched a purse. Buoyed by Marissa’s daily compliments over a purchase, she spent hours on Madison Avenue when out of the hospital. Her daughter would be in heels soon enough, it seemed.

“She’s a minimalist,” our father said to honor my sister’s wish of a stark room. He stood with arms folded, his big boss stance. Our father’s shirt was pink linen with a Mandarin collar. The shirt had been my choice, while my own shirt was blue, also my choice. I was glad to keep our mother company at Barneys, and I had come to appreciate blue as much as our father did pink. The color complimented his whitening hair.

Me, I was a mute figure in a chair. I sided with Bill. Marissa’s insistence on news of a cataclysm on the par of Armageddon was weird. But who were we to change the channel? We were her visitors.

V

Image courtesy of pandoraoutlets.ius

The Dover School is fundraising for an innovation lab, a physical space where students with tools that range from a pencil to a hammer can design and execute projects that encourage trial and error and learning through failure: a velocipede, a telescope, a thermometer… As Marissa’s jigsaw puzzles did for her, the pertinacity to complete a whole can inspire these kids to dream, not only for themselves, but also for others. Marissa herself once envisioned that our father would erect a building higher than the clouds, a monument of a home.

“Maybe typhoons won’t be scary up there,” she said on that rainy night our father treated us to Italian food. “We’d be above the mess down here. When the sky clears, we’d have a view of everything. Every mountain. Every valley. Every rooftop. Everything.”

I was gorging on my pizza. A lit candle on our table flickered shadows on Marissa’s lasagna, and in the soft light, with her before a reef tinted wall, silver threads to the seashells on her dress sparkled as if she were a creature of the deep.

“Everything,” I repeated.

The word would resound in my head in the midst of what our father dubbed her “minimalist” surrounding. For all we accumulate since birth, we leave with nothing, not even laughter. No wonder hospitals are frightful. Rooms possess the desolation of a jail cell.

Screw “The Simpsons.”

“No,” I wanted to block the TV and declare as if I were some soap character that had popped out of the screen. “Things don’t end just like that. The rest of us go on living. Small as we are, our loss is as big as today’s headlines. Tomorrow needs to hurry, so I can get on with this business of starting again. I’ve still got my dreams.”

Instead, I sat through the shenanigans of America’s most beloved family as the flames of a setting sun made way for stars and my stomach growled for a roast chicken.

Nobody laughed. Rooted to Marissa’s side by the window, Bill flashed some teeth. That was all. I was with our parents on the other side, the door behind us. They were seated now. Our chairs were foam padded and covered in cream upholstery, fluffy to the touch and celestial to behold so that along with the numbness of the moment, we could have been floating in air. Bill turned off the TV. The room fell silent. All those around me looked old, weary, their faces furrowed and eyes damp, as if everyone had forgotten what is to be.

Image courtesy of blog.jonolan.net

Except Marissa.

“Sweet September drizzle,” I whispered.

Marissa laid her head back.

“Lifesavers… Leaf wings… God’s kisses…”

So soft was her pillow that she seemed to sink into a cloud.

“I think I love you. I think I love you. So what am I afraid of? I’m afraid that I’m not sure of a love there is no cure for.”

Marissa shut her eyes.

Won’t you eat a chicken with me? I thought. What happens now?

If I could share with my sister the answer that life has provided over the years, here’s what I’d tell her:

Bill has remarried. Katrina is from Texas, born and raised, and of Mexican descent. The pairing of a Southern drawl with a swarthy face and eyes the black of melanite can be jarring, though only for the first few minutes that you meet her. She has a smile so infectious that you succumb to her warmth, and the way she says hello, you’d think you were the only human she cared to be with. They have a son, a lanky teen who wears his hair anime style, long so as to cover his ears and jaggedly cut. Lance is on his first year at New York University. He wants to be a scriptwriter, which is what Farley is.

Farley… such a dorky name, as is the man who owns it. He’s got a duck walk and a unibrow, black-rimmed glasses on a conical nose. He’s also able to unbolt the screws to a hubcap with one yank of a wrench, his forearms Popeye pumped; he makes the best paellas with jumbo shrimps and the spiciest chorizos; and his imagination has got Daddy and Mommy hooked on Netflix.

“Clever,” Daddy said of one film about an old farmer in the Idaho outback who with his dog, an Irish setter named Auburn, reunites a boy and his family and uncovers a drug ring. Mommy said it made her cry. “You must be proud of him,” she commented to me. “I am,” I said.

None of the films Farley writes would ever screen in the Philippines. He does indie work, not Hollywood big budgets, which are the only features that sell internationally. I love this auteur element about Farley… it shows an uncompromising disposition to be true to himself… and whatever it is he loves about me has kept us together for eight years. Today is our anniversary.

I can go on, but these are the important stuff. Goodbye for now.

The corridor outside my office is quiet. The students have been dismissed. The garage to the house across the street has dimmed, though it isn’t entirely blank. It never is. History makes us see things that aren’t there, our thoughts projected through a camera ensconced in our memories. I wonder what family today occupies our house from long ago, if at the moment a brother and his sister are bobbing in the pool, rain kisses on their cheeks amid liquid halos.

Image courtesy of images.pond5.com